The Great ‘What-Ifs’ of USC Engineering

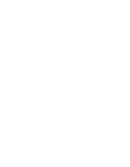

1) What if Zohrab Kaprielian had been left behind as a baby?

1) What if Zohrab Kaprielian had been left behind as a baby?

One of the most transformational deans in USC Viterbi’s history, Zohrab A. Kaprielian — who also served as USC’s provost and executive vice president during the 1970s — galvanized the school into a major research institution.

After convincing the U.S. Department of Defense in 1962 to award USC one of the coveted Joint Services Electronics Programs, Kaprielian assembled the school’s renowned “Magnificent Seven” communications faculty: Solomon Golomb, Bob Scholtz, Irving Reed, Charles Weber, William Lindsey, Lloyd Welch and Bob Gagliardi. Kaprielian also supported visionary projects like the Distance Education Network (DEN@Viterbi) and the USC Information Sciences Institute.

But it almost never happened.

Born in 1923, Kaprielian, the son of Armenian refugees, was left behind in his crib when his childhood home was attacked by marauders. His family fled in panic, only to remember the missing baby several hours later. When his parents returned to the Turkish city of Aintab (present-day Gaziantep), they discovered the infant Zohrab still in his crib, “surrounded by a hail of bullets,” according to Archbishop Vache Hovsepian in his 1982 memorial remarks for Kaprielian. Resettling in Syria, young Kaprielian attended primary school in rags. Despite this, he was always first in his class — though his primary school trustees nearly refused to let such a destitute student deliver the valedictory speech.

He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in applied physics in 1942 and 1943 from the American University of Beirut. According to his niece, Arpine Deraney, Kaprielian may have been aided by AUB or UC Berkeley in coming to the United States after World War II, where, at Berkeley, he received his Ph.D. in electrical engineering in 1954. He came to USC in 1957, and the rest is Trojan history.

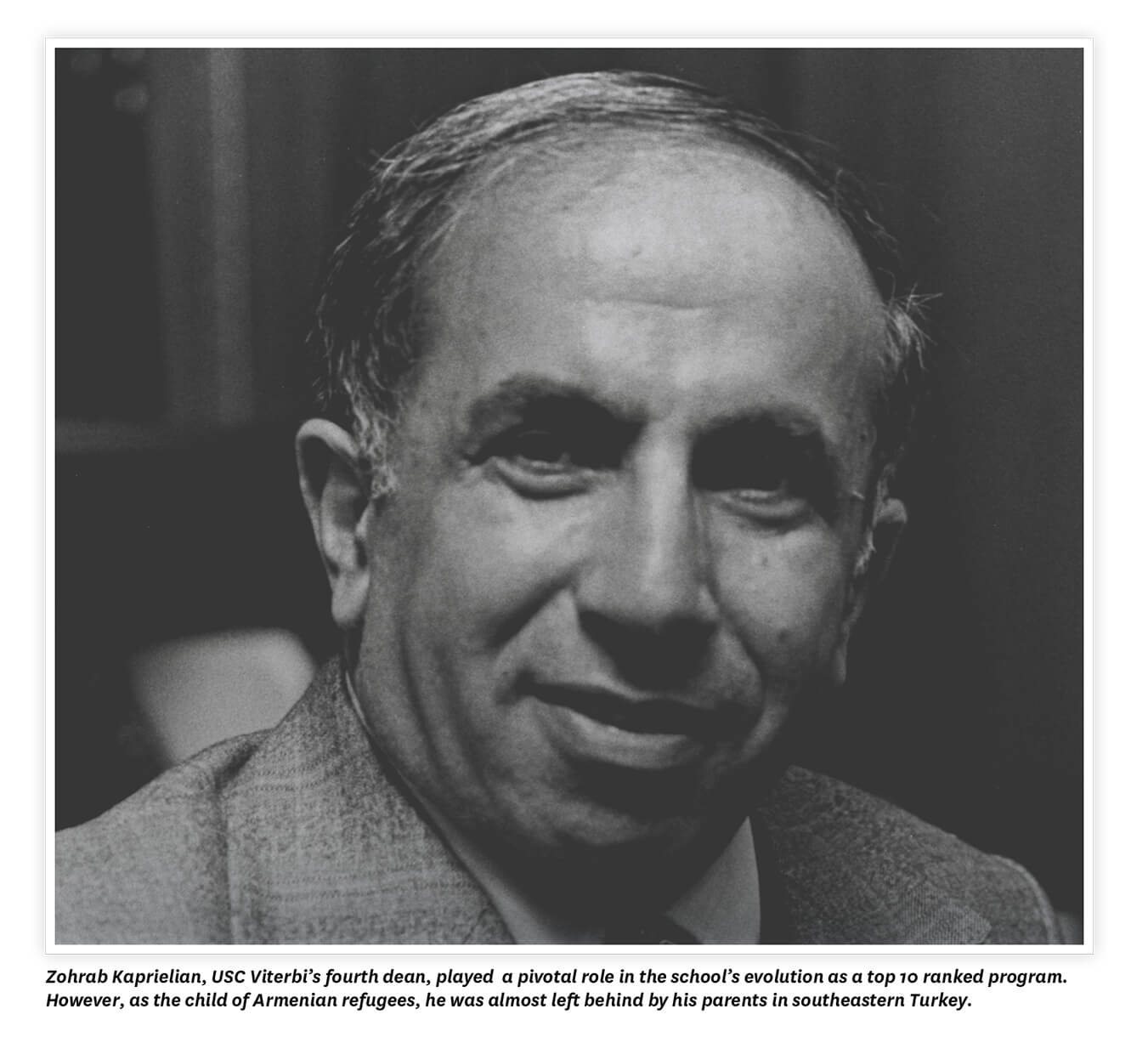

2) What if Judith Love Cohen hadn’t worked for the space program?

2) What if Judith Love Cohen hadn’t worked for the space program?

Judith Love Cohen, B.S. ’57, M.S. ’62, was a celebrated author of children’s books like “You Can Be a Woman Engineer.” She was the mother of Neil Siegel, a member of the National Academy of Engineering and a USC Viterbi faculty member, as well as the actor and musician, Jack Black. But perhaps her proudest achievement, according to Cohen’s son, Neil, was working on the Apollo space program.

As an engineer for TRW (Thompson Ramo Wooldridge Inc.), a subcontractor on the Apollo missions, Cohen was a member of the team that created the abort guidance system, or AGS, an early digital computer that had a very important job. Much of the maneuvering and flight of the Apollo spacecraft was planned and computed well in advance. But in the event of an aborted moon landing, the AGS could provide the necessary calculations to allow the lunar lander, with its two astronauts on board, to safely return to the command module, where a third astronaut awaited in lunar orbit.

During the Apollo 13 mission in 1970, the oxygen tank exploded, destroying the ship’s engine, life support and power systems, and forcing the three astronauts, Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise, to use the lunar lander as a “lifeboat.” With no power for the command module’s primary navigation computer, the crew relied entirely on the lander’s AGS to plot 238,000-mile trip back to Earth, including two course corrections. In addition, Cohen was part of TRW’s “orbitology” team that designed the trajectory paths to get the astronauts from the Earth to the Moon and back. Without this, the AGS would have been useless.

Cohen’s son, Neil Siegel, recalled: “After they returned to Earth, the Apollo 13 astronauts came to TRW in Redondo Beach to thank the three TRW teams — orbitology, LEM descent engine and LEM abort guidance system — that also helped get them home. I was just a teenager, but my mom took me to that event.”

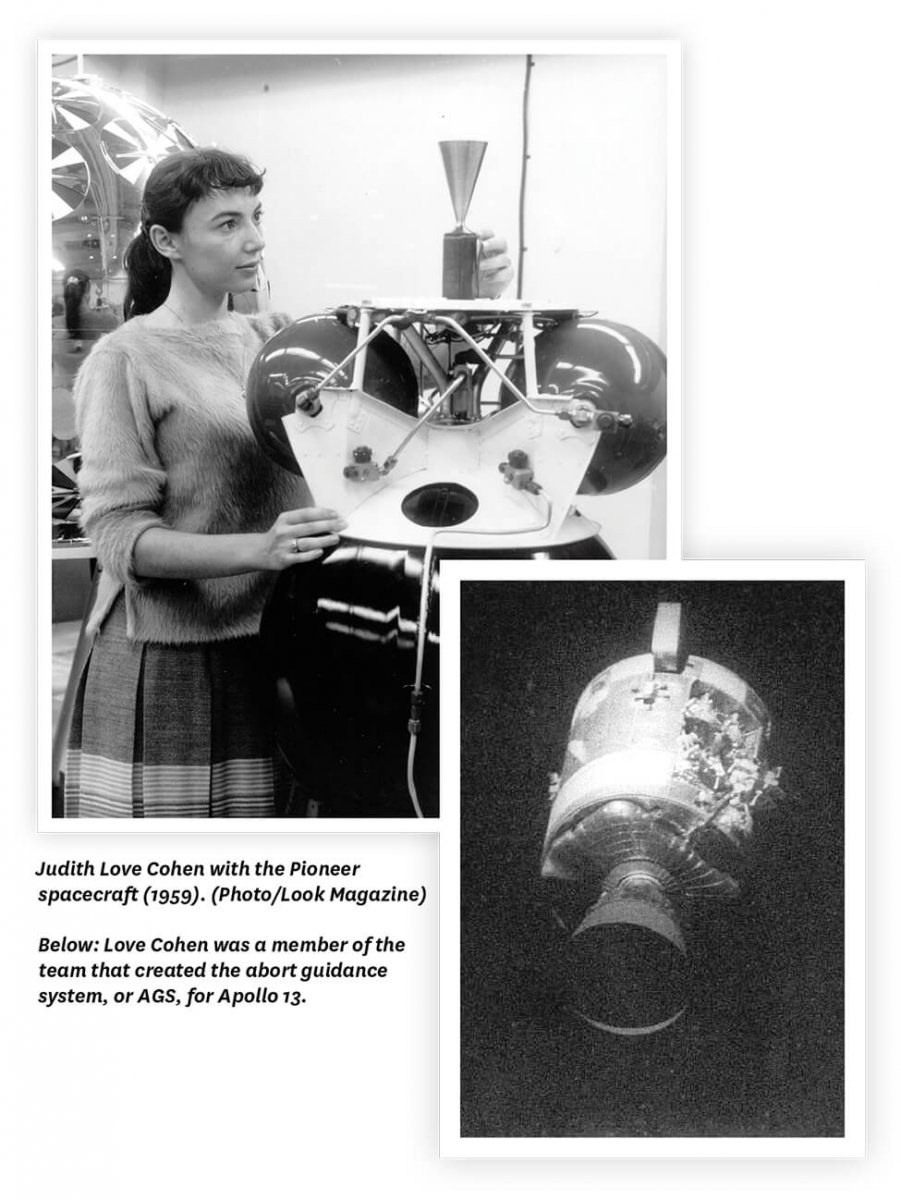

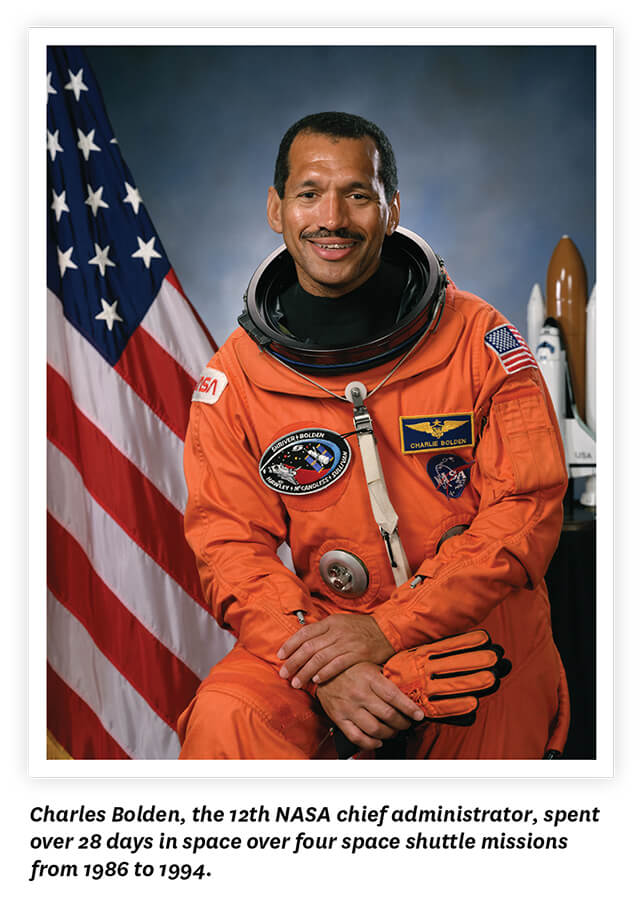

3) What if Charlie Bolden hadn’t watched “Men of Annapolis”?

3) What if Charlie Bolden hadn’t watched “Men of Annapolis”?

Growing up in segregated South Carolina, 12-year-old Charles Bolden fell in love with the sharp suits and tradition of the U.S. Naval Academy through the 1957 television series “Men of Annapolis.” Every episode opened with the words: “These are their stories, full of their laughter, their heartache, their tragedies and triumphs … the stories of the Men of Annapolis!”

Inspired, Bolden wrote to both his senators and to Lyndon Johnson, then vice president of the United States, seeking a necessary appointment in the academy. Said Bolden, “I wanted them to know, early on, who I was and that I was really serious about this.” Unfortunately, the responses from his congressmen, which included the segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond, made it clear they were “not going to appoint a Black to the academy,” Bolden said. Still, he was hopeful that LBJ would appoint him. That is, until November 22, 1963, when he learned — on the way to Charleston to play for the state football championship — that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, and Johnson was now the president.

“My world stopped,” Bolden told the “Consider the Cosmos” podcast in 2020, “and it was selfish. Not only had we lost the president we all loved, but I had lost any hope of going to the Naval Academy. Johnson was going to become president, and I wasn’t eligible for a presidential appointment.”

Undeterred, Bolden wrote to the new president. Within weeks, a Navy recruiter was knocking on Bolden’s door, leading to an appointment from U.S. Rep. William L. Dawson from Chicago.

Undeterred, Bolden wrote to the new president. Within weeks, a Navy recruiter was knocking on Bolden’s door, leading to an appointment from U.S. Rep. William L. Dawson from Chicago.

After graduating from the Academy, Bolden became a Marine aviator and test pilot, eventually earning his master’s in systems management from USC in 1977. In 1980, Bolden got the call from NASA and replaced a crisp Marine Corps Nomex flight suit for a spacesuit, which he wore on four Space Shuttle missions from 1986 to 1994. In 2009, Bolden received one more presidential appointment: President Obama nominated him to become the 12th Administrator of NASA. With his Senate confirmation, he became the only African American to hold that post in the agency’s 63-year history.

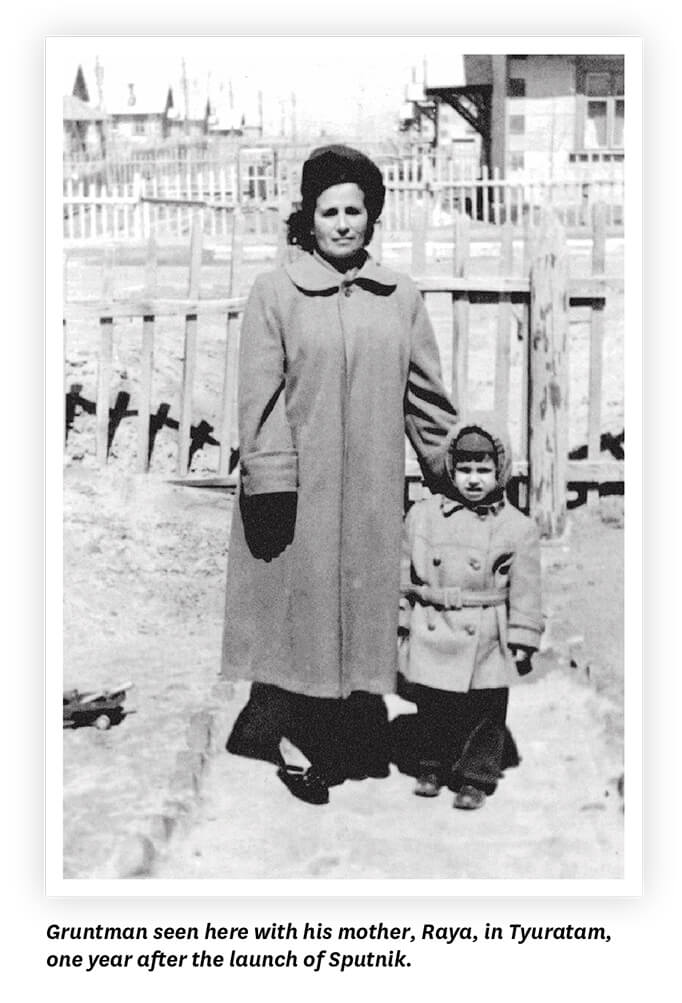

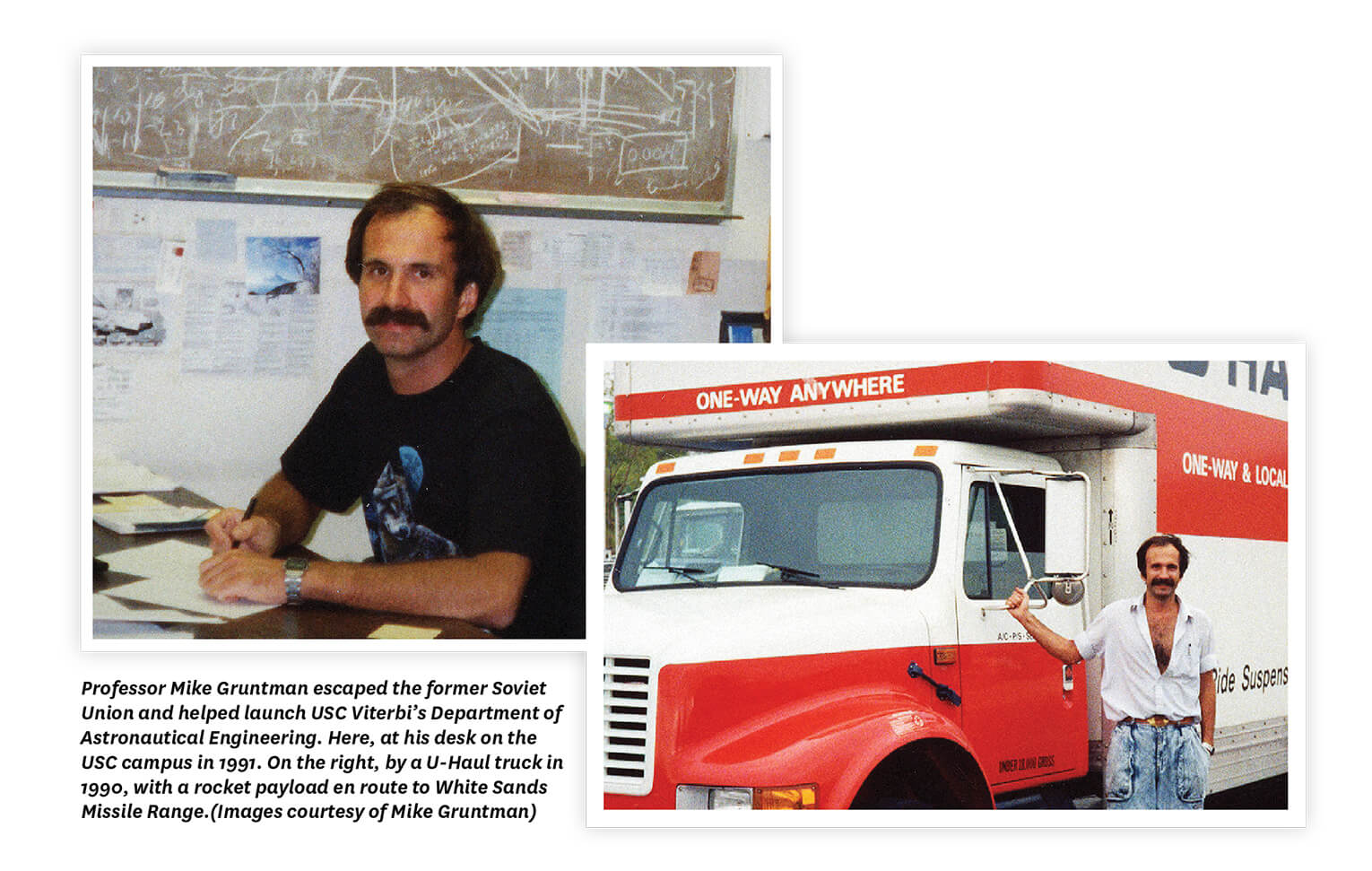

4) What if Mike Gruntman had not escaped the Soviet Union?

4) What if Mike Gruntman had not escaped the Soviet Union?

Mike Gruntman, USC Viterbi professor of astronautics and aerospace and mechanical engineering, has helped build one of the largest academic space engineering programs in the United States. It’s the lifeblood of private space companies like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic. It’s the home of the USC Rocket Propulsion Laboratory, which in 2019 launched the first student-built rocket to outer space. It’s the first and only university to offer a B.S., M.S. and Ph.D. in astronautical engineering.

It’s perhaps no exaggeration to say the department would not exist without Gruntman. But what if he had never escaped the Soviet Union?

In an alternate world, Gruntman should have been a favorite son of the Soviet space program. As a 3-year-old raised in Tyuratam — a secret location deep in present-day Kazakhstan — he was one of the world’s few witnesses to the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the first man-made satellite. His father was the chief engineer who built the cosmodrome, or Russian spaceport, from which Sputnik launched.

But though he earned his Ph.D. in physics from the Space Research Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences and worked as a researcher for the IKI and IPM institutes, Gruntman turned anti-communist at an early age. In 1984, he tasted tear gas for the first time, aiding the Polish Solidarity movement against riot police imposing martial law in Gdansk. When the “cracks developed in the Iron Curtain,” Gruntman found himself in a Dutch airport in March 1990. Three days later, with $80 in his pocket, Gruntman walked into a new office and new life at USC.

Though Gruntman is not ready to share the exact details of his complex escape plan, he relied heavily on the support of colleagues and friends from six countries on three continents. One of these was Darrell Judge ’63, Ph.D. ’65, professor emeritus of physics and astronomy and astronautical engineering at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. Judge, Gruntman recalled, helped him escape from the former Soviet Union and make the transition to the scientific community at USC.

“Darrell’s generosity, hospitality and friendship have touched the lives of many people, including mine,” Gruntman said. “As I started my life from scratch in the U.S., he warmly welcomed me to his group at USC and offered the hospitality of his home during my first week in Los Angeles.”

“Darrell’s generosity, hospitality and friendship have touched the lives of many people, including mine,” Gruntman said. “As I started my life from scratch in the U.S., he warmly welcomed me to his group at USC and offered the hospitality of his home during my first week in Los Angeles.”

Gruntman would go on to map the interstellar frontier of our solar system in 2008 (a project he began at age 24!) as part of the IBEX spacecraft team. But none of it would’ve been possible without first reaching a new terrestrial frontier in Southern California.

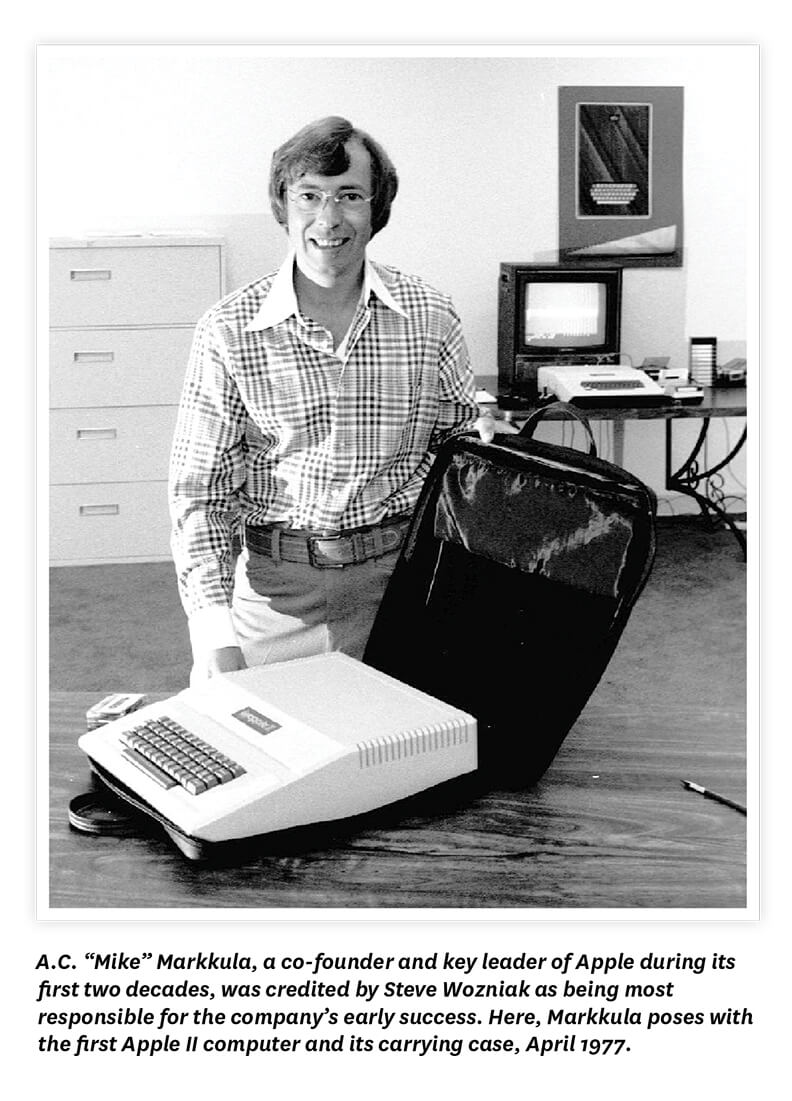

5) What if A.C. “Mike” Markkula did something else on Mondays?

“A lot of people wouldn’t invest in Apple, wouldn’t even talk to Apple, because Steve [Jobs] was so odd,” recalled venture capitalist Don Valentine, founder of Sequoia Capital.

Nolan Bushnell, founder of Atari (where Jobs worked) said no. Tom Perkins, co-founder of Kleiner Perkins, said he “very foolishly didn’t even look at Steve and [Apple co-founder Steve] Wozniak.” Although Valentine dismissed Jobs and Wozniak as “renegades from the human race,” he did refer them to an old colleague from his Fairchild days.

That colleague was A.C. “Mike” Markkula Jr., who was arguably the first to recognize the full potential of the Apple II.

Markkula, B.S. EE ’64; M.S. EE ’66, a millionaire from stock options as an Intel marketing manager, spent his days teaching himself to read music for guitar and building custom wood furniture for his A-frame cabin in Lake Tahoe.

“Every Monday, I’d help people write business plans and find financing to start companies. I thought it was fun. But I only did it Mondays,” Markkula said.

One Monday, he pulled into the driveway of Paul and Clara Jobs’ home in Los Altos.

Markkula entered the garage, looked past their unkempt 22-year-old son, Steve, and his buddy, Steve Wozniak, and pondered the machine on the workbench.

Markkula, the USC trained engineer, knew it was “a massive achievement.” He came out of retirement and wrote Apple’s original business and marketing plans. He made the original $250,000 investment that launched Apple and leveraged his professional experiences and relationships to help build Apple into a Fortune 500 company in less than five years. For over 20 years, Markkula led Apple in various capacities, from CEO to chairman of the board, leading to Jobs’ ultimate return in 1997.

“Steve and I get a lot of credit, but Mike Markkula was probably more responsible for our early success, and you never hear about him,” Steve Wozniak told Failure Magazine in July 2000.

Today, with a market capitalization of $2.1 trillion, Apple is the biggest company in the world. But it might never have existed as the behemoth we know today without Markkula, its lesser-known co-founder.

6) What if UCLA had moved faster the day Keith Uncapher had called?

6) What if UCLA had moved faster the day Keith Uncapher had called?

In 1972, technology maverick Keith Uncapher received an unusual offer. His work at Santa Monica, California-based think tank RAND Corp., where Uncapher directed the computer science division, had drawn the attention of the United States’ Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Create and lead a center for emerging technologies, said DARPA officials, and the agency would provide financial support.

Uncapher initially approached the University of California at Los Angeles, where he was told it would take 15 months to receive approval from the UC Board of Regents. But given DARPA’s interest, Uncapher felt he had no time to waste.

He appealed to George Bekey, chair of electrical engineering systems at USC and a consultant to RAND. Bekey helped arrange for Uncapher to meet with USC’s dean of engineering, Zohrab A. Kaprielian, who wielded considerable influence — and who thought Uncapher’s concept had tremendous promise.

USC’s Board of Trustees authorized the center just five days later. In less than a month, the Information Sciences Institute, or ISI, launched operations as a largely autonomous arm of USC’s School of Engineering. At Uncapher’s insistence, the new center was located off campus to maximize its entrepreneurial bent.

From its 12-story, oceanfront building in Marina Del Rey, ISI conceived wonders. In 1972, ISI designed an interface for ARPANET, which later becomes the basis of the internet. In 1981, Danny Cohen created MOSIS, probably the world’s first e-commerce site. Two years later, Paul Mockapetris created the internet’s Domain Name System (DNS), enshrining .com, .gov and .edu, among others. In 2011, ISI established the USC-Lockheed Martin Quantum Computation Center, the first academic research center in quantum computing. In 2016, Pegasus software, whose development is led by Ewa Deelman, was instrumental in detecting gravitational waves, contributing to a recent Nobel Prize.

Today, ISI is USC’s crown jewel research institute. But nearly 50 years ago, it might have been UCLA’s.