Centuries ago, when humankind decided to take to the sky, engineers like Otto Lilienthal, the so-called “flying man,” began by modeling their craft after the most well-known masters of flight — birds.

However, after successes like the Wright Brothers’ Flyer in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, progress diverged from following examples of natural flight. In 1936, the Douglas DC-3 already had the defining elements of what has been called the tube and wing configuration, where a pair of main wings supports the tubular fuselage that extends to carry a stabilizing tail-plane. Now, researchers like USC Viterbi’s Geoff Spedding are once again looking to birds for inspiration for future aircraft.

“There are independent reasons for thinking that bird shapes may be efficient, which reopens questions about what an engineered equivalent might look like. If we make a bird, or bird-like plane, then what type of bird would it be? The answer depends on the mission and on the sophistication of our materials and aerodynamic controls,” said Spedding, a professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering who holds a Ph.D. in zoology.

From wing design to flight tactics, here is a collection of eight birds that Spedding says can teach us a thing or two about flight.

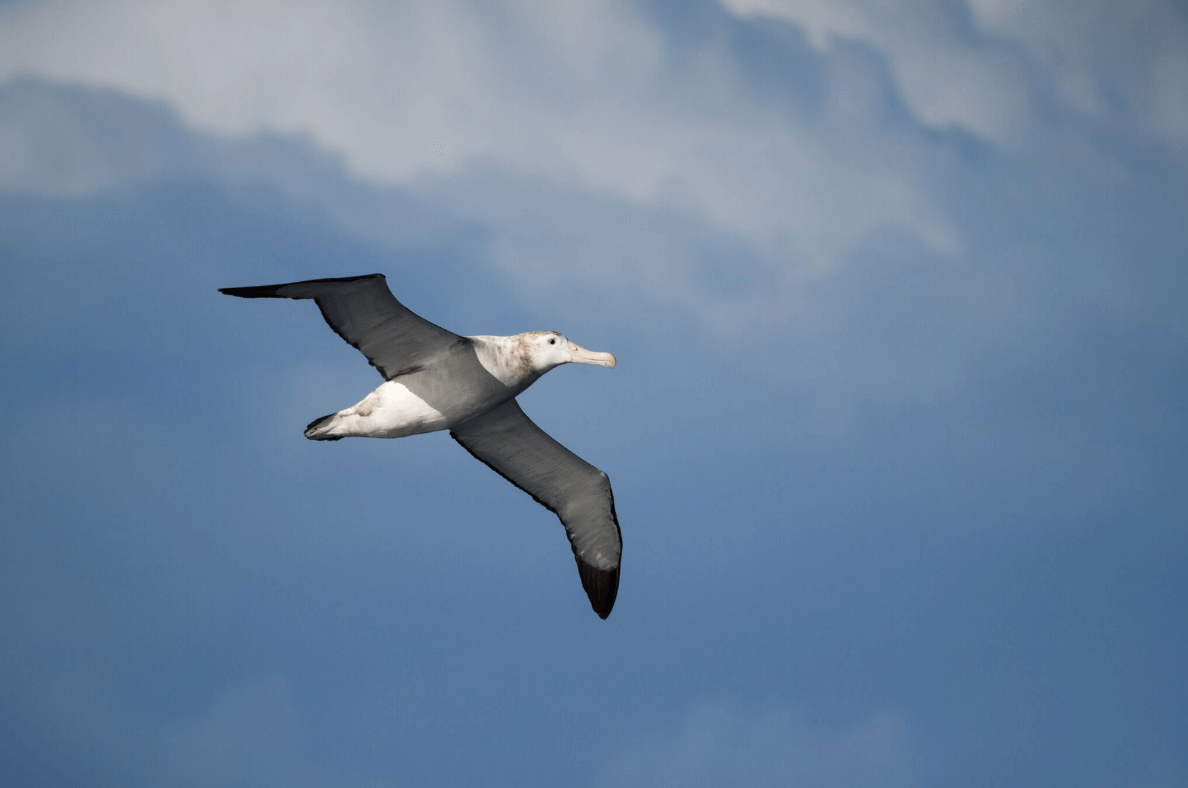

Wandering Albatross

(Diomedea exulans)

Weight: 14–26 pounds; average wingspan: 10 feet, 2 inches

Expert glider

A true glider, the wandering albatross rarely flaps its wings. It even has a special locking mechanism in its shoulder to hold them in place. It uses surrounding wind energy to stay aloft, even in complex, turbulent flows. No man-made aircraft does this.

Trumpeter Swan

(Cygnus buccinator)

Weight: 15–30 pounds; wingspan: 6 feet, 8 inches

Long-range flapping device

The trumpeter swan is the heaviest bird in North America, needing a 100-yard runway in order to take off. Its enormous wings are the perfect inspiration for sturdy, long-range flapping devices, known as ornithopters. It could be that a flapping wing device with a large payload ought to mimic some swan-like features.

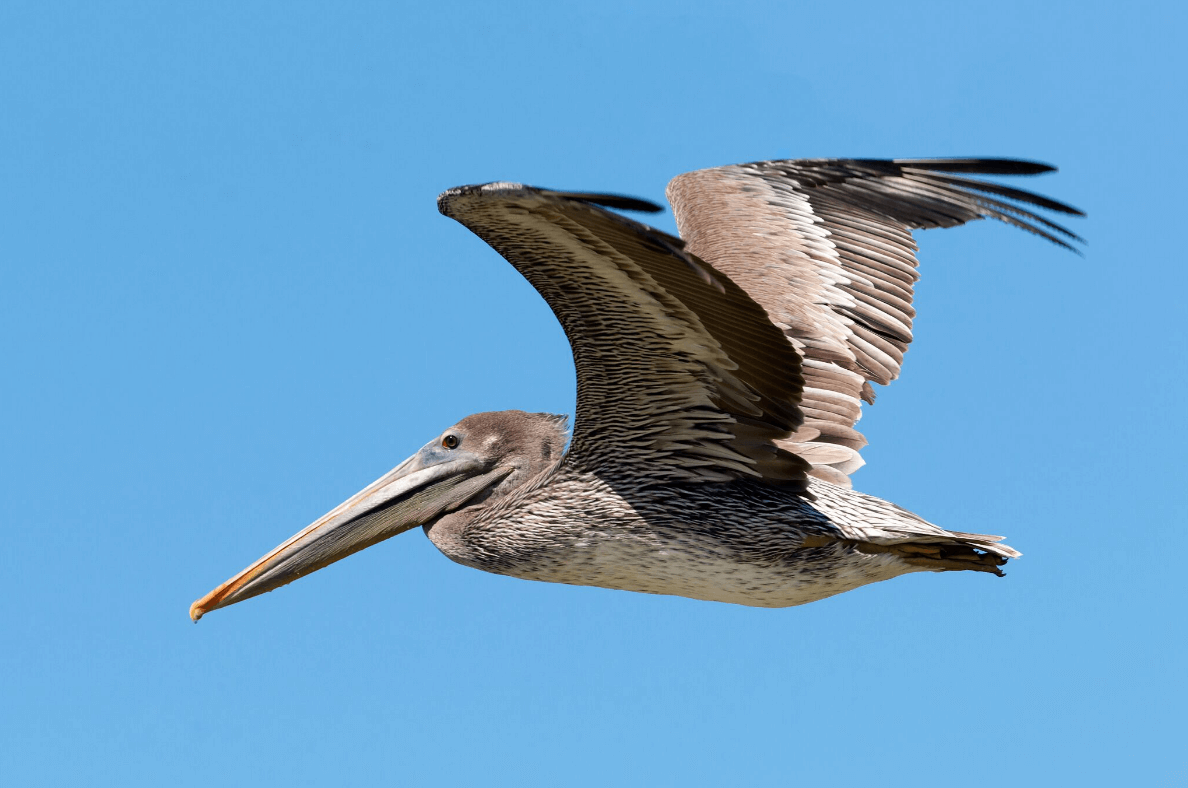

Brown Pelican

(Pelecanus occidentalis)

Weight: 4.4– 11 pounds; wingspan: 6 feet, 7 inches

Formation flight

Flocks of brown pelicans can be seen traveling along the western and southern coasts of the U.S., rising and falling in unison with the waves below. Flying so close to the water allows them to use what pilots call “ground effect,” improving the lifting efficiency of an aircraft. “An imagined brown pelican UAV [unmanned aerial vehicle] would be able to extract energy from the environment in several ways,” said Spedding, “from closely following each other with appropriate spacing and phase delay between wing beats; from maximizing ground effect even over uneven and moving terrain; by following updrafts on large surface waves; and by switching to alternate, known sources of free energy (such as slope-soaring) when conditions change.”

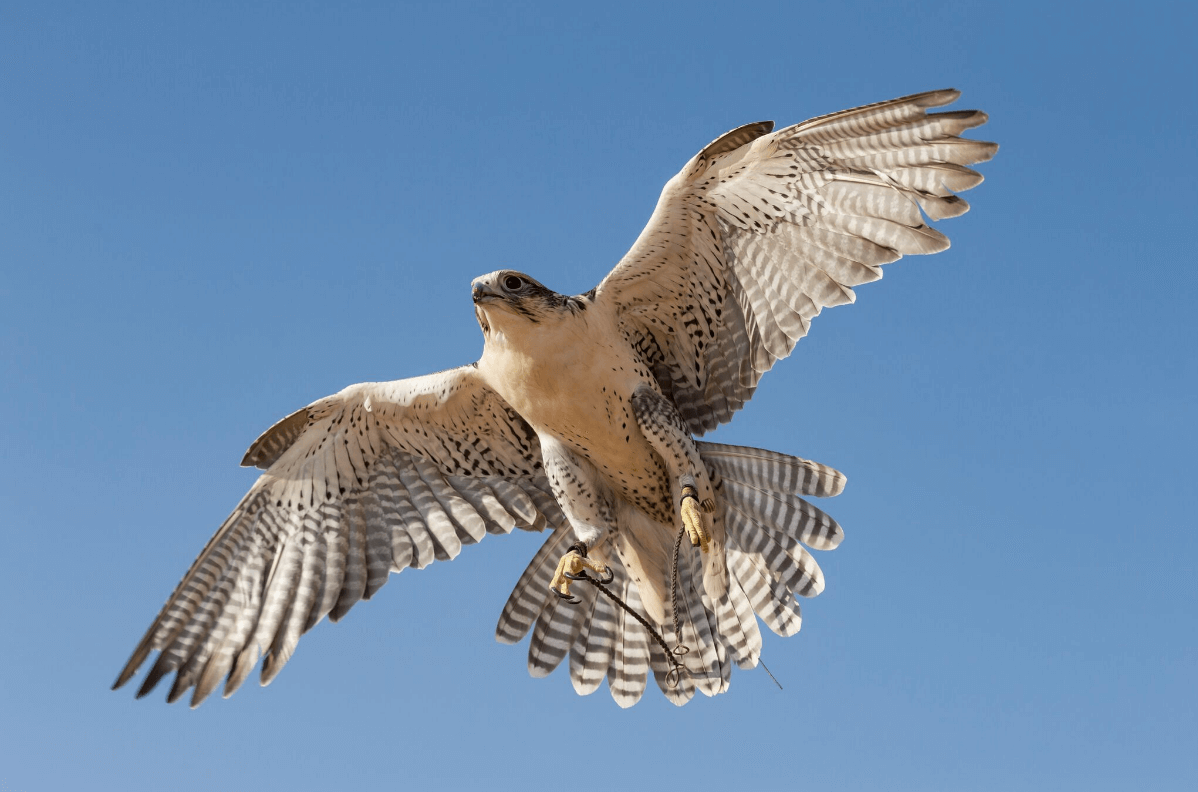

Peregrine Falcon

(Falco peregrinus)

Weight: 1.2–3.5 pounds; wingspan: 3 feet, 4 inches

Morphing wings

The fastest recorded bird, the peregrine falcon can reach speeds up to 200 miles per hour while diving to catch its prey. Able to tuck in its wings and create an aerodynamic shape, it is an “excellent example of morphing wings with large shape change according to flight mission segment,” said Spedding.

Great Cormorant

(Phalacrocorax carbo)

Weight: 5.7–8.2 pounds; wingspan: 4 feet, 7 inches

Air to water vehicle

In addition to flying in the air, the cormorant can fly through the water in pursuit of its prey. Their small wing design allows them to operate underwater, requiring them to beat notably faster to fly in the air. “There are advanced military and civilian search and rescue missions where the ability to operate in both air and water would be extremely helpful,” Spedding said.

Broad-tailed Hummingbird

(Selasphorus platycercus)

Weight: 0.1–0.2 ounces, wingspan: 5 inches Agility

These small wonders can fly backwards and upside down, as well as hover indefinitely while their wings beat 50 times per second. “Their agility would be extraordinary to mimic,” said Spedding. “The small size would also make them very hard to detect.”

Turkey Vulture

(Cathartes aura)

Weight: 1.8–5.3 pounds; wingspan: 5 feet, 9 inches

Endurance

Another famous glider, the turkey vulture can spend hours gracefully soaring riding columns of rising air, called thermals, just as competition glider planes do. By using the vulture’s technique for quick turns and thermal detection, Spedding said, “it would allow us to design a UAV with all-day endurance.”

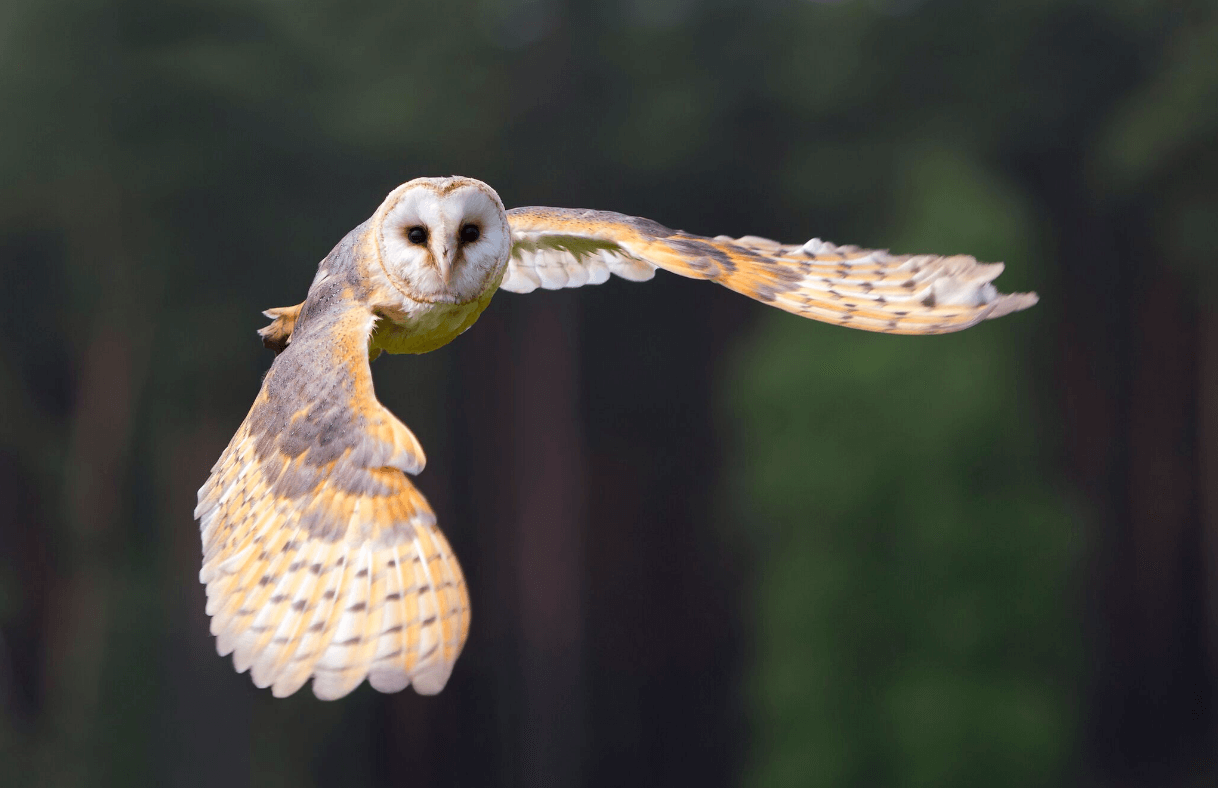

Barn Owl

(Tyto alba)

Weight: 0.9–1.5 pounds; wingspan: 3 feet, 9 inches

Stealth

The barn owl is able to fly in complete silence thanks to some unique features. Compared to their body mass, they have large wings that allow them to fly surprisingly slowly as they glide quietly though the air. In addition, the edges of their wing feathers are lined with comb-like serrations that break up turbulent air and act as a silencer during flight. Said Spedding, “The ability to fly without making noise would be a huge advantage in stealth applications in environments where we are trying to map or detect noise.”