Organizing Chaos

Data is essential to the work scientists and researchers do every day, but organized haphazardly, navigating it can be cumbersome at best, dysfunctional at worst.

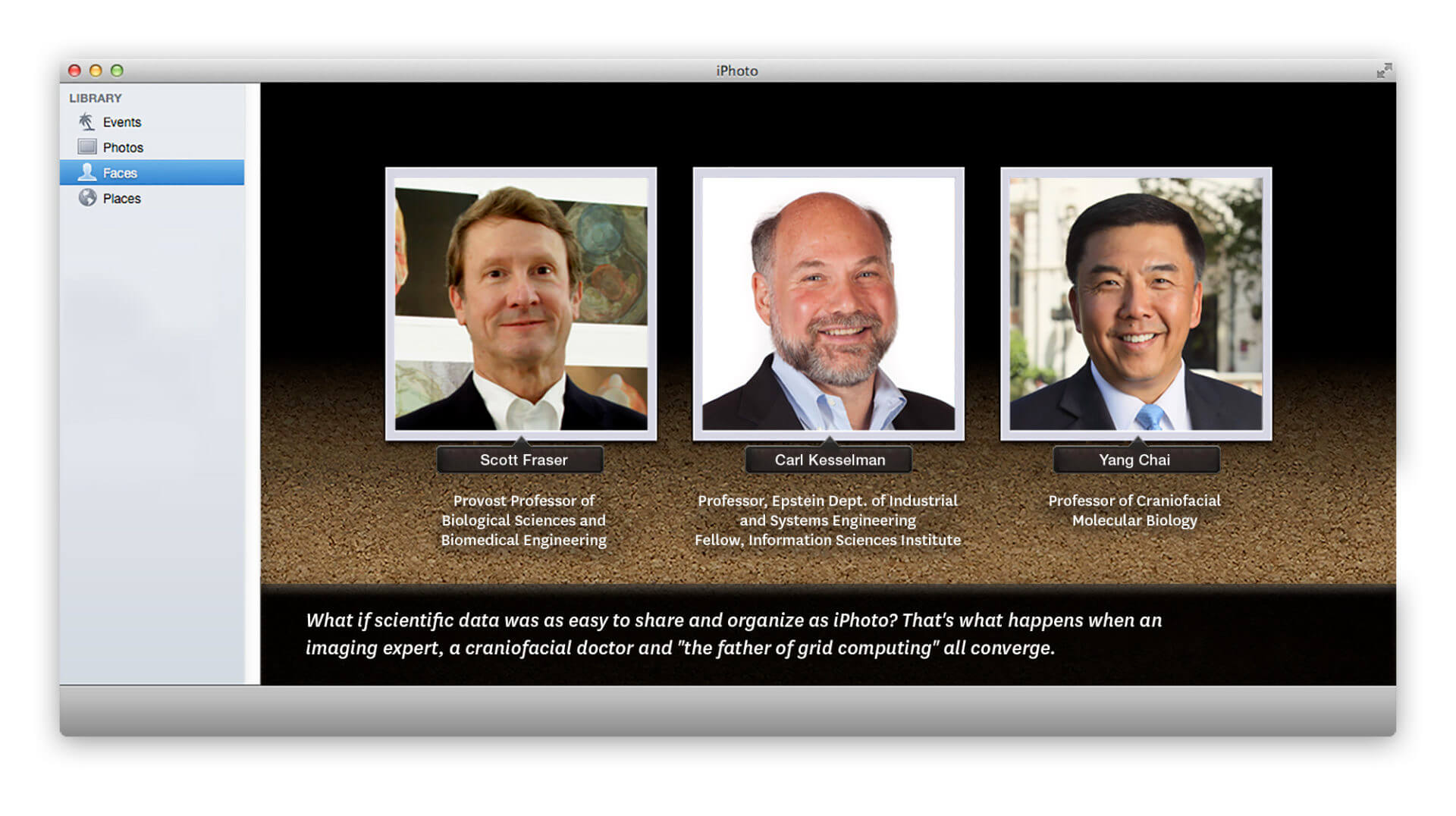

But with a five-year, $10 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), USC Viterbi Information Sciences Institute Fellow Carl Kesselman and his team have come up with ways of making scientific data easy to upload, organize, share and—perhaps most importantly—navigate.

The FaceBase grant from NIH is aimed at advancing craniofacial research by coming up with ways to better organize datasets on development and deformities in the face and brain so doctors, surgeons and researchers can easily access and study the information.

Kesselman has created one such solution with a database for information like gene expressions of molecules and tissues, as well as other aspects of how the face forms, with an easy-to-navigate labeling and organizing system he likens to iPhoto. Kesselman’s team is the hub that interacts with about a dozen spoke projects from universities across the country that provide data to the platform, Craniofacial Central.

“Scientists can spend up to half their time just trying to move their data and around and figure out what they have and keep track of it,” Kesselman said. “We want to make searching for data as easy as it is to get pictures off your smartphone to share, organize and access them.”

USC Dornsife and Viterbi’s Translation Imaging Center Director Scott Fraser worked alongside Kesselman to secure the grant, seeing an opportunity to address a big problem.

“I have friends in the legal business, and every once in a while they’ll archive huge boxes of file folders and I wonder, Will anyone ever open those boxes again?” Fraser said. “Imagine that was scientific data that no one knows how to find or interact with. The last thing you want to do is go through it page by page to find what you want.”

Fraser’s lab builds powerful microscopes that can capture images of facial cell formation much deeper and faster than such instruments could even just a few years ago, which is hugely beneficial to craniofacial research but poses challenges as well.

“As imaging techniques have gotten better, we have this exploding ability to collect data,” Fraser said. “And our ability to analyze or interact with that data hasn’t kept pace.”

Until now. With the Craniofacial Central database, Fraser has a whole new infrastructure for working with the data he’s collected. And he finds collaborating with others on the information that much easier.

“Those tools will impact so many researchers and allow us to better understand the data we’re collecting, and I think will be generalized to other fields as well,” Fraser said.

The dental field in particular will see huge benefits. Yang Chai, director of the Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology and associate dean of research at the Ostrow School of Dentistry, advises Kesselman on the hub and oversees one of the hub’s contributing spoke projects. Chai’s team works on craniofacial development and examines birth defects like cleft palates.

Chai said the hub “will not only impact what craniofacial researchers do, but will set us apart as a model for others to follow in research for the kidney and brain.”

By bringing together the USC Viterbi, USC Dornsife and USC Ostrow schools, Kesselman said they can tackle different aspects of problems in craniofacial research in ways that wouldn’t be possible in many institutions.

“My interest is in finding new and innovative ways that information technology and informatics can be used to advance science,” Kesselman said. “FaceBase is an example of a really wonderful application where we can work very closely with this research community on problems. And if solutions are found, they can radically improve people’s lives.”

And many are enthusiastic.

“It’s an amazing Viterbi success story,” Fraser said. “Carl is creating tools that are making a big impact in biology and biomedical work, and I think he’s going to take over the world.”