The Talking House

Most of us experience buildings in a vignette form, coming and going past or through them and seeing them briefly from different perspectives. We see a thing — a door, a window, a wall, an architectural detail. But Burcin Becerik-Gerber sees more. She sees ideas.

Becerik-Gerber, an associate professor in the Sonny Astani Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at USC Viterbi, believes the spaces we inhabit will soon become intelligent enough to distinguish between family members and guests, and adapt to individual needs down to the rhythm of our heartbeats.

Her premise is simple but enticing: Humans beings are unpredictable, so why should our buildings be static and boring?

“Considering Americans spend 90 percent of their time indoors, buildings hold multifaceted significance in our everyday experiences,” Becerik-Gerber said. “But the majority of today’s buildings are designed with an emphasis on immediate form and function rather than operational flexibility. We envision built environments and their users to co-evolve as they interact with and know each other, learning to adjust to the unexpected.”

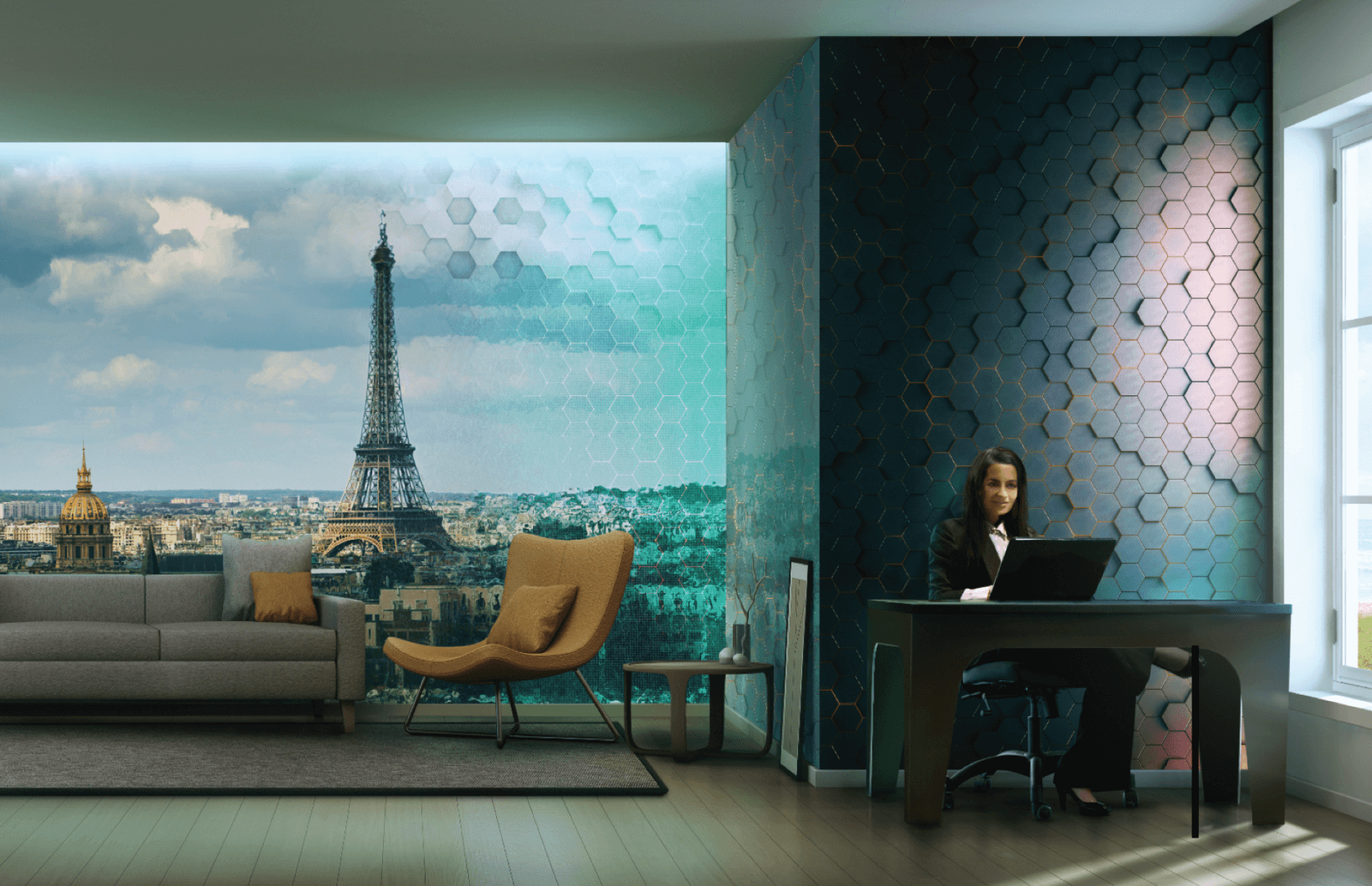

One of her research projects is an intelligent physical system that enables autonomous building skins, or façade systems. It’s not just a building’s outer shell — it’s a dynamic system that interacts with life in and out.

The “skin” senses building data, like room temperature, available natural light and plug loads, and couples it with occupant data such as comfort preferences and the frequency of interactions with building elements, all in real time. Becoming “smarter” as it learns about us over time, the building works to enrich the multisensory experience of its occupants.

An important research challenge is to design and model not only the spatial [office versus conference room] and temporal [summer versus winter], but to also understand and model the situational.

From the kitchen to the bedroom and from the bedroom to the backyard, the building would curate your experiences as you interact with its multiple data systems. Monet walls in the kitchen and Matisse in the halls? Switching wall panels!

As the building evolves to suit your needs, there will be some negotiation, of course. If you’re depressed, you probably shouldn’t be spending all your time in dark, stuffy interiors. The building would know that, as it would know your vital signs and whether to call for help in

an emergency.

Her team is now working to add flexibility to the façade systems by integrating technologies like electrochromic glass and adding real-time feedback to the building’s skin, which hasn’t been done before.

A building is not merely a building but a shared spatial experience that embodies and shapes our values — a living entity with a symbiotic relationship to its environment,” she says.

Becerik-Gerber has also teamed up with the global engineering firm ARUP to design a smart desk that uses unsupervised machine learning to autonomously adjust temperature and lighting and to power devices. It will independently detect changes in preferences over time, pulling from a knowledge base of your actions and sensing things such as skin blood flow through infrared thermography.

Becerik-Gerber thinks of all these ideas as a unique way of spatially envisioning the self.

Want to take an audio journey into this future? Listen to “KATE 2600,” a new episode of our podcast, Escape Velocity. Be our guest as we transport you to New Amsterdam — a futuristic city where buildings are not inanimate but sentient beings, uniquely programmed to suit residents’ needs.