The World’s Smallest Movie Studio

USC’s Translational Imaging Center is not Universal Studios. Yet, it produces some of the most remarkable motion pictures in science: watching an entire living brain, down to individual neurons, explore mathematics, form new memories, even sleep.

Scott Fraser, a physicist, developmental neurobiologist and biomedical engineer, and his team employ some of the most advanced filming techniques around to capture brain cells in conversation.

“It might be closer to the world’s smallest reality TV studio,” said Fraser. “There’s no script here. And no choreographed events.”

Here are some notes from the set:

Key Collaborators.

Fraser often works in partnership with Carl Kesselman, a USC Viterbi high-performance computing expert at the USC Information Sciences Institute, and Don Arnold, a USC Dornsife neuroscientist. He recently began hunting for a “mathematics gene” with Italian neuroscientist, Giorgio Vallortigara of the University of Trento and English geneticist, Caroline Brennan of Queen Mary University of London.

Stars.

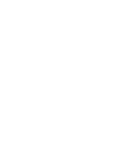

The zebra fish are like two week-old child stars with a special advantage: their transparent heads allow Fraser to see networks of brain cells light up like Christmas trees. Said Fraser: “Unlike a human brain, they’re just small enough to fit underneath a high-resolution microscope. But large enough to contain tens of thousands of neurons that are undergoing some of the same developmental events that take place in a human brain.”

Lights.

The filming needs just enough laser light to see individual zebra fish neurons – but not so much that it actually damages its tiny brain!

Said Fraser, “We use a variety of different lasers – we can use one color to see the shape of the neuron and yet another color to see the neuronal activity in the cells.”

Camera.

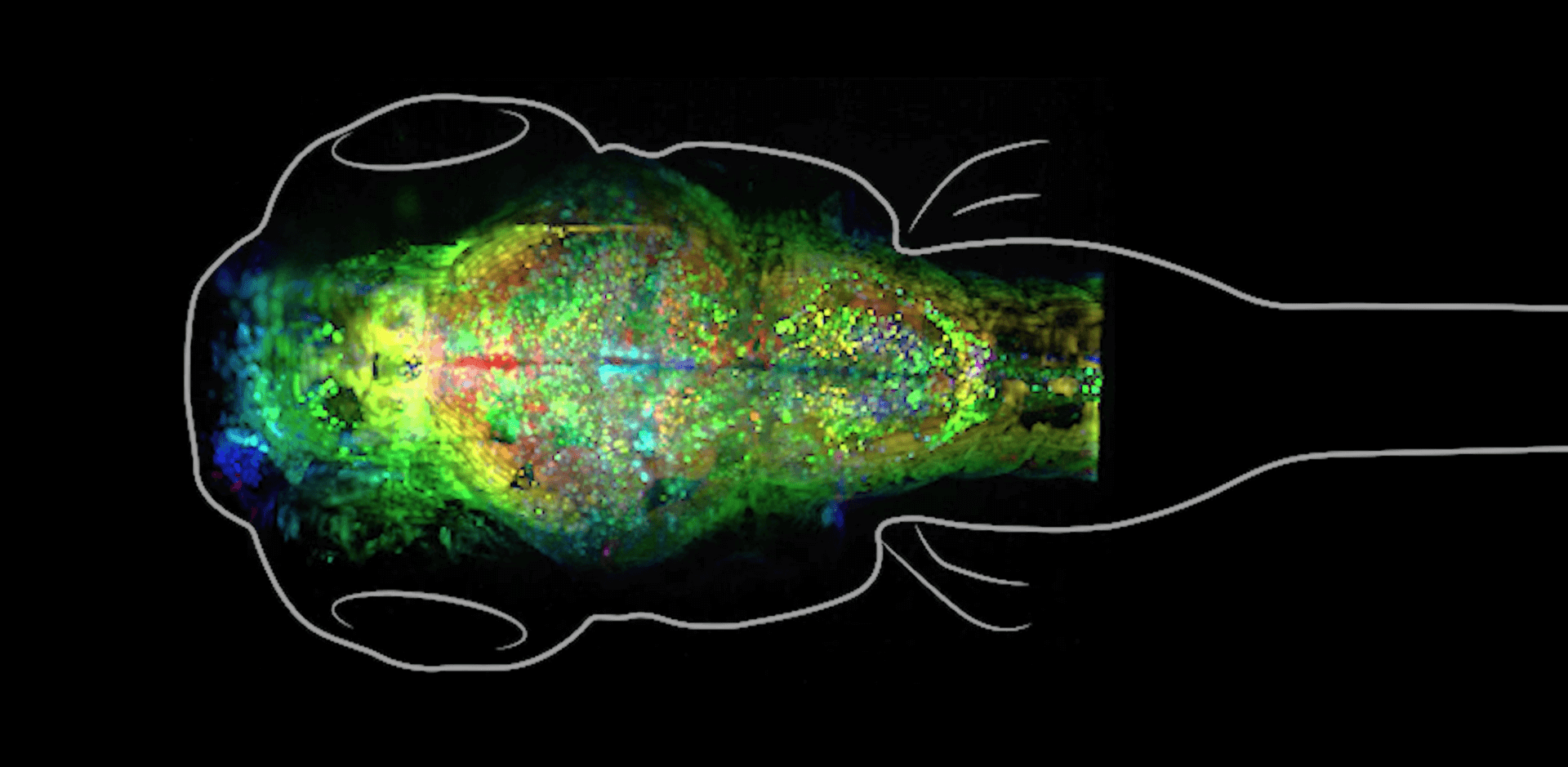

“We use incredibly {light} sensitive cameras,” said Andrey Andreev, a graduate student in Fraser’s lab. “They’re very similar to cameras people use to look into space, or on telescopes, to collect the single photons coming from distant, dying stars.”

The cameras, which can capture 3-D images, are specially built by optics wizard Thai Truong. “We pride ourselves on building microscopes that redefine the impossible,” said Fraser, one of the world’s foremost imaging experts.

Action.

On a soundstage the size of a sugar cube, Fraser’s team is filming “the dialogue between tens of thousands of individual cells.”

Can a zebra fish count? What do the neural circuits look like? Is there a math gene involved? According to Fraser, it may be surprising that animals from cows to crows may have a sense of numbers. For a zebra fish is one, in fact, the loneliest number?

“An MRI machine,” said Fraser, “can see a whole human brain with amazing detail, but what it can’t see is the countless number of individual neurons inside that brain.” And that, at least in terms of counting and memory, is where the action happens.

Wardrobe.

The zebrafish neurons can be made to express fluorescent proteins that change their brightness when each neuron is active, so they are wearing their brain on their sleeve. After all, the zebra fish need to look good on camera.

“If I could spray paint your head fluorescent orange,” said Fraser, “it would be much easier to pick you out of a crowd. We can do the same thing with individual cells.”

The future looks even more specific: Don Arnold, a USC Dornsife neuroscientist, has engineered a special variant of a natural fluorescent protein that will light up and label individual synapses that connect neurons.

Post-production.

Kesselman, a USC Viterbi Dean’s Professor of Industrial and Systems Engineering, has created the software tools to identify, sort and store the footage from Truong’s cameras in a huge database.

Said Truong: “After the ‘movie shoot,’ we do computational analysis to distill all of this footage into meaningful insights. That’s like the editing phase.”

Sequels.

In terms of upcoming video releases, they may be a bit of a snooze.

“The next movie we really want to make,” said Truong, “is where we see – not just how a memory is formed – but how it is then transformed during sleep. There’s a lot of evidence that sleep is critically important for how memories are consolidated. We’re pretty excited about this.”

The New Studio.

“Just like a movie studio is an assembly of a lot of different technologies,” Fraser said, “we need that same thing to study the biology of learning and memory. The people that understand protein machines, data science and imaging must all be in the same room together.”

That “same room” is, in fact, the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, a 190,000 square-foot, high-tech research facility supported by a $50 million gift from retired spinal surgeon Gary K. Michelson and his wife, Alya Michelson. The center, which opened last November, brings together engineers and scientists all under one roof to foster biomedical discovery and innovation.