It’s the Year 2045. LA Is Powered by 100% Renewable Energy. How Did This Happen?

The year is 2045, and Kelly Sanders has never felt happier, or worked harder.

Sanders, the newly appointed dean of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, puts in long days balancing her administrative responsibilities with her ambitious research. On this hot, summer day, Sanders decides to duck out a bit early. She summons her self-driving electric car with an app on her cellphone. Five minutes later, Sanders’ Tesla picks her up.

Looking out the window, Sanders marvels at the near ubiquity of self-driving electric cars. Just 25 years ago, toxin-spewing gas guzzlers ruled the roads. No more. About four out of five vehicles now are electric, which has helped improve Los Angeles’ air quality. Because of self-driving cars’ ability to “talk” to one another to collectively identify the fastest and safest routes, traffic jams have largely become a thing of the past, even though the number of cars and buses has increased since the 2020s.

The Tesla enters the garage of her downtown condominium complex, stopping at a charging station powered by solar and wind energy. Arriving at her penthouse moments later, Sanders receives an alert on her cellphone. Opening an app that connects her appliances to the internet, she sees the follow-ing message: “Kelly, solar energy is abundant and cheap right now. You can run your dishwasher and washing machine for half of what it would cost you this evening.”

Sanders smiles and remotely turns on the dishwasher, which she leaves full for such occasions. Another notification tells her that the building’s solar panels — much smaller, more efficient and aesthetically pleasing than the big, clunky ones that once adorned nearby rooftops — have generated so much energy that some of it has automatically been sold to the power grid. Ka-ching!

Hungry, Sanders texts “Alfred” to prepare dinner. Her robotic assistant goes to the kitchen and begins cutting vegetables and slicing lab-grown chicken that it cooks in an electric wok. All of Sanders’ devices, including her water heater, stove, air conditioner, dishwasher, and washer and dryer, are powered by renewable electricity, just like nearly all appliances and buildings in Los Angeles.

Peering out her large bay window, she marvels at the beauty of the San Gabriel Mountains shimmering in the pristine twilight air. Air pollution has diminished in the region, saving lives and billions in health care costs.

Taking a swig of cold water — recycled, of course — Sanders thinks about how far we have come in such a short period of time. With a hint of pride, she also reflects on the role she and other USC professors played more than two decades earlier in contributing to a seminal report that helped move Los Angeles to 100% renewable energy and a brighter, cleaner future.

Toward a cleaner tomorrow

Toward a cleaner tomorrow

Los Angeles, filled with emission-producing cars and ports and factories powered by fossil fuels, has long held the dubious distinction as one of America’s most polluted cities. The American Lung Association recently gave Los Angeles County and its surrounding areas an F grade for particle and ozone pollution, which can lead to lung, heart and other health problems.

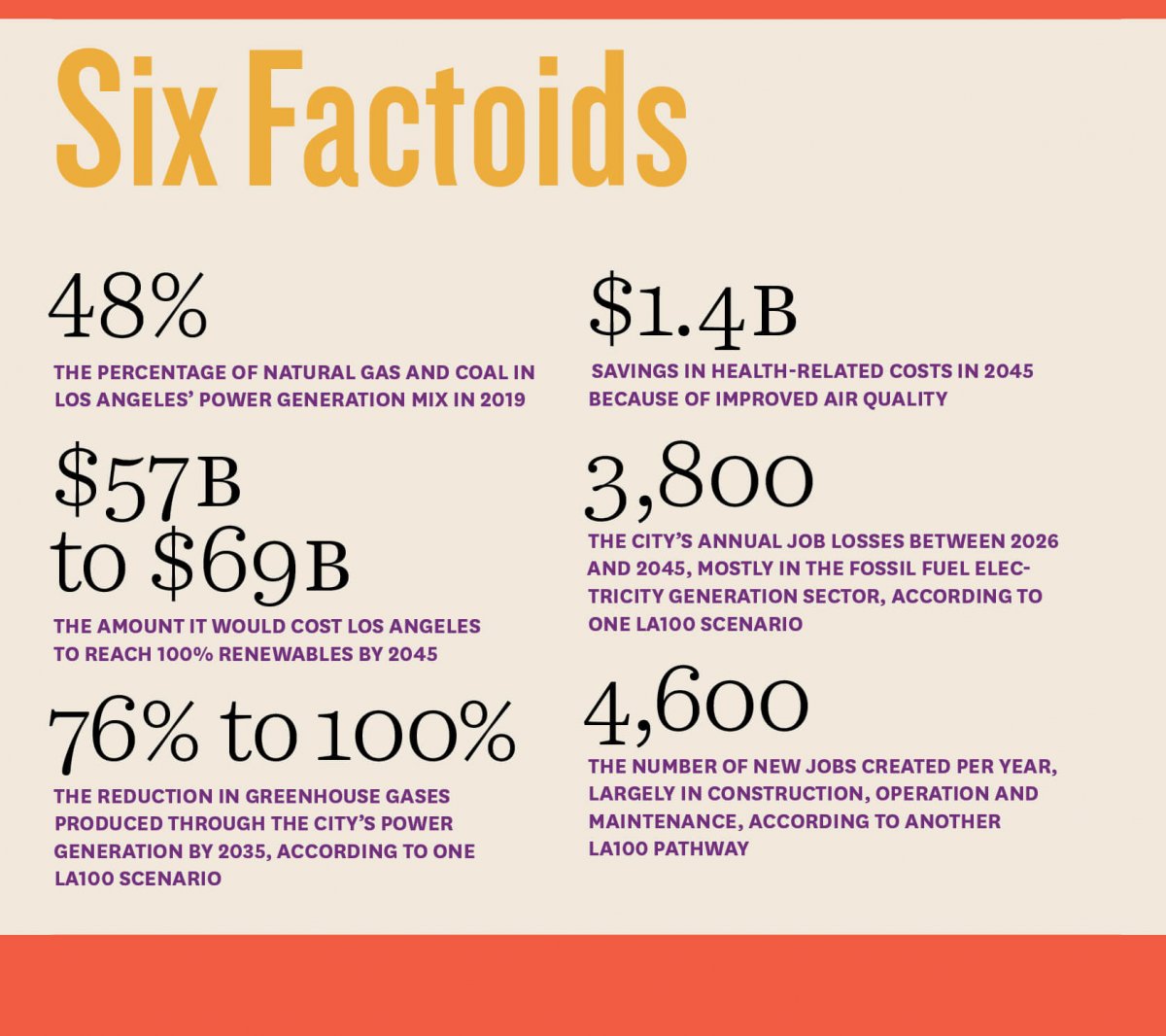

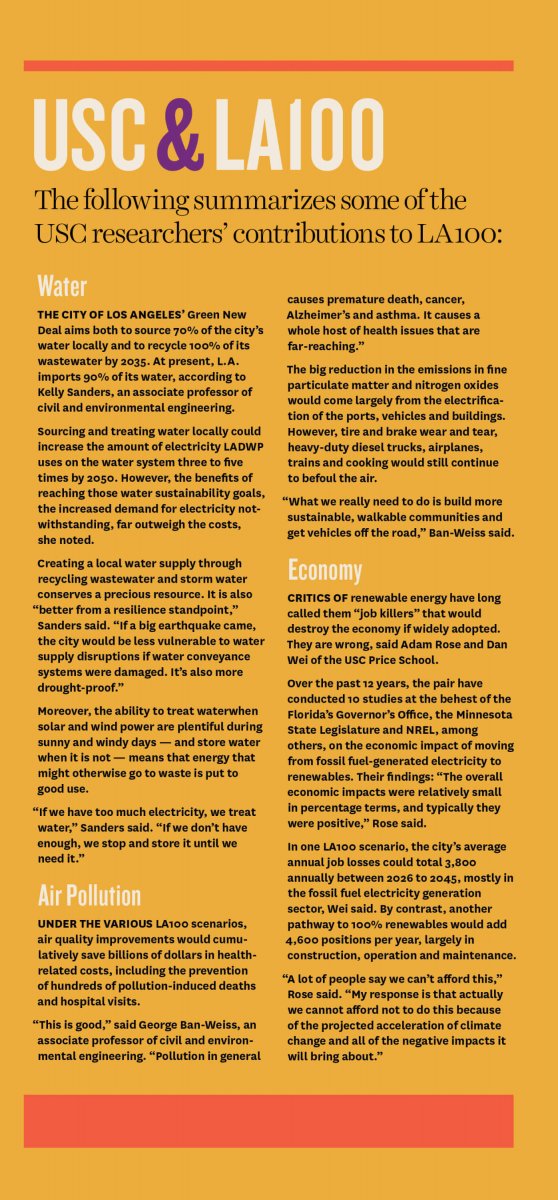

To help combat climate change and improve the air quality of the nation’s second-largest city, Los Angeles and the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Lab, or NREL, partnered to produce a path to a zero-emissions future. USC Viterbi and Sol Price School of Public Policy researchers, including Sanders, wrote portions of the report.

The LA100: The Los Angeles 100% Renewable Study, released in March, concludes that the city could be powered completely and reliably by 100% renewable energy by 2045, and perhaps even a decade earlier through an ambitious adoption of solar and wind power, hydropower and improved electrical storage, among other steps. The plan also envisions a surge in the popularity of electric vehicles, the electrification of buildings citywide, and people using energy when it is most plentiful during sunnier and windier hours.

In April, Mayor Eric Garcetti committed to transitioning Los Angeles to a carbon-free power grid by 2035, although it would still include some non-renewables such as nuclear energy, according to Lauren Faber O’Connor, L.A.’s chief sustainability officer. She added that renewables could account for 80% of the grid by 2030.

“The LA100 study shows us that a zero-carbon grid, a renewable energy grid, is achievable, reliable and affordable,” O’Connor said.

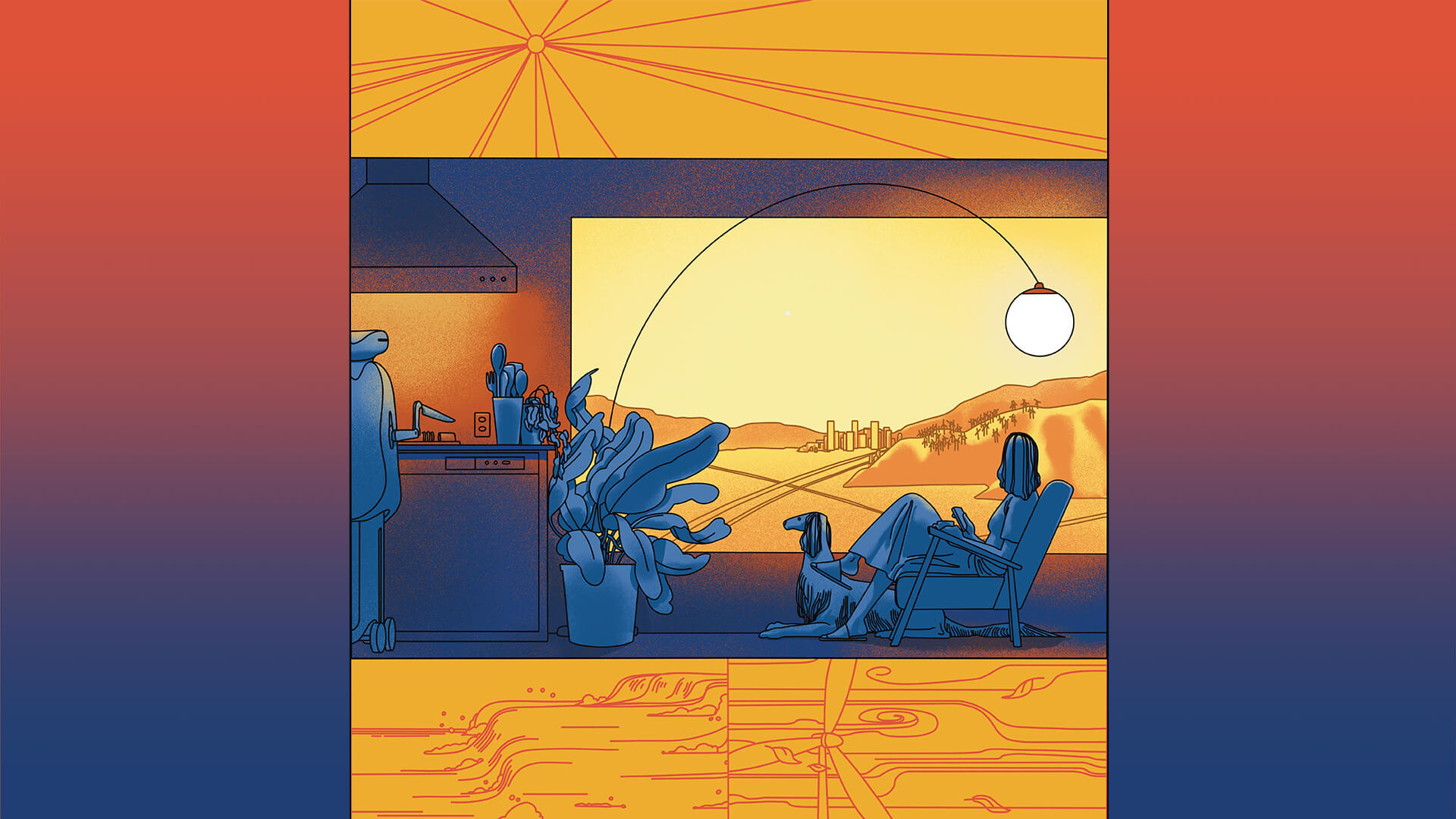

At present, natural gas and coal generate about 48% of the city’s electricity, according to NREL. To move to 100% renewables in the next 24 years or less “is a huge deal,” said Sanders, the Dr. Teh Fu Yen Early Career Chair and associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, and the author of the LA100’s chapter on water.

“Although some regions might power their grids with high fractions of renewables for short periods of time, there really aren’t many that are meeting the majority of their electricity demands with renewables all the time,” Sanders said.

“L.A. has already taken the lead by doing the study and committing to achieving a clean energy future. I think this could serve as an inspiration to others,” added Paul Denholm, NREL senior energy analyst and chief engineer for LA100 project.

How to get there

How to get there

The most comprehensive study of its kind, LA100 offers several different pathways for reaching 100% renewables. To answer questions about each scenario, including the potential environmental and health benefits and economic impacts, NREL and its partners modeled different projections for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) customer electricity demand, local solar adoption, power system generation, and transmission and distribution networks, among other data.

Additionally, researchers ran millions of simulations of thousands of local buildings to understand how new design elements, equipment or appliances would impact when and how much electricity people use. NREL used sophisticated aerial scans, including LIDAR, and customer adoption models for every rooftop in L.A. to ascertain how much rooftop solar could be installed. The projection: between 22% and 38% of existing single-family homes could go solar by 2045.

In the end, LA100 researchers concluded that the city could indeed reach its 100% renewable goal with limited pain and lots of benefits. That’s because solar and wind power, along with lithium ion batteries, have plummeted in price and increased in reliability, a trend that should continue well into the future, Denholm said.

To reach 100% renewables by 2045 would cost an estimated $57 billion to $69 billion. Doing so a decade earlier would cost about $86 billion. “A faster transition to 100% would likely require deployment of technologies at a higher cost, reflecting both technology maturity and commercial availability,” according to the report.

However, moving from 90% renewables to 100% remains a big challenge. To meet peak demand just a few times a year, the city must rely on expensive hydrogen-based technologies that are still under development. “We are not there yet,” Denholm said.

LA100 benefits

If enacted, LA100 promises a myriad of benefits, ranging from decreasing greenhouse gases that cause climate change to improving the city’s air quality, including in low-income areas with gas-fueled power plants.

“By moving to a zero-carbon clean grid, we will save 150 lives a year from better air quality, and support [thousands] of jobs annually in new investments in the clean energy sector,” O’Connor said. “This study shows that by making this transition we can have a tangible, positive impact on our residents.”

Under one particularly aggressive LA100 scenario, greenhouse gases produced through power generation could be reduced by 76% to 100% by 2035 compared to today’s levels.

Similarly, L.A.’s infamous brown, dirty air could become cleaner, clearer and healthier in the next 25 years, noted George Ban-Weiss, who penned the LA100 chapter on air pollution. Ban-Weiss, the David M. Wilson Early Career Chair and associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at USC Viterbi, said the emissions of fine particulate matter could fall up to 11% by 2045 when compared to 2012. Nitrogen oxides could drop as much as 59% during the same period. Overall, L.A.’s better air could save $1.4 billion in health-related costs in 2045 alone, according to the LA100 report.

“This is certainly moving us in the right direction,” Ban-Weiss said. He added that such dramatic pollutant reductions presuppose the widespread use of electric vehicles, the electrification of the Port of Los Angeles and neighboring Port of Long Beach as well as buildings, and the transition of fossil fuel-burning power plants to renewables.

In several LA100 scenarios, Valley Generating Station, located in the low-income, mostly Latino neighborhood of Sun Valley, would transition to clean energy, such as green hydrogen, or shut down and be replaced by a renewable energy facility. For three years, the natural gas-fired power plant leaked methane, which can cause respiratory problems and even convulsions in high enough concentrations, the Los Angeles Times reported. The city would also transition to cleaner renewables or replace its local gas power plants, including Harbor in the Wilmington neighborhood, Scattergood near El Segundo and Haynes in Long Beach.

Equally important, supporters of the city’s renewable future argue that the mix of hydropower, solar, wind and other clean energy sources, combined with new technologies, could keep Los Angeles’ power on every minute of every day of the year, even during the hottest summer days and coldest winter nights when demand peaks.

“You can have a reliable system with renewables,” Denholm said.

The good news: The transition to 100% renewable energy can happen with only minimal impacts on the local economy and jobs, said Adam Rose, a research professor at the USC Price School who co-authored the LA100 chapter about the economy with Dan Wei, a USC Price research associate professor.

“The shift to an all renewable electricity generating capability stimulates both an expansion and contraction of the economy, and they offset each other somewhat,” Wei noted. “ The L.A. economy is so large, however, that none of the impacts of the LA100 scenarios exceed more than seven-tenths of one percent of the L.A. economic output or employment base.”

Kelly Sanders Redux

The year is 2021, and Kelly Sanders is feeling contemplative.

Her mind flashes to March 2020, when the city shut down for several months with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. With few cars and trucks on the road, Los Angeles’ omnipresent smog lifted, revealing majestic mountain ranges and ocean views. Less than a year later, the dirty brown air returned when the economy reopened.

But not for long, Sanders believes.

With Los Angeles committed to the LA100 goal of powering the city with 100% clean energy, along with the expected widespread adoption of electric vehicles, buildings and ports, Sanders envisions a much cleaner and less congested city in the next 15 to 25 years — a far cry from the “Blade Runner” dystopia that many once imagined.

“Los Angeles is a city that has it all — beautiful snow-capped mountains, gorgeous beaches and interesting architecture. However, it has also been covered in a thick blanket of pollution for decades,” Sanders said. “I think people are really going to be amazed in how this transition toward a clean energy future improves our quality of life.”