A Helping Hand

The shy student from India learned about what he calls the “dignity of labor” while working and studying his way through graduate school at USC Viterbi.

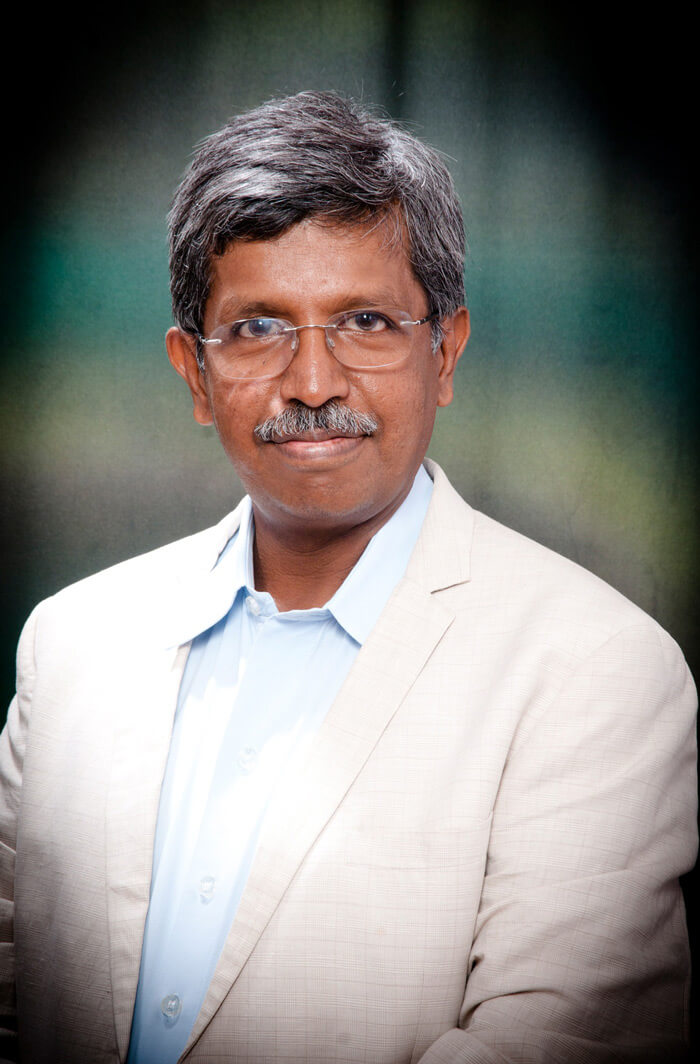

To support himself while earning a master’s degree in electrical engineering in 1985, Narendra Narayanan toiled away in the cafeteria, in the library and in the computer center. He also graded undergraduate papers and worked odd jobs.

The variety of work opened Narayanan up to a world of people from diverse backgrounds. Never once, he said, did he feel like he was doing menial work. And those three years helped shape how the now-highly successful entrepreneur conducts business.

“USC was a game-changer for me,” said Narayanan, 54, who returned to India in late 1986.

Today, Narayanan is managing director of Vinyas Innovative Technologies Pvt Ltd., a group of global electronics manufacturing companies that together generate more than $100 million in annual revenues.

Based in Mysore, India, Vinyas has become a corporate champion of employing the disabled. Since 2007, the privately held company has dedicated itself to training and hiring at least two people a year who are either hearing impaired or have a mental disability. Today, more than 10 percent of Vinyas’ global workforce of 1,000 employees is disabled. Of those workers, 80 are hearing impaired, 14 are mentally challenged and 10 have other disabilities.

Creating work opportunities for the disabled is a mission Narayanan said was reinforced during his years at USC when he realized firsthand the value of putting in an honest day’s work. But the roots of that mission go back to his childhood.

“My father was a psychiatrist and research scholar who did a lot of work with the mentally challenged,” said Narayanan, who was born in Bangalore and earned his undergraduate degree from Bangalore University in 1981. “He would always come home from work and tell me, ‘If these people could work in a “normal” environment it would definitely make a difference in their lives, but that opportunity is not available to them.’”

When he launched Vinyas in 2001, Narayanan made it a priority to create work opportunities for the disabled. Prior to forming Vinyas, he established an electronics manufacturing services company for an industrial group in Mysore.

Working with local schools for the disabled, Vinyas developed a training program for potential employees. And the company prodded some of its supervisors to learn sign language.

“It’s not been difficult at all,” Narayanan said of the extra investment in time and money required to hire the disabled.

The employees perform such tasks as assembling electronic boards and packaging items. They include workers like Puttaraju, 28, who is hearing impaired.

“I like the environment and working culture,” said Puttaraju, who requested that only his first name be used. “My supervisors always encourage and support me to do very well in my job.”

Another hearing-impaired employee, Ramachandra, 27, has worked in the Quality Department from four years.

“I feel to be proud working at Vinyas,” said Ramachandra, who also declined to give his last name.

One mentally challenged employee works in the front office at Vinyas.

“He can communicate well,” Narayanan said, “but he doesn’t know how to lie. If I say, ‘Tell that visitor I am not here,’ he will say, ‘Narendra said he is not here—he’s right here, but he says he’s not.’’’

But not being able to lie is the whole point, Narayanan added. “The reason we put him in the front office is to make the point that your business should be honest and ethical, and it all should start when customers walk into your door.”

Most of the disabled employees at Vinyas are in their 20s and 30s. When the program started in 2007, they mostly kept to themselves, Narayanan said, but over time they’ve become integrated with the whole workforce.

“They eat with everyone and have friends throughout the company,” Narayanan said.

He has seen other changes in the group as well.

“When they started, most would not be able to correlate what 100 rupees ($1.60) would get them, or that they should not spend all of their 6,000 rupees ($95) on food,” Narayanan said. “One young man who at first didn’t know what to do with his money went to HR one day after working here for a few years and said, ‘Hey, I worked on this particular Sunday and was not paid for it.’ This is an example of the changes I have seen in them.”

Narayanan’s commitment to the disabled has earned his company accolades in his native country. India’s Ministry of Social Justice and Welfare named Vinyas “Best Employer” for the Year 2010–11. Through his involvement with Rotary International, Narayanan has been successful in encouraging other companies in India to follow his lead. And this past summer, Narayanan was recognized with a Widney House Volunteer Award from USC.

Indeed, Narayanan visits Southern California every six months or so as a board member of an Indian-run company based in Los Angeles. When he does, he makes sure to look up his old friends at USC—the ones he credits with transforming a once-shy kid from India into a socially conscious entrepreneur. “I really came out of my shell there,” he said.