Riding the Wave

It’s the quintessential Southern California day, 72 degrees and sunny. You’re on a surfboard, paddling through the calm waves, the ocean an azure blue. Palm trees sway in the distance. Birds chirp. Your hand slices through the glistening water. You feel a light breeze, the gentle sway of the board. You’re centered; at peace.

Then you hear a voice: “We added pods of dolphins somewhere in the ocean. They’re a bit tricky to find.” You snap back to reality and take off your headset.

You’re not paddling in the Pacific. You’re in a basement lab at USC’s Health Sciences Campus, surrounded by a team of neuroscience, biokinesiology and computer science researchers, and this is a virtual reality surfing simulator.

Designed to probe how ocean surfing therapy might help relieve chronic pain, the project is led by Jason Kutch, an associate professor of biokinesiology, and Heather Culbertson, assistant professor of computer science.

“At least a couple of people have described it as one of the most immersive VR experiences they’ve ever encountered,” said Kutch, who leads the USC Applied Movement and Pain Laboratory. “A very immersive therapy like this can have a big impact on a person’s pain experience.”

A fully immersive experience

Surf therapy is being explored as a complementary approach to managing chronic pain, which affects some 50 million Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scientists believe it could also effectively treat a number of mental health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression and stress.

But despite its promise, most people don’t have the ocean at their doorstep. Kutch, who himself found relief from chronic pelvic pain in surfing, wanted to know if a VR surfing experience provide some of the benefits of the real thing.

To find out, last fall, he teamed up with Culbertson, an expert in haptic technology who leads USC’s Haptics Robotic and Virtual Interaction Lab, and James Finley, associate professor of biokinesiology and physical therapy.

“Our goal is to engineer a virtual reality simulator detailed enough to replicate surfing’s benefits,” said Culbertson. “We’re not trying to gamify the experience. It’s a fully immersive kind of calming experience that allows users to get that ‘surfer’s high.’”

Crucially, the setup allows the team to test the most therapeutic aspects of surfing on the ocean. Which part of surfing brings pain relief?

“Is it the feel of being out on the ocean? The sounds and smells of the environment? The adrenaline rush that comes with catching a wave?” Culbertson asked. “I am interested to see how far we can push the realism and immersiveness of the system.”

A safe place

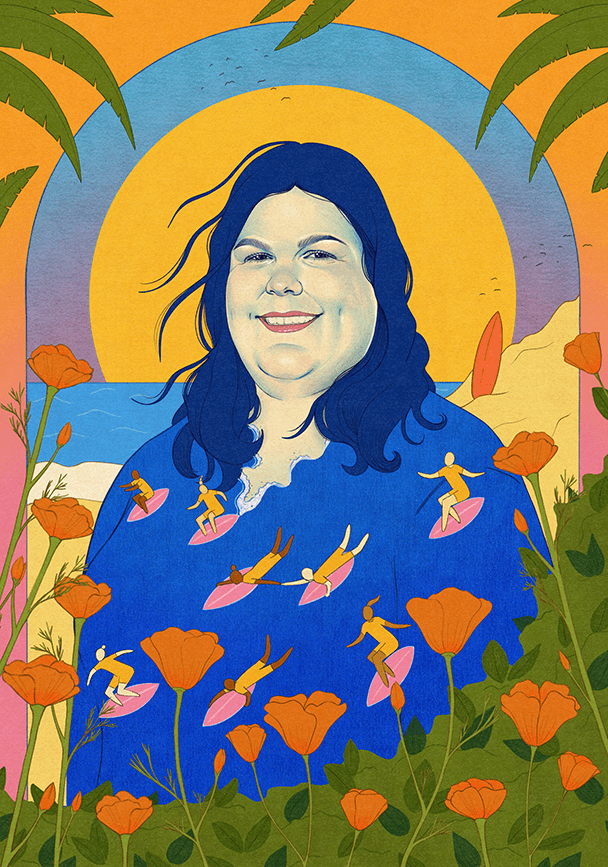

Study participant Christina Tolle (45), a clinical trial manager from San Diego, has suffered from chronic pain related to severe endometriosis and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a connective tissue disorder, for more than 20 years. “To get in the water and have a safe place to start surfing again, I knew that would be helpful to me,” said Tolle, whose pain forced her to quit her surfing hobby more than a decade ago.

“My intention throughout the entire process was to be in the moment, feel what was going on in my body, and not disconnect from it, which was something that I had been doing for years because of the pain.”

Last September, Tolle took part in the research team’s first study, testing the effects of surfing on 10 chronic pain patients by measuring their brain activity before and after a surf session. When the results came in, the researchers were pleasantly surprised.

“We saw a really positive jump in alpha band activity, which is a good measure of how relaxed someone is and overall positive mental state,” Kutch said.

Next, the researchers started working on recreating the experience in virtual reality. The team rigged a surfboard to a motion platform simulator that you might see at an amusement park. Computer science doctoral student Premankur Banerjee developed motion platform hardware to simulate the sensation of waves, seamlessly integrating it with VR visuals using a complex technique known as motion mapping. Participants can sit, kneel, or stand on the board wearing a headset. They can surf, paddle, row—even go underwater.

A VR novice, Tolle admits to being a little skeptical about the virtual experience at first. Could it really come close to matching the calm and exhilaration of being in the ocean, connecting with nature?

“They hooked me up to the harness and I got on the board,” she recalls. “And it really did feel the same as getting onto a hard board in the water. I was actually able to disconnect from the fact that I was in the basement of a building with no windows and engage in what the VR was showing me. The ocean, the island, the beach; it was incredibly realistic.”

In the next phase of the study, participants will test the system in the lab to see if the pain reduction outcome can be replicated in VR. From Tolle’s perspective? It worked.

“I felt significantly better after my VR portion,” said Tolle. “Being in the car for more than an hour always ramps up my pelvic pain. When I left the lab after trying the VR simulation, my pelvic pain was significantly decreased. Even after a long drive, I had less pain when I got home and the next day.”

Surf’s up

“The VR system has hand tracking, so it’s replicating what I’m doing in real life,” said Jason Cherin, a biokinesiology doctoral student, as he paddled past a sunken pirate ship. “We’ve created this very peaceful Paradise Island-type environment, with palm trees, beautiful skies, birds off in the distance.”

To simulate the feeling of consistent forward movement on the board, the team used some “perceptual trickery” with acceleration. The board slides forward, and then imperceptibly slides back, simulating the feeling of constant forward acceleration. In reality, it is moving forward less than a foot each time.

For Culbertson, whose lab has previously tackled haptic touch and virtual textures, this project means venturing into uncharted waters.

“It’s haptics at a scale that I never done before,” Culbertson said. “My lab focuses a lot on wearable haptics, so, haptics on a very small part of the body. At this scale, there are so many components and so many senses to integrate, which makes it a really complex but enjoyable challenge.”

The team is now assembling a safety system to help people hop to their feet on the board. Force sensors under the board will allow the system to recognize where the person is standing to “get into the dynamic flow of surfing,” said Culbertson. Next up: gloves to improve tactile realism, adding a fresh ocean smell, even mist.

While chronic pain is the diving-off point for this research, Kutch said the findings could help with the development of other therapeutic programs, including ones for children with autism spectrum disorder.

“The main point is that we can expand access to therapy. Not everyone is fortunate enough to live right at the ocean,” he said. “We want to have this kind of bridge where there’s this immersive activity that can be adapted to a person’s capabilities. They can still experience some of the benefits of this rich, dynamic environment, and we can adapt it to their needs.”

For Tolle, who hopes to take part in future studies, the message is simple: “I really think that this technology has a huge potential to change people’s lives.”