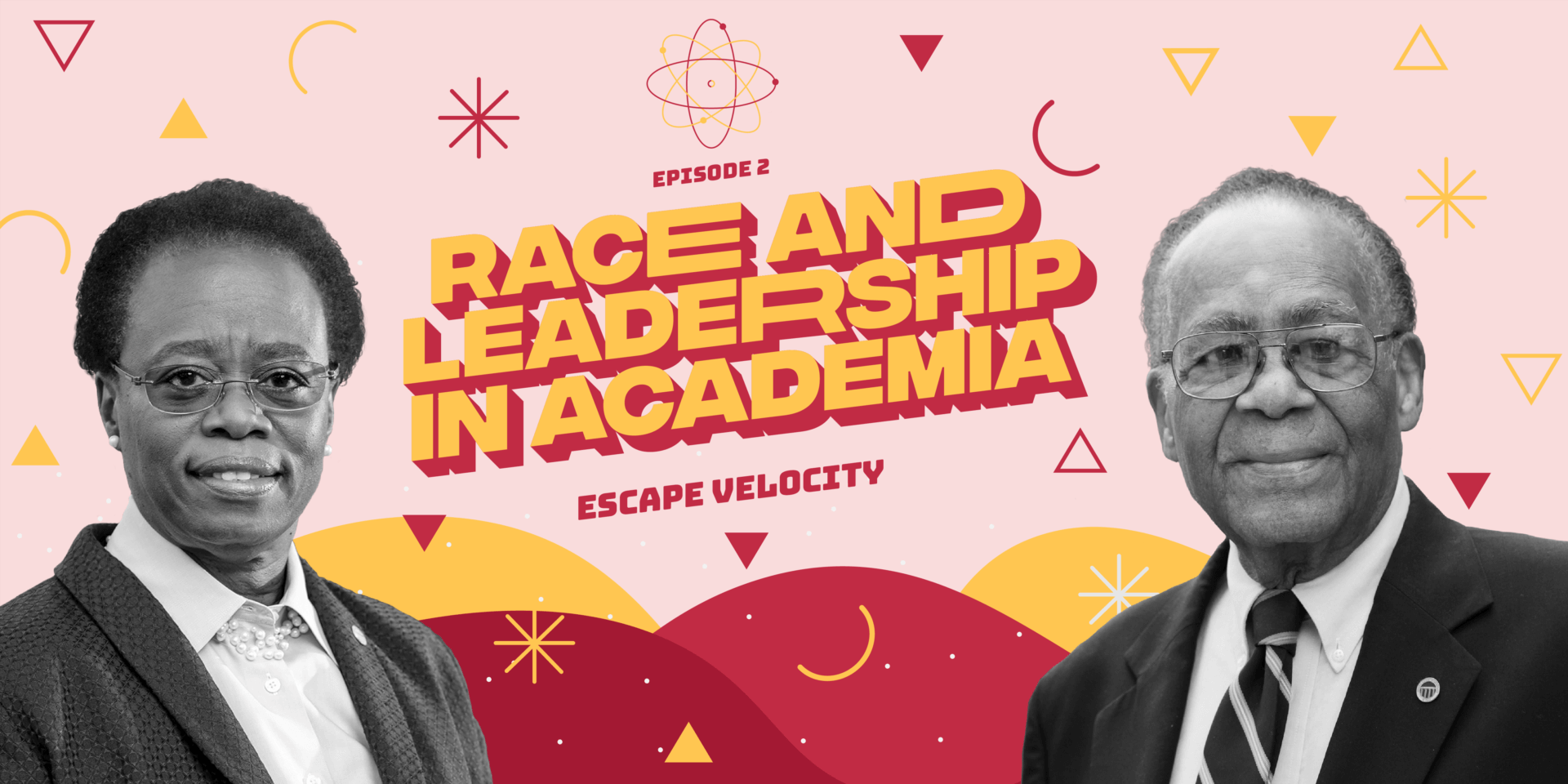

Escape Velocity Episode 2: Race and Leadership in Academia

The USC Viterbi School of Engineering’s podcast series “Escape Velocity” originally launched in 2016 as an audio drama series capturing the intersection of engineering and everyday life — stories of love in a time of algorithms, unlocking the human body and even an old school radio drama about AI buildings as friends.

Now, it has been reimagined in partnership with Brandi Jones, USC Viterbi vice dean of diversity and strategic initiatives, to capture the intersection of race, academia and STEM.

Race and Leadership in Academia

Wanda: Good morning, and welcome to the 136th annual commencement of the University of Southern California.

Cheering

Wanda: We celebrate graduates from all 50 states and nearly 120 nations, representing hundreds of fields and specialties. Knowledge and discovery are accelerating at a rapid rate. Industries that have dominated for decades are being disrupted on a daily basis. Traditions that have lasted for ages are being swept away by the swift currents of change. It’s been said that change is the only constant in life. For individuals and institutions, change can also be a great force for good.

John: The most important thing that I did, was to make the statement that Black studies was for white people, and math physics, and chemistry was for Black students. Now that may sound a little ridiculous on the surface, and highly questionable, and unduly simplistic, but I feel it more strongly today than I did at that time, given the level of underrepresentation of minority students in science and engineering, and the fact that the level of racist comments and behavior is at a level in our society, and even on the most respected college campuses in this country. That, we all have to find deplorable.

Dan: From the USC Viterbi School of Engineering in Los Angeles …

Brandi: This is “Escape Velocity.” I’m Dr. Brandi Jones.

Dan: And I’m Daniel Druhora.

Brandi: Today we are going to listen to two leaders, in academia and in industry.

Dan: Dr. John Slaughter and Dr. Wanda Austin, both members of the prestigious National Academy of Engineering. Both have served as Presidents of major universities. Google them, and you’ll find a long list of historic first for each of them. For every institution they’ve led, they were the first African Americans to hold those positions. In Austin’s case, also the first woman to do so.

Brandi: Dr. Wanda Austin, who also happens to be a USC Engineering alumna, is the former president and CEO of the Aerospace Corporation, a leading architect for the nation’s security space programs. In 2015, President Barack Obama appointed her to serve on the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. A year later, she authored a book titled, Making Space: Strategic Leadership for A Complex World.She then became President of the University of Southern California, guiding the institution through a crucial transition period.

Dan: In 1980 President Ronald Reagan appointed Dr. John Slaughter as the director of the National Science Foundation. He returned to higher education in 1982 as Chancellor of the University of Maryland, where he made advancements in the recruitment and retention of African American students and faculty. In 1988, Slaughter was appointed President of Occidental College, and transformed the institution through his 11-year tenure into the most diverse liberal arts college in America. He joined USC in 2010 and holds professorships in both the Viterbi School of Engineering and the Rossier School of Education.

Brandi: Both Austin and Slaughter have advised presidents, boards of major corporations, and CEOs.

Dan: The two long admired one another. Austin said one of the highlights of her distinguished career was presenting Slaughter with the USC Presidential Medallion in 2019, the University’s top honor.

Brandi: Today, Dan and I are going to stay out of the way and let these two extraordinary leaders do the talking.

John: We haven’t made a heck of a lot of progress. We can point to some improvements. But we certainly don’t have any laurels to rest on. I still feel very strongly that the most important thing that we can do in our schools of engineering, in the STEM disciplines increase the numbers of persons who have historically been underrepresented in the STEM fields. If we’re going to be able to solve the wicked problems that this world is facing.

Wanda: We often hear the characterization of a white woman walking down the street and three or four black guys are coming at her, and she grips a purse and maybe even wants to dart to the other side of the street. And, you know, when we think about why it’s so important for our universities to be inclusive and to make sure that we’re reaching into all communities and particularly into the African American community is because she, if she could see them coming and can see, Tommy Trojan, Oregon duck, Stanford tree, even a Bruin, it would put her mind at ease, right? You know, Okay, I understand where you’re coming from. As long as I’m not wearing one of the opposing sweatshirts, you know, we’re going to have a good interaction. And so I just get back to our sort of fundamental point here about why it’s important to make sure that our student and faculty are representative and inclusive, it’s because we have to make sure that all of those communities feel like they have access to a quality education because that changes the world.

John: That’s something that is very important.

Wanda: In my short time here as President, I can’t tell you how many times students would come up to me and say, when we saw you announced, it really lifted our spirits because we knew that someone would understand the challenges that we face, and you don’t realize the impact. I can tell you I did not realize the potential that impact even though as I reflected on my view of Dr. Slaughter, it clearly had that impact for me. And so it continues to be very important that students and faculty feel like this is an environment where we are striving to make sure that they feel comfortable and we’re striving to make sure that they’re able to achieve their potential that they don’t have to overcome an inordinate amount of challenge in order to be as successful as the person sitting next to them. And frequently, I think that certainly African American engineering students feel like their burden is larger, or their challenges are larger. They have to, you know, be twice as good three times as good in order to be considered and that can take the wind out of someone. It really can.

John: One of the things we have to confront is the fact that there are people who believe an emphasis on diversity and inclusion means a de-emphasis on quality. I’ve certainly encountered in my experience early on at Occidental. I said that true diversity occurs at the intersection of excellence and equity. People were puzzled about what that meant. It required a lot of convincing. I said the diversity doesn’t make sense if there’s no excellence in the environment. The penitentiary is diverse, but nobody wants to be there because no excellence. And by bringing in some really bright minority students and minority faculty we were able to overcome the resistance.

Wanda: I would underscore that and say in addition, what we’re trying to do is, you know, raise our IQ above the board. The other way it’s sometimes thought about, I believe, is that somehow if we have more diverse candidates that someone’s losing, something’s being taken away. And, again, I think that you’ve got to remember what our objective function here is. It’s always Excellence. it’s an argument that you hear. But I also point out that everybody gets to vote with their feet. So over time, you could say we there’s no value in being diverse in our faculty, but I would tell you over time, you would find that your student population also would not be diverse because diverse students would say, I don’t feel that I can learn there because there’s no diversity of thought, in the faculty, there’s no one there that really has can relate to any of the experiences that I’ve had or is making sure that as they think about the world, that they’re reflecting diverse opinions, your customer base, the people that you’re interfacing with in the community, again, you can talk about it, but when you don’t have results to show, eventually they say, you know, all talk, no action.

Announcer: Let’s keep things going with the presentation of our next award. Here to present the 2015 Chairman’s Award is the chairman and founder of GMIS himself, Mr. Ray, and Chairman of Washington State University and GMIS board member Dr. Keith.

As an educator and an illustration, Dr. John Brooks Slaughter is a living legend. An electrical engineer whose research focused on the fundamentals of algorithms computing, he spent the better part of his six-decade career leading the nation’s finest academic and scientific institutions. However, it’s been his advocacy for expanding opportunities in STEM for underrepresented students that has won him universal praise.

John: You know, I learned so much about myself during that period because I had never experienced hate. I thought people liked me. And then I received letters that said things like, “When you’re driving home, look in the rearview mirror because we’re going to be behind you.” Or death threats.

Wanda: Intimidation

John: I drove into my parking spot that morning and there was a sign there, “Go away nigger.” I received letters that would curl your toes. I kept them.

Wanda: I didn’t keep them. It was just that toxic. I read every one, but I didn’t keep them.

John: I kept mine.

Wanda: No, I sent them to the lawyers. They can keep them.

When I grew up, it’s in the 60s. It’s in the inner city of New York. My father is a barber. My mother is working as a nurse at night. So, when you think about what’s in the realm of the possible, my church members, my family members, you know, looking at this little black girl, not wanting her to be hurt or disappointed, would say, Oh, you know, maybe you could be a teacher or maybe, you know, you could, you know, be able to get a job but you know, certainly not talking about trying to go to college or really have a professional career and so I don’t fault them for that, because they were coming from their experience about what was possible. I remember, in the summers, we would go down south to visit relatives and my parents having to explain to me, okay, you have to use the colored bathroom, you have to use the colored water fountain.

But the thing that my parents knew, and I give them a lot of credit for fighting for it was that education is no doubt the equalizer. No one can take that from you. It cannot be discounted, it is real. So, your job is to get a good education, you can screw up everything else. But you don’t bring home bad grades because the education is the key to your success. It wasn’t until I went to seventh grade, that I had Mr. Cohen as a teacher, as a math teacher. And I remember working on a project, I finished it, other students were not able to do it. And he said to me in front of the foot in front of the whole class. You’re good at this. And don’t ever let anyone tell you that you’re not. What an empowering statement and to say it publicly not just whisper it Okay, little girl. No, I want everyone to know that you are very, very good at this. And to make sure I was good at it, he gave me lots of extra assignments, lots of extra puzzles got me a subscription to a math magazine. I mean, so he followed it up with the support and encouragement so that I would have the confidence that I was good at it. And we’re still in communication to this day as a result.

John: I was struck by your comment. When you were young, you had no idea what an engineer did. I grew up in Topeka, Kansas in Topeka. If you were an engineer, you ran a locomotive. So, I had no idea what it was about. I just like to tinker with things. I tell people I used to tear my bicycle down once a week and put it back together again, to be doing something. And that’s what led me to be an engineer. In eighth grade, I said I want to be an engineer. People laughed at me not because I wanted to be an engineer, but they never seen a black person who was an engineer. It’s amazing how we end up in these fields.

Wanda: Absolutely, absolutely. My career started in mathematics. And the simple reason for that one is I had encouragement from home because my mother loved to take me to the grocery store with her because I could tell her to within a couple of pennies what her bill was going to be. This of course was before ATM cards and credit cards. You had to have cash no kidding when you got through the, the counter. So, I had value as a mathematician in that respect. But the other thing about math is, it was independent of race and judgment. If you did your work, you could show someone how you got to the answer that you arrived at. And if they told you, you were wrong, they had to also tell you where you made your mistake. A lot of other subjects were very subjective. And you were subject to what someone saw as being a possibility for you. And I had experiences where people would say, Oh, no, you you’ll never understand English literature. Oh, no, this is not the right field for you. But mathematics. If I did my work, it wasn’t up for debate. And so that’s how I ended up in mathematics. And when I discovered the mathematics was a door to solving problems and you know, really being able to impact society. I thought I’d hit the lottery.

One of the things that this time has brought us of being in a pandemic is that we have the attention of everyone because everyone has time to pay attention. A year ago, everybody was running, and no could hardly spend a little time on social media to find out what were the big events of the day. But today, people are having an opportunity to really reflect on things that were taken for granted. To the same extent, I think the university has to hold the mirror up and look at itself and saying, Are we really, if we look at ourselves critically, doing the best that we can to serve our customer base, being our population of the world to make sure that we’re giving everyone access and the opportunity for the best education that they can have? And if there are barriers, whether intended or not, that we are placing that prevents groups of people from getting that access. Shame on us, because our mission says that we won’t do that. Our mission says that we will work to provide access for everyone.

John: It’s wonderful that they can have programs that go into the elementary and secondary schools and so forth. I don’t think that’s enough. I think what we have to do is to work much more closely with the with the teachers in elementary and secondary schools and identify the bright young people very early on in their education and guide them. mentor them throughout the process, not wait until they’ve graduated high school and when I was in NACME we found out that only 4% of minority children are prepared to enter engineering school. So, if we can identify them at an early age, identify them at the fourth grade when they’re doing well. And start mentoring them, start encouraging them, then guide them through the rest of the education, guarantee them if they do well, an entry into a college or university, continue to mentor them, help them understand what it means to get a graduate degree. And I think that at that point, we could possibly have a cohort of young people who could be prepared to ultimately enter the professor field that I think until we become more proactive, it’s not going to happen.

Wanda: Proactive is what’s required. And I think you’re right that in fourth grade is the perfect age. And there’s a lot that you can introduce to a fourth grader that you don’t call it engineering, but it is engineering, it’s problem solving. It’s helping them to understand the so what will I be able to do? Because I’m pursuing an engineering curriculum. And for many young people, it’s amazing what they will figure out, if you give them the opportunity. Don’t try to give them the solution, give them the opportunity to think and to figure it out.

Speaker: On behalf of my fellow trustees, congratulations to our amazing graduates. I have a surprise this morning, and it’s a good surprise. It’s a surprise for a person who has led this university through probably the most challenging period in our 140-year history. Upon the recommendation of the appropriate university committee, I have the honor of presenting you, Dr. Wanda Austin as a candidate for the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters.

Loud cheering

Speaker: It’s the best surprise all year. And we know you don’t need another degree.

Brandi: We as an engineering school would argue, we’re doing a lot in the K-12 space. But clearly, either we’re not doing enough, or we’re not doing the right things. So, what might we do to make a shift?

John: I think there’s going to have to be a revolution, very frankly. In the sense that engineering is not a field that embellishes social justice. Engineers are not educated in the area of social justice. And most white engineers have not really given a lot of consideration to some of these issues. Some years ago, when I was at the University of Maryland, I co-taught the class of African American Studies, and the first day I walked into the to the class I wrote up on the blackboard, something that I refer to as Slaughter’s theorem. And it was white students, black students, Black Studies is for white students, math, physics and chemistry are for black students. That was a lot of hyperbole and so forth. But if you stop and think about it, I think it is a very serious, important message. We need to at a very early age not only educate our black students, as we’ve been talking about, but we need to educate white students as well, they need to understand the history, the history of black America. And I think if they had a better understanding of the history of black America at a very early age, at the time when they are ready for entering say, like engineering school and becoming engineers and ultimately engineering faculty, they’ll have a better appreciation for what it is that these young people have gone through and why it is essential for them to be prepared to mentor as well. I’m encouraged by what is going on right now. In the country and in this area. Hopefully, that’s going to lead to a better understanding for everyone. There is no excuse any longer for people to say I didn’t know.

Wanda: I would second that. And I would say that it’s really critical for all faculty to recognize that their job is to find the genius in the room and nurture it. And make sure that it gets the water and sunlight that it needs to be successful.

John: As you know, I grew up in Topeka, one of the four Black elementary schools in Topeka, prior to the Brown v. Board of Education case. Even though we lived in a mixed neighborhood, most of my friends when I was little were, many of my friends were white children who lived in the same neighborhood and we played sports and everything together and visited each other’s homes. And we would walk to school together, except that we would leave them three blocks from our house and say goodbye to them and my sisters and I would walk another eight or nine blocks to our school. You had a feeling that something was wrong, but you couldn’t quite put your finger on it when you were little. And even though we were good friends, we would meet up after school and fight, because of this feeling that something was wrong. And in eighth grade, as I mentioned I decided I wanted to be an engineer. I wrote a paper in English class in eighth grade and said that when I graduated from high school, I wanted to go to either Kansas State or the University of Kansas and get an engineering degree. So, I told anyone within earshot that I wanted to be an engineer. People got tired of hearing me say that I think. Anyhow, I got to high school and high school was integrated, although socially we had very little contact with the white students, there were separate parties, we could not participate in some of the athletic events, we were excluded from a lot of things. When I first went to the high school, I told the counselors that I wanted to prepare to study engineering, and the counselors said, “Oh well you need to go to trade school.” So, I ended up learning how to repair radios. I didn’t take the math, science, that I should have had if I wanted to be an engineer. When I graduated, I had very good grades, but I didn’t have what was necessary to go to Kansas State or the University of Kansas. I ended up going to a small liberal arts college in my hometown and took the courses that I should have had in high school. I considered that the worst thing that could happen to me at the time, but as I have told many people, in the long run, it may be the very best thing that could have happened. Because I got the chance to take courses in economics and history of English literature, and world history, and speech and a number of things that engineering students at that time didn’t normally take. And so, when I completed two years there and had the background, I did enroll at Kansas State, and my peer engineering students were much better in the science and math than I was, frankly, but I knew so much more than they did. I’d tell people that I wouldn’t be the president of Occidental college if I hadn’t gone on to take those liberal arts classes.

Brandi: So, we’re at a point in time where nearly every university president and nearly every engineering dean is asking, what can we do? What should we be doing? What should the actions be?

John: Yes. Particularly as it as it refers to, how do you increase the faculty? That’s an issue that I feel very strongly about. When I was at Occidental, I was fortunate to have a Dean of the Faculty and faculty leadership that was as committed to diversifying the faculty as I was. And we found that there was a program that existed, not a lot of people knew about whereby you could work with some of the best universities in the country. Harvard, Yale, Michigan, Wisconsin, even USC, and identify PhD students who are a year or so away from completing their degree, invite them to come to Occidental to complete their dissertations. Perhaps teach a class, spend a year doing that, at Occidental. Give us an opportunity to observe them, see if there’s someone that we would like to have on our faculty, give them an opportunity to observe us. And we had considerable success in attracting them and retaining them. the one thing I’m most proud of about my experience during the time that I was there, 11 years, and Occidental is a lot smaller than USC. So, our faculty numbers are much smaller, but we hired 65 tenure track faculty members during that period of time. Half of them were women. Half of them were people of color. And I don’t think there was another college or university in the country that could claim that kind of success. So, when people do call me and ask me any advice that I can offer? My answer is, you cannot simply advertise for minority faculty position. I had a faculty member in science at Loyola Marymount, who said that we cannot get minority faculty we advertised in Science. we advertised in the Chronicle of Higher Education. You know, I said stop, stop advertising in Science stop advertising in Chronicle of Higher Education, advertise in Black Engineers, in Black issues in higher education. Go where they are. Go to North Carolina. Go to Tennessee State. Go to Florida A&M. If you’re serious, you’ve got to be active. And so that’s my advice to them.

Wanda: You’ve got to find ways of accelerating the process. And one that comes to mind that I’ve offered to people who’ve asked – use the adjunct faculty role as a way to connect with people in an industry and find the diverse candidates and bring them into the classroom because that gets them in right away. It gets them to the relationship with the existing faculty. And this is a win-win for everyone, it at no risk. For people that are looking for a quick fix or you know, a stamp or sticker that says, okay, we did that check. You know, we advertised, you know, our obligation is done. You can’t You can’t come at it that way. You have to be results oriented. And if you’re not getting the results, you need to change your actions. I think you know, providing grants and partnering with HBCUs to make sure That you are floating everybody’s boats, if you wanted to do joint research projects, and you have an institution that doesn’t have the resources that you have, then figure out a way to make sure that those students are able to work at the state of the art. One of the things that we’ve learned, and I think we knew it, but it now has just been put right in front of our faces, as we have gone through this pandemic, is that black and brown children are tremendously disadvantaged from the start. So, when you say that we’re going to do Virtual Education, we’re going to, you know, teach and have kids stay at home and same thing I’m sure with our undergraduate students, some of them come from situations where that is a non-starter. It’s a meaningless, meaningless statement to say we’ll just get on the internet and work from home? Well, there’s no computer access, there’s no Wi Fi, there’s no one around you to help get that set up. And so you have to recognize that sometimes it means really getting down to basics to make sure that you aren’t disadvantaging a group of people, because you just didn’t realize that the things that you take for granted, they don’t have access to, and therefore you need to address that basic need that that’s not being met.

Dan: As the Dean of one of the top engineering schools in the nation, Yannis Torsos, an immigrant scholar from the Greek island of Rhodes, finds himself at the forefront of implementing the strategies that Dr. Austin and Dr. Slaughter are talking about. Here he is in 2017, after receiving the highest honor being bestowed upon a school by the American Society of Engineering Education, for his efforts in spearheading the Dean’s Diversity Initiative. To date, more than 230 Engineering schools have signed a pledge to diversity.

Speaker: We’re joined now by Yannis Yortsos. He is the Dean of the Viterbi School of Engineering at the University of Southern California. Yannis, Welcome.

Yannis: It is my pleasure to be here.

Speaker: So, you just won the President’s Award, a huge honor. How does it feel to be recognized by your peers?

Yannis: So, at USC, we’ve been pushing for quite a while now, changing the conversation about Engineering, that engineering is much bigger than simply algorithms and devices. Having a much broader mindset, and of course increasing the pipeline, the pipeline in underrepresented factions of the population in engineering.

Speaker: So, speaking of representation, you’ve been busy working on the Dean’s Diversity Initiative, right so tell us about this initiative.

Yannis: I happen to be the chair of the diversity committee of the Engineering Deans, about 2 years ago in 2015, I happened to chair a session on diversity in engineering, that session is actually where we decided that it’s about time to stop whining and take an action. So, at that time, we created a commitment, which is about four points. We asked engineering deans across the country to pledge to that. And these four points included: creating a diversity plan, doing a K-12 outreach, partnering with institutions that are not simply research universities, and fourth, diversify your faculty. So, we started this effort back in June 2015, with zero participants, by August 2015 we had about 102.

Yannis: Where we do not do well is on the PhD pipeline, as well as on the faculty pipeline with respect, particularly to Hispanic or African American talent. The numbers are not some where we want to be, that’s for sure.

Daniel: Where do you want to be?

Yannis: I don’t want to go with numbers per se, but you know, you want to make sure that you have people that can provide alternatives in a way that they don’t feel marginalized and they don’t feel very, you know, sparse. So, you get one person every, you know, 50 people I mean, that’s right now we have in the school, if I count the number of black faculty we have. We have Timothy, we have Stacey Finley, you have John Slaughter. He doesn’t teach all of our undergraduate courses. We have Anthony Maddox who teaches our academy courses. Wade Zeno. He’s joining us next year. Maybe you have five, or five or six. We have Brandi. They’re not a lot. We have 200 tenure track faculty. So, this is a percentage of like two and a half percent. That’s not representative of the world or the community at large. A lot of it has to do with, with perhaps how intentional we are in terms of effort to try and bring in all this talent here. We can do more there and we should do more there, I think there’s no question on that. See, there are two ways by which you recruit, right. One way by which you recruit new faculty is you say, we’re going to put an ad out there and see who applies. And, you know, we’ll tell everybody who applies how good we are and in this and that. The other option is to say how do you approach people that are interested in going to a faculty position and you have to go and recruit those people, the same way that you would do, you see how you recruit talent? How are deans recruited? or Presidents? In engineering, one, we try to recruit people for faculty positions. First of all, we don’t use search firms that we don’t even use sometimes the mentality of the search firms. This is a push pull thing, right? Instead of, you know, simply get the pull, you have to actually apply the push and bring the people over here. And I don’t think we’re doing a lot of this to the extent that we should. And I think this is something that we have to address in a way that is systematic, and you know, so it’s a matter of educating our faculty how to how to get going there.

When you make cultural changes, I understand that it takes about 15% of change agents, people that can make a difference, and therefore, you know, it’s like a catalyst or perhaps, if I use a different terminology, I call this the percolation threshold where you reach a threshold, after which you have a change of phase, you get into a different phase, just like you go from gas to liquid, or liquid to gas, or gas or solid after a particular point, the boiling point or the condensation point or whatever. That’s exactly what you need. You need to have reached sort of a fraction that takes you to the next level.

This is a very seminal time, a very seminal moment. There’s absolutely no question about that. This is where what you value becomes important and actually becomes clear in your minds.

Wanda: I would ask everyone to bring their best self to the table, each and every time. It’s not about making sure the other side doesn’t win. It’s about being the best that we can be as a community.

John: And I would say that this is a really important time for us to recognize that we have an opportunity to finally make America live up to its promise. And our young people are the ones that can make that happen. I feel much more optimistic about the future today than I ever have because I believe that we have a group of young people that can bring this about. So, I would encourage them to make America be the America that we all love and dream about.