Teleporter for Justice

Cheyenne Gaima’s superpower of choice: teleportation, an imaginary means of instantly traveling from one place to another.

The USC Viterbi senior in computer science obviously doesn’t possess this magical, Star Trek-like ability. However, Gaima has seen much of the world in her 21 years, having lived on two continents and on both the East and West Coasts of this country. Place has played a profound role in her life, both shaping and being shaped by her.

Wherever Gaima has gone, she has left an indelible impression: as a child in Cameroon, as the founder of a coding program for girls in Maryland, as a leader of the USC chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers, or as a peaceful protestor at marches in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., demonstrating against police brutality and institutional racism. One of USC Viterbi’s strongest voices against the marginalization of African Americans, women and other underrepresented groups, especially in technology, Gaima envisions contributing to the creation of a more just society that taps the collective talents of all its members.

“The voice of students in equity and inclusion work is very important,” said Brandi Jones, USC Viterbi’s vice dean for diversity and strategic initiatives and a NSBE advisor. “USC Viterbi considers Cheyenne Gaima to be a leading voice and thought partner in our efforts to address persistent disparities and improve the student experience.”

The following is a snapshot of Gaima’s life seen through the lenses of geography and time.

Chapter I: Douala, Cameroon

Born in United States, Cheyenne Gaima lived in Cameroon between the ages of 2 and 5. Her parents, both immigrants to the U.S. from that African nation, sent Gaima, her younger brother Stanley, and her older brother Kenneth Tatah there so they could “grow up traditionally” for a few years. At the time, her father, Stanley Oben, an information technology specialist, and mother, Assumpta Bourgeois, a nurse, were putting in 12-hour-plus workdays to gain a foothold in their respective careers, and thought their children would fare better among so many loving grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins than in American daycare.

Gaima fondly remembers playing soccer on unpaved dirt roads, fetching water from a well and carrying it back home with a bucket on her head. Sometimes she would race her cousins to see who could run the fastest and farthest without spilling. It was a good life, devoid of racism and classism. “We provided for each other and looked out for each other, so while we were poor, we were good,” she said.

Upon returning to the U.S. for kindergarten, though, Gaima had her first experience feeling like the other. Although Gaima spoke English, her first language, fluently, her thick accent — and perhaps her dark skin — led administrators to place her in a class for non-native speakers. Although teachers treated her and her immigrant classmates fairly well, Gaima recalls longingly watching other students play together in the main classroom and read Dr. Seuss books without an accent.

“My empathy for immigrants and subsequently people of color began there,” she said. “I felt bad for being excluded from my peers for supposedly not being able to speak English at a certain level, and even worse for my ESL classmates who struggled more than I did because their second language truly was English.”

On the upside, Gaima quickly realized that in America she had educational and professional opportunities not readily available to her and others in economically underdeveloped Cameroon. “I’m absolutely milking every single opportunity that comes my way here,” said Gaima, a first-generation college student who interned at Facebook three consecutive summers. In August, she became the new president of National Society of Black Engineers.

As much as Gaima loves America and all it has offered her and her parents, she hopes one day to return to Cameroon. In her vision, she will graduate from USC Viterbi, succeed in a STEM-related endeavor and then make a pilgrimage to west-central Africa.

“I need to be there,” Gaima said. “I don’t know how it’s going to happen. I don’t know when it’s going to happen. But when I’m older and I have the resources, I’m going to be in Cameroon and take care of my family and help the lives of marginalized people there.”

Chapter II: Lockheed Martin in Washington, D.C.

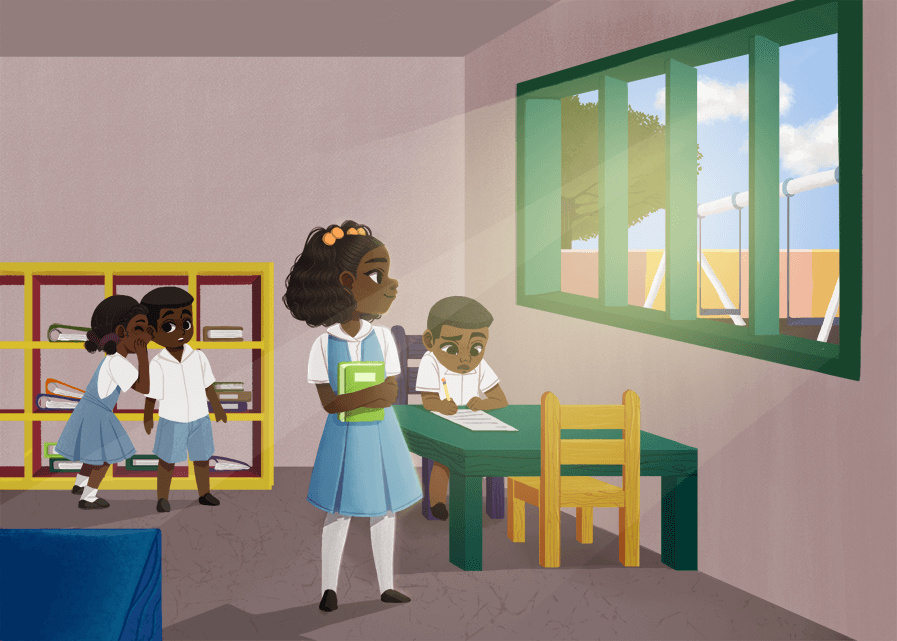

Like far too many economically disadvantaged children of color, Cheyenne Gaima had limited exposure to technology in her elementary, junior high and high schools. Her high school offered relatively few computer science courses, so she was thrilled when she was chosen as one of only 20 girls to spend the summer before her junior year learning about technology and computer science in Girls Who Code, or GWC, a nonprofit that aims to increase the number of women in computer science through hands-on training

For seven weeks, Gaima took two buses from her home in Silver Spring, Maryland, to Lockheed Martin in Washington, D.C. The free program was transformational: In addition to acquiring rudimentary computer skills, Gaima said she and the other girls learned to take risks, embrace failure as a speedbump on the road to success, and have the courage to ask for help — important qualities to thrive in the male-dominated world of STEM.

“Girls Who Code quite literally changed my entire life. It changed my perspective on what was possible for me, and it opened up an entirely new world that I wasn’t even aware of prior to participating in the program,” Gaima said. “I became a version of myself that I really liked and wanted to get to know more — one that was bold, creative, thought wild ideas and was eager to execute them. Someone who saw her potential as infinite.”

Ever the innovator, Gaima decided to pay it forward. Disappointed by the paucity of STEM courses offered by local junior high and elementary schools, Gaima founded CodeIT, which she modeled after Girls Who Code. “I decided that I wanted to offer a similar opportunity to younger girls in my community to get exposed to computer science and build this community of sisters that they could learn from and grow with,” she said.

CodeIT initially held meetings in public libraries, the basement of a church and a school cafeteria, bringing together volunteer high school girls with a background in computer science and elementary and junior high students interested in technology. CodeIT became so popular under Gaima’s leadership that it expanded beyond her school district to include students from Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. More than 150 girls have gone through the free afterschool and summer program since its inception in 2016.

Even though Gaima turned over CodeIT’s operations to others after high school, she remains involved, delivering the program’s welcome address to participants.

“I think that it’s important to have girls be able to see themselves in any position that they desire,” she said. “Whether that’s engineering, medicine, astronautics — I don’t want girls to ever think that the thing that’s holding them back from achieving anything and everything that they want is their gender or gender identification.”

Chapter III: Center for Engineering Diversity

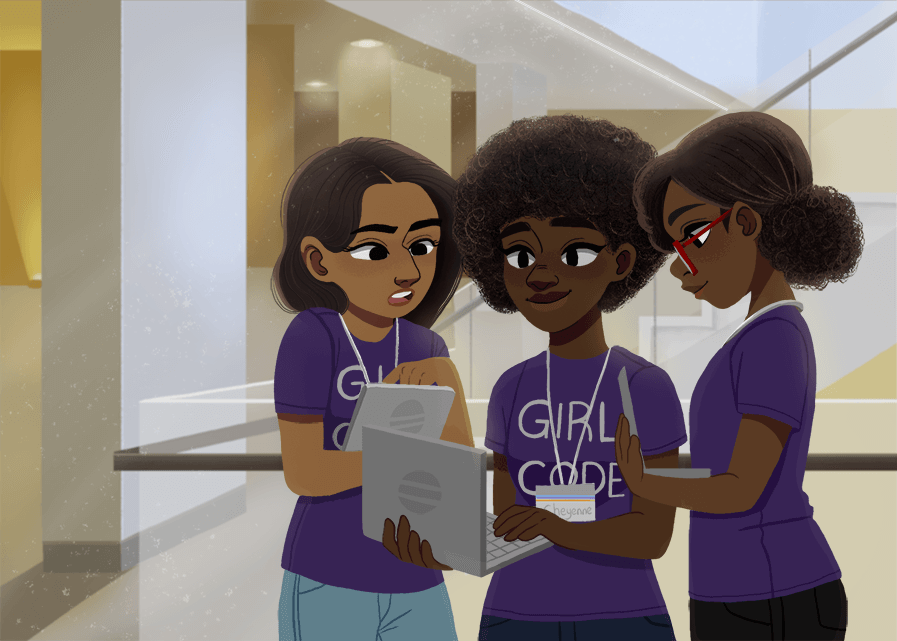

In the spring semester of her freshman year at USC Viterbi, Cheyenne Gaima and six other students got together to study for their discrete mathematics final. At some point, people began sharing their summer plans. When Gaima proudly said she had landed an internship at Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, her roommate’s white boyfriend chimed in with a remark that literally left her speechless.

“Oh, she only got that cause she’s a Black girl,” he said.

After five seconds of uncomfortable silence, Gaima gathered her things, wished everybody good luck on the test and retreated alone to her dorm room. Although she had experienced racism before, Gaima had expected USC to provide a safe haven. When, much to her disappointment, it hadn’t, she began thinking about the need to connect with her roots.

“This was the defining moment at USC when I realized, damn, I need more Black friends and Black engineering peers,” Gaima said. “To make it in this major at USC, I knew I needed positive, uplifting support from people who get it. Even more, I wanted to give that support to other people who may have naysayers in their ear as well.”

Gaima found her home away from home in the National Society of Black Engineers. One of the largest student-run organizations in the country, NSBE is committed to increasing the number of Black engineers who positively impact the community. In 2018, Gaima and her fellow NSBE members at USC were named the Regional and National Chapter of the Year. The chapter has taken home a raft of awards since then, including first place in the regional Academic Tech Bowl in 2019 and the KIUEL Choice Award: Event of the Year for 2019–2020.

Gaima has made important contributions to NSBE’s success. As the programming and events chair from 2019 to 2020, she helped boost event attendance by 23% by adding new activities such as movie nights and a Halloween party co-sponsored with the Society of Hispanic Engineers. Higher event participation, she said, often translates into increased membership. To help NSBE members professionally, Gaima organized mock job interviews for seniors and even assisted with the writing of cover letters.

“Cheyenne has made the environment within USC NSBE fun and easy to engage in. I feel uplifted by her,” said Kenya Foster, NSBE’s current programming and events chair, a junior studying astronautical engineering with a minor in astronomy. “I feel encouraged to continue to pursue engineering and the difficult coursework because of the paths that people like Cheyenne have blazed and the support they have given along the way.”

As USC’s NSBE chapter new president, Gaima plans to meet with every Black USC Viterbi first-year student, either in person or via Zoom, to make them aware of the organization and what it has to offer.

“Finding a group of people that you relate to, can confide in and can be yourself around is important for any college student, but especially for students in a field and a school where there is scarcity of people that look like them,” Gaima said.

Gaima believes that having more diversity in engineering would benefit both the field itself and society at large. Algorithms and big data in several fields, including advertising, insurance and policing, are often inherently sexist and racist, she said. Such was the case in 2018 when Amazon.com had to junk an algorithm it was testing as a recruiting tool that favored men over women. The problem, according to Reuters: Amazon computer scientists had trained the AI on data submitted by applicants over a decade, much of which came from men. Engineers from underrepresented groups might have helped flag such bias earlier in the process, Gaima said. More Black, women, Native American and Latinx engineers would also fuel innovation.

“An inclusive society where all people are respected, valued and empowered is one that is safer, more advanced, and a society that is worth living in,” Gaima said. “To live in a world where race, gender, class, religion and so on could not limit you from living the life that you want to live, would allow us to solve bigger problems and make more important discoveries by bringing different perspectives to the table.”

Chapter IV: Georgetown, Washington, D.C.

It wasn’t Gaima’s first protest, but it might have been her most important.

On May 30, just five days after the death of George Floyd — a Black man killed by a white police officer by kneeling on his neck for nearly nine minutes — Cheyenne Gaima joined a multicultural march in downtown Los Angeles. Gaima said she came at the invitation of a friend who had been shot by a rubber bullet in a demonstration the night before.

For a brief moment, Gaima hesitated. After all, the COVID-19 pandemic still raged, and she had spent the past 68 days dutifully social distancing, venturing from home only to walk her dog or shop for groceries. But this felt different. Gaima said she needed to join the growing social movement against police brutality and systemic racism to release the deep wellspring of emotion inside her. So she donned a face mask and walked out her front door.

“I had to healthily express all of the rage, frustration, fatigue and hunger for change I was feeling,” Gaima said. “And where better than with the people on the streets. The moment felt so fresh. I knew I had to go out.”

Back home in Silver Spring, Gaima joined a large march on June 13 in the nation’s capital. Surrounded by thousands of peaceful activists representing a rainbow of races, ethnicities and sexual orientations, Gaima carried a sign that read, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” a line popularized by Audre Lorde, the late African American writer, feminist and civil rights activist.

As in Los Angeles, the protest felt different. “I think there was a very collective feeling among everyone who was protesting — Black, Indigenous, people of color, white, trans, disabled, you name it — that overpowered the fear, the fatigue, the frustration. It was hope,” she said. “For the first time while I was out there, I really, truly felt like change was coming. It was really just a matter of time.”

Protests alone, no matter how raucous and righteous, won’t end police brutality, racism and injustice, Gaima said. However, they can act as a catalyst by starting conversations and sparking legislation.

Enduring change, she added, will only occur with the creation of political “mutual aid projects” in which people coalesce around specific issues to protect society’s most vulnerable. Real-life examples include saving the lives of undocumented immigrants illegally crossing the border by leaving food, water and supplies in the harsh desert, or activists opening their homes to released prisoners or children coming out of the foster care system.

Equally important, Gaima said, is having “more people that are representative of the country in power: more people of color, more women, more people with disabilities.”

With aspirations to earn a joint law degree and MBA and to one day “lead,” perhaps Cheyenne Gaima will become such a future change agent.

Chapter V: The Galen Center, Los Angeles (2021)

“So you say you can’t breathe

Can’t breathe like an asthma attack

No…can’t breathe like something’s caught in your—

You know when you forget to break the noodles? And you’re eating ’em and one just gets stuck”

— “I Am Not A Murderer” by Cheyenne Gaima

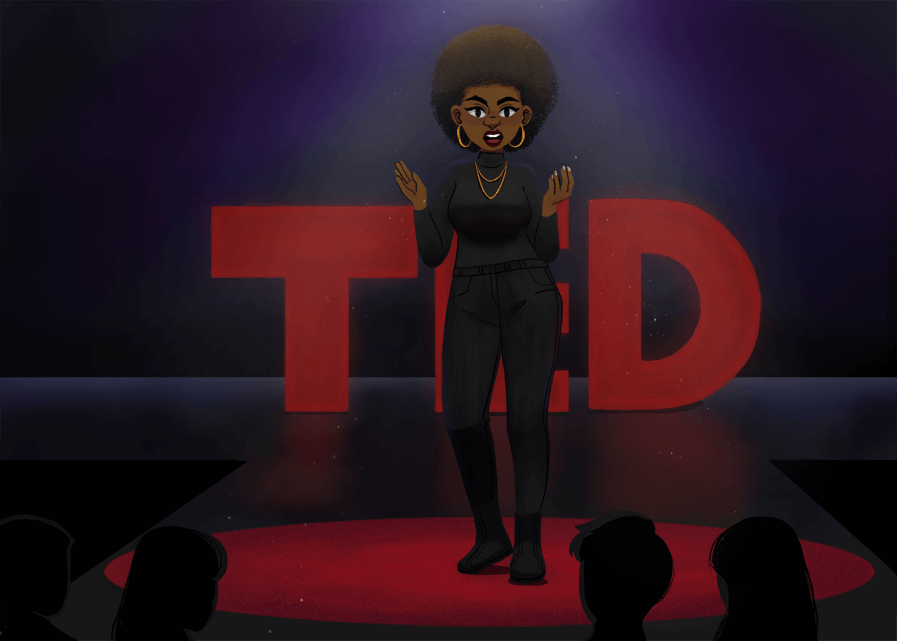

Cheyenne Gaima has a dream: In 2021, after she graduates from USC Viterbi, she will give a TEDx talk from the stage of the Galen Center before a rapt audience of thousands of Trojan students, faculty members and alumni. For the occasion, Gaima would don black jeans, a black turtleneck, black boots, gold hoop earrings, gold chains, long nails and a big Afro. “I’d want my Black Panther look, channeling my inner Angela Davis,” she said, referring to the African America political activist and Marxist feminist.

The topic: Police brutality against Black people in America and how to stop it.

For the first few minutes of her presentation, Gaima said she would recite “I Am Not A Murderer,” a poem she has written about the ever-lengthening list of Black men and women unjustly killed by police. When she said a name, say, Eric Garner for instance, she would act out how he died — in his case, a New York City police officer put Garner in an illegal chokehold in 2014 when arresting him. His crime: selling single cigarettes from packs without tax stamps. “I think reading their names is really jarring, really disturbing,” Gaima said. “They need to hear it.”

Audience members would also need to hear how America has normalized racism against Blacks and just how immoral and damaging that is, she added. They must recognize their privilege. “When the disproportionate killing of Black people by the police becomes a part of American culture, just like when mass shootings, the wage gap and criminal elected officials become a part of American culture, it gets mistaken for nature,” Gaima said. “And when something as horrific as racial inequity is seen as nature, or immutable, therein lies the problem.”

She would end her address with a call to action. Talk is cheap, Gaima would say. Taking tangible steps toward creating a more just society isn’t.

“What can you, as a USC student, faculty or staff member, mentor, athlete, professional, screenwriter, cook, musician, human being do to help level the playing field for our disadvantaged brothers and sisters so that we all may rise?” she would ask.

According to Gaima, the audience members, as well as non-Black and non-Indigenous Americans everywhere, must educate themselves about the Black experience in the U.S. That means reading books, attending plays, listening to music, visiting museums and seeing movies and TV shows that “chronicle the lives of Black people in the U.S. and others of the African diaspora,” she said. “Do your research! Work actively to unlearn the anti-Blackness that has been taught to us since our beginning days.”

Next, Gaima would tell the crowd that audience members in positions of power must make real sacrifice for the betterment of African Americans, even if doing so hurts.

“Advocate for the increased and strategic hiring of Black people and for the admission of Black students within your academic spaces,” she said. “Be the ‘radical’ person and speak out against anti-Black rhetoric and behavior, especially within your family and community. Call out your racist grandmother. The mindset changes that will take place in households are just as important as the structural and systemic changes that will take place outside of it.”

Finally, she would exhort everybody in the arena and beyond to spread the word about the importance of African American lives.

“Talk about how Black Lives Matter to everyone all the time. Don’t shut up about it,” Gaima said. “For the mere fact that the phrase must be repeated over and over for people to get it, just do it. Who knows? Maybe they’ll get sick and tired of hearing it and just accept it.”

Pivoting to the crowd a final time, Gaima would smile and deliver a final message.

“Thank you so much for being here tonight. Fight on!”