Bionic Hands for War-Wounded Children

In Haiti, a small island beset by widespread poverty, violence and earthquakes, 20 percent of children will die before the age of 5. Countless others will bear the marks of survivors: missing hands, missing feet and other life-changing injuries that will never fully heal.

This is a story about a group of USC Viterbi engineers and a USC Dornsife premed student with a different kind of mission. A group of students bound and determined to restore the bodies of children rising from the ashes.

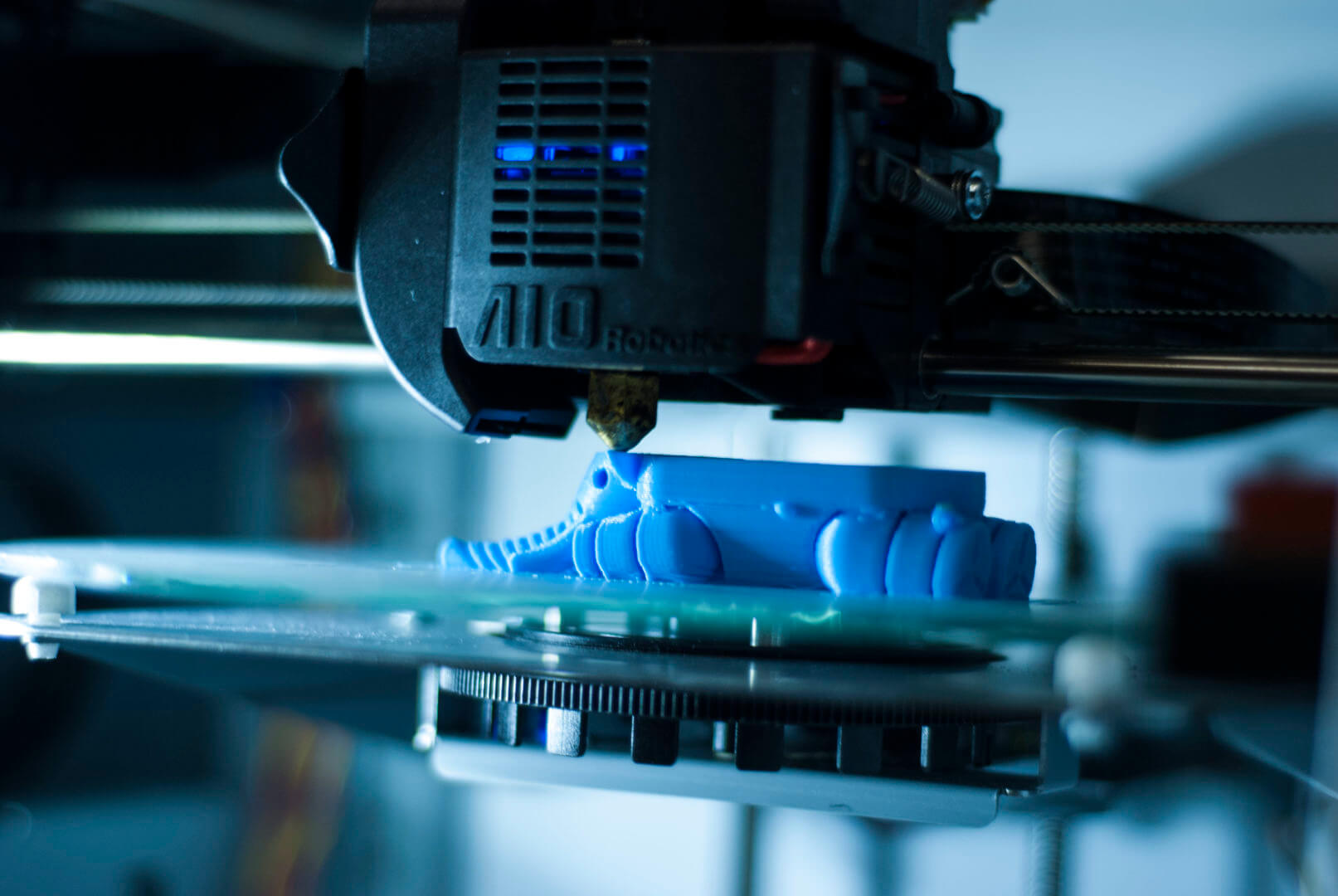

Alison Glazer, mechanical engineering senior and president of the student-run club 3D4E (3D For Everyone), had been tinkering with the power of 3-D printing for some time. She even built a 3-D printer herself, from wood.

But something wasn’t right, Glazer said: “It was a feeling of spinning in circles. We were printing cool toys, key chains and iPad holders, but we wanted to do more than what the average kindergartener could.”

Sitting in her lab, surrounded by 3-D printed toys and a 3-D printed head of the Greek god Zeus, propped like a trophy at her desk, Glazer pondered the limits of this technology.

“What if we could use the machines in a more meaningful way?” she wondered. “3-D printing with a purpose.” Little did she know that somewhere across the globe, in a very different lab, someone else was thinking the same thing.

Kara Tanaka, an accomplished sculptor and premed graduate of the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, was displaying her sculpture called “A Sad Bit of Fruit, Pickled in the Vinegar of Grief” at a solo exhibition in Reggio Emilia, Italy. Forged out of fiberglass, enamel, linen, steel, wood and anodized aluminum, the installation speaks of things lost and the disappearance of the human body, a theme that has strongly marked Tanaka’s artistic journey.

Kara Tanaka, an accomplished sculptor and premed graduate of the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, was displaying her sculpture called “A Sad Bit of Fruit, Pickled in the Vinegar of Grief” at a solo exhibition in Reggio Emilia, Italy. Forged out of fiberglass, enamel, linen, steel, wood and anodized aluminum, the installation speaks of things lost and the disappearance of the human body, a theme that has strongly marked Tanaka’s artistic journey.

She followed its thread into 3-D printing’s new niche — medicine. “When you print a hand for a child, you’re literally sculpting that child’s body, layer by layer,” Tanaka said. “It’s an emotional experience. You know someone’s life will be dramatically changed.”

Tanaka developed a relationship with e-Nable, a global network of volunteers that supplies 3-D printed hands to children around the world, on demand. She created the USC Freehand Project to supply e-Nable with as many hands for Haiti as possible. But the human hand is a wickedly complicated collection of bones and joints — the misalignment of one can throw life off balance. Tanaka realized she didn’t just need to make a hand; she needed to engineer one.

“I never hung out with engineers,” admitted Tanaka, “getting to know them and understand them was crucial to the project’s success. USC gave us a taste of what real-world medical breakthroughs are made of — doctors, engineers and artists working together to make the future happen.”

Glazer agreed: “Everything in our future is about collaboration. If it’s happening already at the professional level, starting early means we’re a step ahead of the game.”

For starters, the club received an order from e-Nable to create 12 to 15 hands of various sizes for Haiti. But their printers were sadly overworked and in need of repairs. They reached out to AIO Robotics, a startup out of the USC Viterbi Startup Garage, which donated its new Zeus model 3-D printers.

“Hands for Haiti” was such a success that last spring e-Nable approached 3D4E with an even bigger challenge: They wanted to send hands to the most dangerous part of the world right now — Syria, where the five-year-long war has claimed the lives of nearly 12,000 children. To help them do it, they recruited Baltimore area Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

“Hands for Haiti” was such a success that last spring e-Nable approached 3D4E with an even bigger challenge: They wanted to send hands to the most dangerous part of the world right now — Syria, where the five-year-long war has claimed the lives of nearly 12,000 children. To help them do it, they recruited Baltimore area Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

But there was a problem: Baltimore was on lockdown due to civil unrest following the death of Freddie Gray, who died in police custody. Mail wasn’t getting delivered, schools were on shutdown, and streets were unsafe.

They broke through a vicious snowstorm, rioting and arson, but when they finally arrived, the scouts were proud to earn their merit badges assembling these cool superhero hands for the children of Syria.

“It was a strong statement, and in many ways a quiet protest against hatred and violence, ” said Tanaka. “It fueled our creativity and desire to do more,” adds Glazer. After the Syria project wrapped, they didn’t throw a victory party. They did what good engineers do: They went back to the drawing board.

3D4E has a few projects in their imagination: creating a fully-functioning myoelectric arm, printing a 3-D map of USC campus, and creating a novel scanning system for capturing a full 3-D model of the human body. For now, they’re continuing to make hands, this time for the children of Sierra Leone.