What Price, The Moon?

Like most professionals of a certain age, Joseph R. “Joe” Gutheinz Jr. is mulling retirement.

And, like many soon-to-be retirees, the Houston-area defense and family law attorney has travel on his mind. Gutheinz and his wife, Lori Ann, plan to visit Spain, Romania, Cyprus and Malta, among other places.

But they don’t plan on bringing home any ordinary souvenirs. Instead, they hope to include in their luggage some items that Gutheinz has been obsessed with for 25 years, dating back to when he was a special agent at NASA: moon rocks.

Square-jawed, with a salt-and-pepper beard and a steady gaze that means all business, Gutheinz isn’t on a fool’s quest. He is, after all, unofficially known as the “moon rock hunter,” a moniker bestowed on him by numerous media outlets that have reported on a unique and fruitful mission that began in 1998 with a case he ran called Operation Lunar Eclipse.

Gutheinz, who earned a master’s degree in systems management in 1984 from what was then known as the USC School of Engineering, had no clue his studies at USC would come in handy hunting down missing or stolen moon rocks that were collected by American astronauts between 1969 and 1972 on the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17 missions.

The precious goods from outer space — about 842 pounds of lunar rock, ranging from dust particles to pebbles — were gifted by the Nixon and Ford administrations to U.S. states, territories, the United Nations and foreign governments.

The problem is, NASA didn’t keep any records of the moon rocks given away after 1973. Scores of the 377 moon rocks doled out by the Nixon and Ford administrations went missing. Some recipients forgot they even had them. Some, Gutheinz later learned, ended up in desks, a shoe box, a garage, a pocket. Others were stolen, fetching some $5 million on the black market.

For a law-and-order guy like Gutheinz, that didn’t sit right.

“I once met this astronaut,” said Gutheinz, whose experiences hunting down moon rocks could be ripped from spy novels. “The astronaut told me that when he was a kid, he always wanted to be a pilot. He went to a museum and saw a moon rock. The experience made him decide he wanted to become an astronaut, not just a pilot.”

He added, “There are probably kids in Kenya or Singapore or wherever that might be inspired to become an astronaut after seeing something that was brought back from space by man and put in a museum.

“Part of the reason I’m put off by people who steal moon rocks is because they’re stealing dreams from children.”

The Value of a USC degree

A military brat, Gutheinz, born at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, N.C. While attending Fallbrook High School in California, he managed to earn two degrees in 1975 from Monterey Peninsula College: an associate of arts degree in liberal arts and sciences and another in administration of justice. Three years later, he earned a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice with a concentration in public administration from Cal State University Sacramento, followed by a master’s degree, in 1979, in criminal justice.

In 1980, Gutheinz completed the bulk of his studies toward a Ph.D. in sociology at UC Davis before being called up to active duty in the army.

He worked on his systems management degree from USC while he was an army intelligence officer in Germany and finished his studies at Fort Rucker in Alabama in 1984 while also earning his army aviator wings. With a concentration in logistics, he learned how to track inventory from one point to another and look for anomalies.

“I thought my USC degree would serve me well in government work,” Gutheinz explained. “When an item becomes missing, you need to know how to review the chain of custody to focus on a date and time of loss and, most importantly, a responsible party.”

Over a 20-year period beginning in 1979, Gutheinz worked as an army officer and special agent for three federal agencies; in addition to NASA and the Department of Transportation, he was an investigator for the Federal Aviation Administration. Although he is known for investigating stolen or missing moon rocks, he headed up several other complex investigations, particularly while working as a special agent for NASA’s Office of Inspector General. His job was to go after contractors that were bilking the agency.

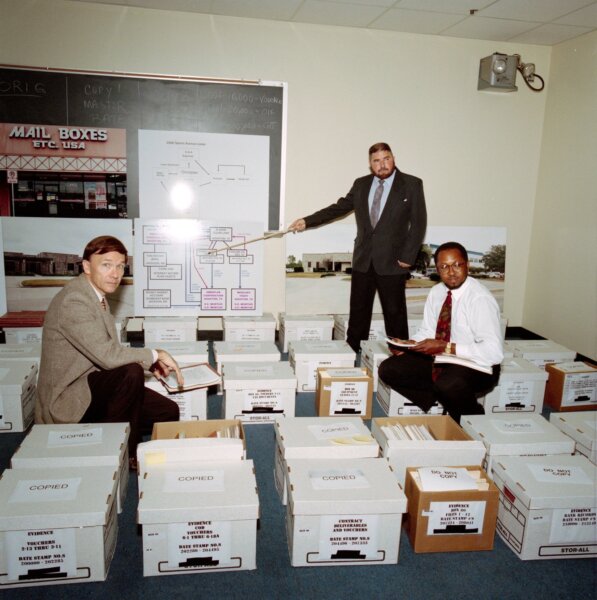

One of his biggest cases involved a now-defunct subcontractor of Rockwell Space Operations Co., once a prime contractor for NASA’s space shuttle and space station. The owner of that subcontractor, Omniplan, pleaded guilty to about 180 criminal counts of fraud in 1996, and was sentenced to two years in federal prison and ordered to pay nearly $12 million in fines and restitution. In addition, seven of his companies were ordered liquidated, five after receiving felony convictions.

But the topic of moon rocks really gets Gutheinz’s pulse racing — notably, Operation Lunar Eclipse. The nationwide sting operation was aimed at shutting down the bogus moon rock trade.

‘Hello, Joe. This is Ross Perot’

As part of Operation Lunar Eclipse, which included a partner at the U.S. Postal Service, inspector Bob Creggar, and U.S. Customs, Gutheinz met with a shady moon rock dealer in a seafood restaurant in Miami. He got a key assist on the case from billionaire H. Ross Perot, and he used a wise guy pseudonym borrowed from when he was going after actual mobsters while working undercover on a 1989 case for the Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General.

In a real-life scenario that could have been pulled from a crime thriller novel, Gutheinz placed an ad in a national newspaper soliciting moon rocks from a fictitious company, John’s Estate Sales, whose phone number was connected to a recorder on a desk in a closet off Gutheinz’s NASA office. An individual claiming to have a moon rock agreed to meet with Gutheinz —aka mobster Tony Coriasso — and an associate at Tuna’s restaurant in North Miami. With Gutheinz was Creggar, aka John Marta, allegedly a representative for a wealthy buyer.

The seller claimed to have 1.142 grams of lunar rock and a 10-by-14-inch wooden plaque given by the Nixon administration to the government of Honduras after the final Apollo mission in 1972. The asking price was $5 million.

After NASA and other federal agencies dragged their feet in coming up with the $5 million, Gutheinz had an idea.

“I wondered if Ross Perot would do it,” he recalled. “He went to Annapolis, was pro-military and was a true patriot.”

Gutheinz cold-called Perot’s office and was stunned to get through to his personal secretary. He explained briefly how he was hoping to get Perot’s help in finding stolen moon rocks.

“Twenty seconds later,” he said, “my phone rang.”

He picked it up.

“Special Agent Joe Gutheinz.”

“Hello, Joe. This is Ross Perot. How can I help you?”

“We’re trying to get back an Apollo moon rock in a sting operation and we’re hoping you’ll put up $5 million.”

“No problem.”

Recalled Gutheinz: “That was it. It was like he was buying a cup of coffee.”

Perot wired the $5 million into an account and even got the vice president of the bank to pen a letter confirming the funds were there.

After two months of negotiations, the seller said the moon rock was in a vault in Miami. In fact, the moon rock was seized under warrant in the vault and the plaque it had once been affixed to was found in the trunk of the seller’s car.

The plaque was turned over to NASA and eventually returned to Honduras.

Students enlisted in quest

Operation Lunar Eclipse revealed that other moon rocks were missing and might have slipped onto the black market. Considered national treasures, moon rocks cannot be legally sold.

So, after retiring from NASA in 2000 to focus on his law practice (Gutheinz earned his law degree from South Texas College of Law in 1996), the man who eventually would be dubbed the “moon rock hunter” continued his quirky quest.

While teaching an online class in investigative police techniques for criminal justice graduate students at the University of Phoenix, Gutheinz recruited his students to hunt for moon rocks.

“It was a safe way of teaching my students how to conduct a real investigation,” he said. “And I didn’t have to worry about them being harmed or getting whacked.”

Over the next decade, about a thousand of Gutheinz’s students helped find 78 Apollo era moon rocks, including three taken home by U.S. governors, and 48 given to states. (Still missing are those awarded to Delaware and New York.) About 160 Apollo era lunar rocks still are unaccounted for, stolen or lost, Gutheinz says.

When he retires, he’ll turn over control of his law practice to his two sons, Michael and James, both U.S. Army veterans and partners in the firm. Then he and his wife will start booking those international flights.

“I believe these moon rocks can be found and that I can find them,” declared Gutheinz, who above all his college degrees cherishes his USC one the most. “My USC degree is something I hold very dear.”

Even, perhaps, more than lunar dust.