More Than Words

Thousands of languages are teetering on the edge of extinction. In fact, of the estimated 7,000 languages spoken in the world today, nearly half are likely to vanish in this century, according to UNESCO. For Lina Brixey, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, it’s personal.

A linguistics graduate and polyglot who speaks French, Spanish and Portuguese, Brixey didn’t start learning Choctaw until she moved to Los Angeles in 2016 to pursue her Ph.D. in computer science at USC Viterbi. “I always came back to one question,” Brixey said. “Why don’t I speak my own language?”

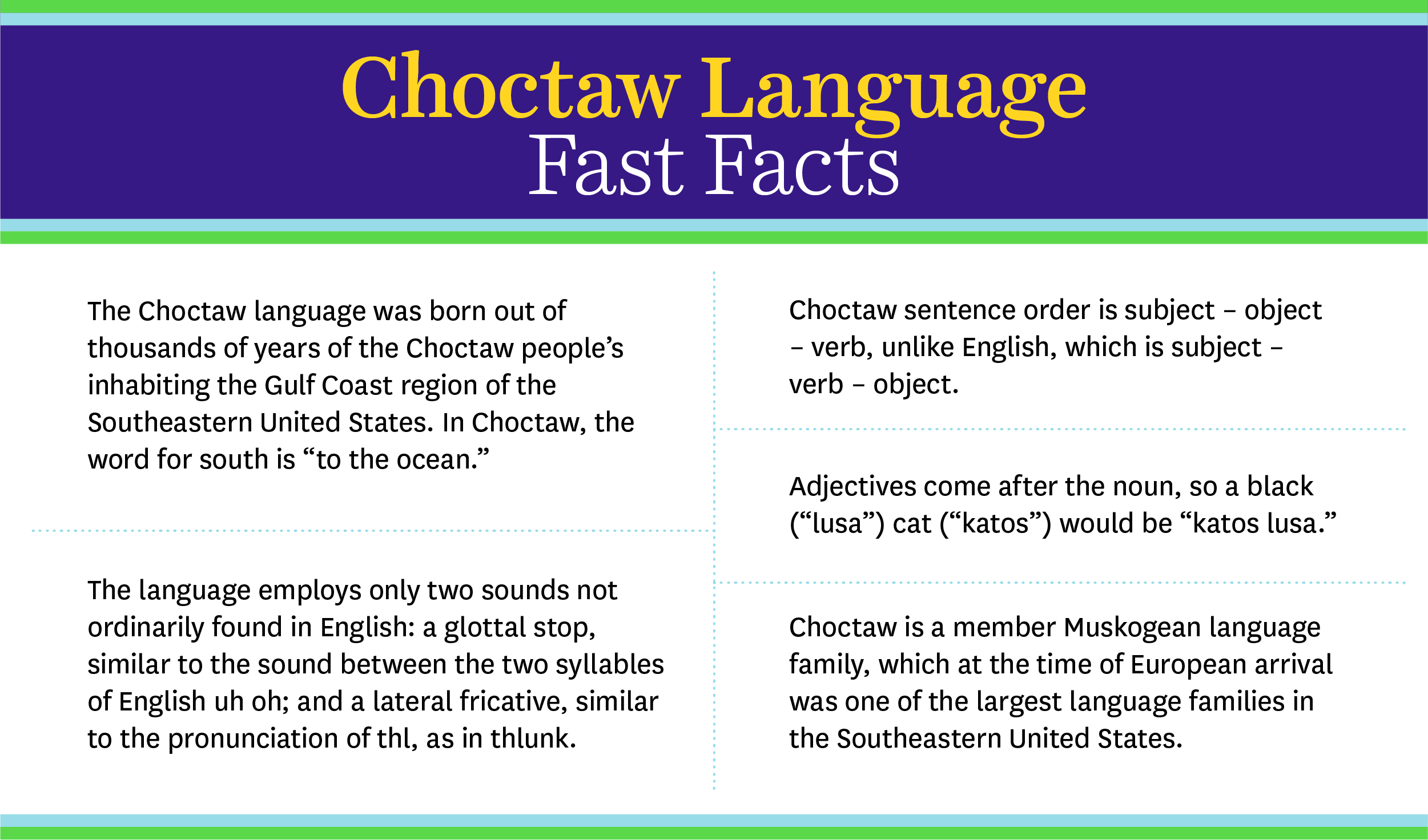

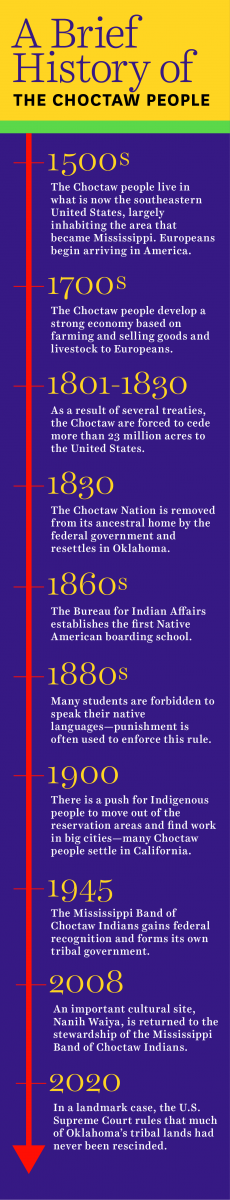

She’s not alone. Like hundreds of Indigenous languages of America, Choctaw is endangered, meaning that without intervention, it is likely to become extinct in the near future. Despite being the third-largest tribe in the U.S., recent estimates suggest only 7,000 Choctaw speakers remain. Crucially, as Brixey discovered, when a language dies, we lose more than just words: We lose cultures, traditions and unique world perspectives.

“Growing up, I had my tribal enrollment card, which is some kind of pedigree, but I never truly felt Choctaw until I could speak the language to a degree,” said Brixey. “When I started learning the language and meeting other Choctaw people, I realized the urgency of the situation.”

So she decided to do something about it. At USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), Brixey created the world’s first Choctaw language corpus — a collection of written and spoken texts essential for the study of languages — a bilingual chatbot and a dialogue system for language documentation.

Survival mentality

Brixey is Choctaw on her father’s side. (Her mother is of Irish descent.) Her great-grandfather, Noah Frazier, a minister and farmer in Oklahoma, was the last person in her family to speak Choctaw fluently.

“Starting in the 1800s, there was social pressure in schools for Choctaw and Indigenous people not to speak their languages,” Brixey said. “I think there was also a survival mentality — maybe my great-grandparents thought it was more important for my grandmother to learn English so she would have access to more opportunities.”

Nevertheless, Brixey was curious about her ancestral language. When she was 12 years old, her sister got a special gift from her grandmother: a Choctaw dictionary. Lina and her sister practiced secret conversations in Choctaw, but with no fluent speakers to learn from, their enthusiasm eventually waned.

“That’s something that is missing for a lot of us learning Choctaw and other Indigenous languages: We just don’t have access to fluent speakers,” Brixey said.

Living avatars

In the decades that followed, Brixey earned an undergraduate degree in journalism; studied abroad in Argentina, Brazil and Belgium; taught English in Spain and France; and received master’s degrees in both linguistics and computer science from the University of Texas, El Paso.

She found her niche in natural language processing, a subfield of artificial intelligence that focuses on enabling computers to process and understand human language. After coming to USC, Brixey put her linguistics and computer science skills to work developing a Choctaw language corpus. Named Choco, it now includes more than 300,000 Choctaw words and phrases painstakingly collected by Brixey from written and spoken archival materials.

At the same time, Brixey worked on the USC Shoah Foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony, which allows visitors to have one-on-one conversations with “living avatars” of Holocaust survivors. She tinkered around on the system’s back end, developed at ICT, and found it works much like a chatbot: When asked a question, the system trawls through a database of potential responses to select the most appropriate answer, simulating a real conversation.

This gave Brixey an idea: If people didn’t have access to fluent Choctaw speakers, could she simply invent one?

Fair skies ahead

It turned out, she could. Using the same back-end system, Brixey developed a chatbot called Masheli, Choctaw for “fair sky.” Working under the supervision of USC Viterbi Professor David Traum, Brixey selected 17 stories to form the chatbot’s responses. The conversational chatbot can “speak” in English or Choctaw and read stories in both languages. Brixey hopes it will serve as a resource for schoolchildren and adults with an interest in learning Choctaw.

But practicing the language is only one part of the preservation equation; the other half is documentation. So Brixey created a dialogue system that encourages speakers of endangered languages to converse and tell stories, creating audio recordings to support language research and revitalization. In 2019, she presented the system at the United Nations General Assembly for the International Year of Indigenous Languages.

Brixey is currently working on an automatic speech recognition system, much like the system used for Holocaust survivors. She is also archiving her corpus in Oklahoma-based museums for use by other researchers and language learners. Beyond this?

“The sky’s the limit,” she said. “Since this is the first and only corpus for Choctaw, I am excited to have laid the foundation to help other Choctaw researchers. I do hope one day we can have a living avatar system for Indigenous people to preserve our languages and stories. There are technical challenges to overcome, of course, but that’s the goal.”

Seven generations

It’s an Indigenous perspective to talk about seven generations: What can I do today that will positively impact people seven generations from now? “I guess that’s something I’ve embodied,” Brixey said.

She and members of the Los Angeles Choctaw Language Community Class have translated five children’s books together. Her dream? To see movies translated into Choctaw, and even Choctaw podcasts. Brixey, with countless other speakers of threatened languages, is not ready to let her ancestral language pass into history, even if the road to revival is a bumpy one.

“It feels like a dismissal when someone says it’s not worth my effort to work on those languages,” Brixey said. “Yes, our languages are endangered. But the fact is, our languages are not dead yet — they are very much alive. There is hope. If conservation efforts can bring wolves back from endangerment, I think it’s also true for languages.”