An Insignificant Life

Becky Singer found her seat on the Eternal Rest Chapel’s Tabernacle of Absence fifth row pew uncomfortable despite the collective effort of hundreds — theorists, engineers, chemists, artisans and robots — to make this moment one of somber remembrance.

Becky Singer found her seat on the Eternal Rest Chapel’s Tabernacle of Absence fifth row pew uncomfortable despite the collective effort of hundreds — theorists, engineers, chemists, artisans and robots — to make this moment one of somber remembrance.

“She’s fidgeting, adjusting her weight distribution from her right to left buttock and back again,” the Tabernacle’s Computational Server said to Pew Seat Sensor (PSS) 5.1, monitoring Becky.

“Readjusting localized lumbar support to begin initialization of more stable seated environment,” PSS 5.1 reported to the server.

Becky felt the seat pressure against her lower back shift while the pew’s Miracle Wood readjusted its sculpting contours. She glanced down at the seat in mild annoyance.

Everything was accounted for: auto-adjusted, ceiling spot track lighting; subtle whiffs of her preferred fragrances shot from pinprick holes in the pew’s carved scrollwork; temperature, hardness and rigidity of the seat itself personally adjusted, everything based on the data monitored by the Ministry, the multinational central depository of randomly gathered bits of information from the remote cameras, sensors and processors, scattered about the world and forwarded along the Internet of Things (IoT).

Becky’s discomfort, however, had nothing to do with her physical seat, or even the room in general. It had to do with her attendance at this service for her father, James Raymond Singer Jr., whom her mother called Jim. It had to do with her suddenly having to sort through the accumulated odds and ends in James/Jim/Father’s apartment.

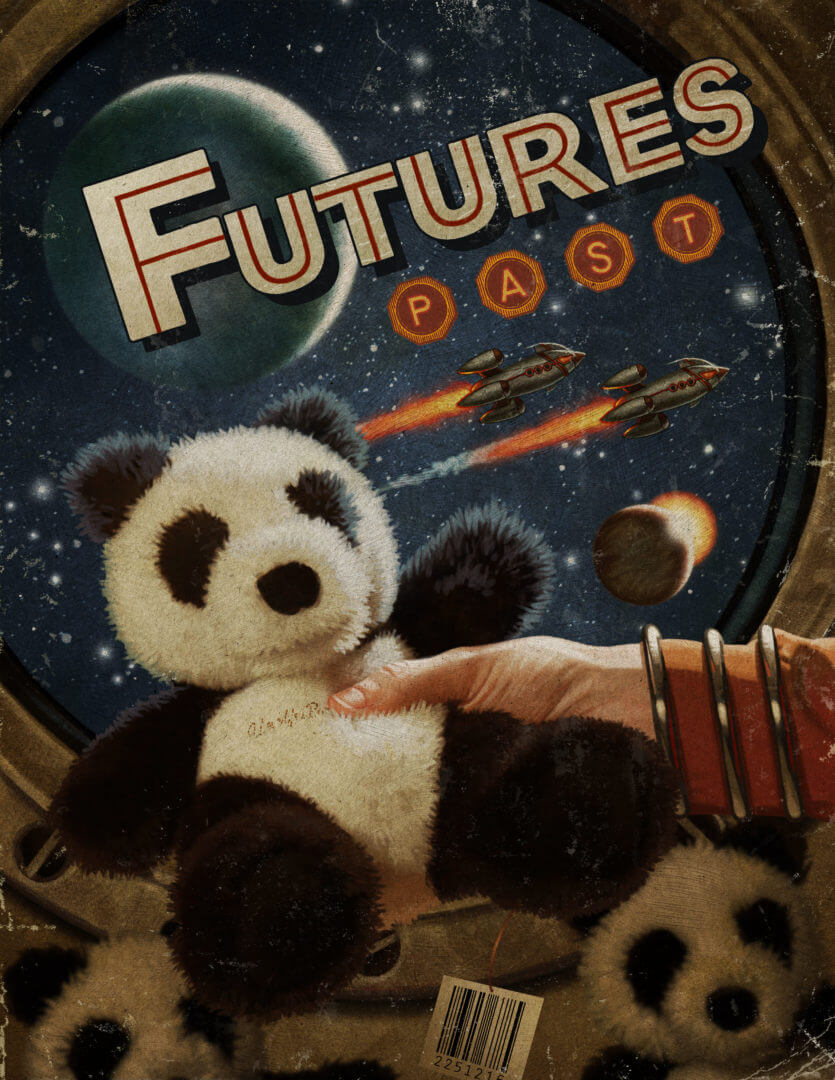

It was mostly junk. Tons of papers (really, who kept papers these days?); computer drives (what is this? 2016?); bits of metals and plastics; that ludicrous stuffed panda bear he’d brought back for her eighth birthday (the party he missed, third in a row); a Mars soapstone carving of an iguana; Titan porous glow rocks that when held to the ear replicated the tornado-like winds of Saturn. Just a pathetic bunch of accumulated junk and a real pain to sort through.

James/Jim/Father was a man Becky barely knew. He had spent his life as an insignificant cog, an accountant/auditor with Trilanta Conglomerate, a stuffy, boring, multinational/multi-planetary concern with wide-ranging acquisition operations.

He had been frequently — well, primarily — off-world, ticking off inventory items and tallying against tallies the raw materials being shipped to Earth or other off-world manufacturing zones where regulations were less stringent than Earth. Her father worked closely with the managers of Trilanta’s lobbyists to ensure operations could be expeditiously adjusted should sudden regulations be shifted to favor one of Trilanta’s competitors.

To Becky, it all seemed dreadfully dull, boring, less than noble. She was thankful she knew less of James/Jim/Father. Even her impressions from the communications with him had been hampered by the lag between question and reply that came naturally due to the distances that waves traveled across space. As a child, she could easily remember watching her father blankly staring into his camera, and after 10 minutes or more, reacting to her question.

As she grew older, she found herself increasingly distracted during this time lag, and found reasons to avoid engaging in these less than engaging calls. Over the years, his “Happy Birthday!”, “You were the main duck in the Fall Festival? Wish I’d been there for that,” “Congratulations on graduating elementary school/middle school/high school/college/second place in the intramural soccer tournament, wow, that’s terrific.” to her felt more obligatory than fatherly.

Becky would have skipped her father’s service entirely, perhaps not even watched the videorecording funeral homes routinely send as part of the condolence package, but she had promised her mother she would attend “should anything ever happen to Jim.” She had read that many now found the whole “funeral service thing” tiresome and maudlin, a waste of valuable, productive time.

Becky glanced impatiently at her eye meter and saw that the service was already one minute late getting underway. She looked about the room. She was alone. Evidently, James Raymond Singer/Jim/Father didn’t have many who would consider it worthwhile making an appearance at his service.

In frustration, Becky began tapping her feet. Pew Rug Floor Sensor (PRFS) 5.1 initiated muffling procedures, though it was hardly necessary, as there seemed to be no one to whom Becky’s toe tapping would be annoying.

“Come on. Come on!” she thought. “Let’s get this over with.”

She didn’t hear her come up, and so jumped suddenly when she was tapped on the shoulder.

“Ms. Singer?” the woman asked.

“When are we going to get this started?”

“Ma’am?”

“The service — when are you going to start the service?

“Oh, ma’am, I’m not with the funeral home.”

“Oh … then you knew my father. Thank you for stopping by.”

“No, ma’am, I never met your father.”

“Then, what …”

“I’m Sharnece El,” the woman said. “I’m with the Ministry of Things, Data Reconciliation Division. My card.”

Becky took the chip-secure business card and immediately saw that, yes, Sharnece El was indeed with the Data Reconciliation Division. Her card’s vidclip showed El at work behind her desk at the local Ministry of Things branch office, Room 3256, located at 1842 Proxima Centauri Place — so it read on the card. You can’t fake a card like that. Well, at least not yet, Becky didn’t think.

“All right,” Becky said, as she attempted to return the card. “What do you want?”

“Please keep the card, Ms. Singer, for your future reference,” El said. “I hate to intrude, but I would like to set up an appointment with you to clear up some of the aspects of your father’s life. For his permanent record, you see.”

“I really, really … really don’t have much information that I could provide,” Becky stammered. Just get away from me, she thought, please just get away from me.

“It would only take a few moments, and at your convenience,” El insisted. “I really must close the record.”

Mercifully, the piped-in, solemn, yet strangely life-affirming string instrumentals began to play, announcing the commencement of the service. The wall vidscreen at the front of the Tabernacle began to project 3-D stills of her father’s life and on various off-world assignments, alternating with nature pictures like pristine forests that no longer existed and wildlife morphed into those former landscapes. Many of the stills and videos had been culled from the Ministry’s data archives.

The picture widened to allow for the inset of the prerecorded holographic nondenominational clergy, whose appearance would adapt for each mourner’s viewing based on the mourner’s microbiome-registered preferences — gender, race, vocal qualities — who would eventually lead the service, but who now watched as the fantasy unrolled.

Becky could hear the distant whirr of the gears controlling the 3-D cameras as they turned to cover her for inclusion in the video playback remembrance. Yes, there had indeed been someone in attendance at James Raymond/Jim/Father’s service. She cynically wondered if the Ministry ever morphed in other mourners to make the services seem more popular for the permanent record. She did not notice the PSS 5.1 adjusting her seat after her bout of cynicism.

“Please, Ms. Singer. I promise not to take too much of your time.”

“Yes, yes, yes, all right, all right, all right.”

“Thank you, Ms. Singer. I’ll be in touch.”

As El backed respectfully away, Becky returned her eye to the vidscreen and wondered just how long this interminable introduction would take.

That night, Becky lifted the first box of disposables and crossed James/Jim/Father’s apartment to the front door. The floor sensors noted her additional weight, her non-deviational course to the door, and relayed that data to the Apartment Building’s Computational Server (ABCS) and …

“Open front door,” ABCS ordered.

The sensors in the door clicked, and the door swung inward.

Becky nearly dropped the box in surprise. She hadn’t expected El.

Taking a deep breath, Becky said, “I thought I was rid of you.”

“Well, you mentioned you were disposing of your father’s effects, and I thought if you didn’t mind I could just have a look about.”

Becky frowned in disgust, dropping the box, which landed with a thud — shorting one of the floor sensors, initiating a frantic redirection of coverage to compensate and sending an emergency repair request to the building’s RoboSuper.

Becky threw her hands apart with a magician’s flourish, and said, “Look about.”

After a moment, El crossed, stooped, then began to carefully rummage through the box. After a bit, she pulled out the Titan glow rock and pressed it to her ear, smiling slightly.

“I used to love listening to these as a little girl,” El said.

“I’m sure you did,” Becky said. “Keep it.”

El frowned slightly and replaced it in the box, then noticed something. She reached in and pulled out a tiny chip of broken plastic.

“Oh, my! It can’t be!”

“But it is.”

“It’s impossible,” she quickly reached into her purse and pulled out an iProj scanner/projector. She aimed it at the chip of plastic and swiped at the lever. Lights flashed as the scanner searched the Internet of Things for a recognition. Suddenly, a 3-D projection of the chip appeared.

“It is,” El said with a gasp.

“It is, what?”

“This was a chip from a KX stabilizer in the right wing of the Inesco Space Transport.”

El stared at her, certain Becky would understand the importance of that.

“So?”

“You really don’t know?”

“No! I really don’t know.”

“Your father was checking against a cargo manifest in the hold of the transport Reliant when he noticed that chip of plastic. Only he noticed it.”

“And?”

“He reported it. You see, your father noticed that chip, it was odd, and an investigation revealed there was a flaw in the tempering process for the final molding of the stabilizer. Computer simulations revealed an 87 percent chance of a catastrophic failure in the Inesco Space Transports as they docked, should the stabilizer fail. A failure would cause the transport to, um, spin out of control at spaceport causing considerable damage. With 12,480 transport passengers per day passing through spaceports, a crash would be catastrophic. And that’s just the Mars space transfer port. If all ports experienced a simultaneous transport event …”

“But because your father was on the job, paying attention, was curious about why that tiny chip of plastic was stuck in the seam between the floor and the cargo hold, he saved who knows how many lives. He received a commendation. May I have this?”

For a long moment, Becky stared, then, “Sure.”

El removed a small specimen zip-lock bag from her purse and with reverence slipped the chip inside. She continued to look through the box, but nothing further seemed to interest her. Then she glanced back to a box piled high behind Becky. She crossed to the box.

“May I?”

Becky nodded her head.

El began to rummage about. She stopped, lifting up the Martian soapstone carving of an iguana. She shook her head.

“Ridiculous, isn’t it?” Becky said.

“Yes, no iguanas on Mars,” El said. “You know, the miners like to carve these, sort of like the days of the whalers in Nantucket who would make elaborate scrimshaw carvings on sperm whale teeth to pass the time.”

“It’s meaningless then,” Becky said.

“Well, I can’t be sure,” El said. She ran the pocket scan over the iguana, but no lights came up. “I can’t be sure.”

“On Mars, there was a miner named Otis Jolivette. He used to make carvings of reptiles. Otis was depressed, tired of the isolation, the separation from Earth. Your father encountered him as he was about to step out from an air lock into the Martian atmosphere without a suit.”

“Good Lord!”

“It’s what the old timers call Red Rapture, the accumulated effects of too long a contract on the Red Planet. Your father managed to talk him out of it and was able to get him to talk to the company psychiatrists. He was sent back to Earth for R&R.”

“That was good.”

“But what was incredible — and I don’t think your father knew this — was that because Otis was back on Earth and being treated at the Geneva Clinic, he was in the right place at the right time to prevent Dr. Agnieska Lorente from being run down by a Geneva Street Ship. She was so focused on finding the solution for spatial blight contamination around Terran launch sites and on spaceports that she ignored warnings and stepped right into the flight pattern of traffic.”

Becky stood, taking it all in.

“No, I don’t think your father knew about the Jolivette-Lorente connection.”

“How do you?”

“Backtracking along the Internet of Things. After your father died, as I was assembling his file, I noticed the connections. If your father hadn’t succeeding in getting Jolivette R&R, Jolivette would not have been in Geneva to save Lorente from being run down and we would not have had success conquering space blight. That greatly increased CO2 to O filtration efficiency at transport docks.”

El glanced across the room and suddenly noticed a ragged, stuffed panda bear atop the third box of disposables.

“Gee.”

She stood and crossed to the box, picking up the panda.

“That was my father’s cheap apology for missing my eighth birthday.”

El ran the bear across the iProj pocket scanner/projector.

Suddenly a 3-D video playback of her father, much younger, in a spaceport gift shop carrying a much newer looking version of the panda appeared above the iProj.

“This is keyed off the bear’s SKU at the point of sale, preventing shoplifting, credit fraud.”

Her father, in a hurry to pay, suddenly notices a woman’s distracted, troubled, demeanor. He pauses, speaks kindly to her.

She looks up at him, and begins to cry slightly, explaining what’s troubling her.

“What’s going on?” Becky asks.

“Your father has just met Margo Kittridge. She just learned that her son was one of those missing in a mine collapse on Titan, but has been unable to get any other information on the status of the rescue efforts. She’s frantic, but feels she needs to keep working to take her mind off the helplessness she’s feeling. Your father will make some inquiries, call in a few favors, in order to get a detailed report on the rescue efforts.”

“Was he…?”

“No, he was found alive, about an hour later, pulled out but with a broken back. Your father had stayed with her in the gift shop, missing his connecting flight, until he got word from Titan that her son had been recovered. He did get into a bit of trouble with his bosses for missing his connecting flight, and a meeting on Earth had to be delayed, not to mention an eighth birthday party. However, your father had a solid reputation, and was not a man Trilanta could easily dismiss.”

“Why would he do that?”

“Because somebody once took time to listen to him. There’s an old proverb about dropping a pebble in a pond. You never know where the ripples go. Did you know there’s a recorder in this? If he did it correctly, you would have been able to feel his hug through the bear and hear a personal message? Of course, you need to know how to trigger it.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Would you like to know how?”

As El exited through the sensor-controlled automatic doors of James Raymond Singer’s apartment building, she smiled to herself. She clicked on her wrist phone.

“El here,” she said into the phone. “Grief counseling for Becky Singer completed. See you in the A.M.”

That night, while lying in her bed, in her own apartment, Becky watched the playback of James/Jim/Father with Margo Kittridge on her iProj console. After the fourth viewing, she picked up the tattered and worn stuffed bear. Hesitantly, and feeling a bit foolish, she kissed the bear’s left cheek, then right, then pressed it to her face. There was a pause as the sensors in the bear’s head sought to retrieve the long ago recorded message, stored in the Ministry’s data collection by the Internet of Things.

And just when she thought it was pointless, that she should set the panda down, it’s arms suddenly stroked her hair and she heard her father’s voice, in slight jumps, indicating he’d paused and restarted the recording several times, coming from the panda’s mouth.

“Sweetie Petey, I’m sorry I missed your birthday. I miss too much of your life. Please know that I do love you and your mother. It hurts. I hope someday you’ll understand. Good night, sleep tight, and lots of butterfly kisses for sweet dreams.”

She blinked back a tear and stared at the bear. She could just make out the embroidery, which had faded. There was some stitching missing, but the needle holes completed the lettering. She could just make out, “I love you beary, beary much.”

“I love you too, Daddy.”

END

Ted Elrick is a graduate of the American Film Institute (AFI) and active member of both the Writers Guild of America and Mystery Writers of America. In addition to short stories and nonfiction magazine articles, he wrote for Nickelodeon’s live-action Twilight Zone-type show for kids called “Are You Afraid of the Dark?” as well as the feature film “Home Sweet Hell” starring Katherine Heigl and Patrick Wilson.