People Before Profits

For much of the Min Family Engineering Social Entrepreneurship Challenge, participant Daniel Huertas was “very much in a business-oriented mental state,” he said.

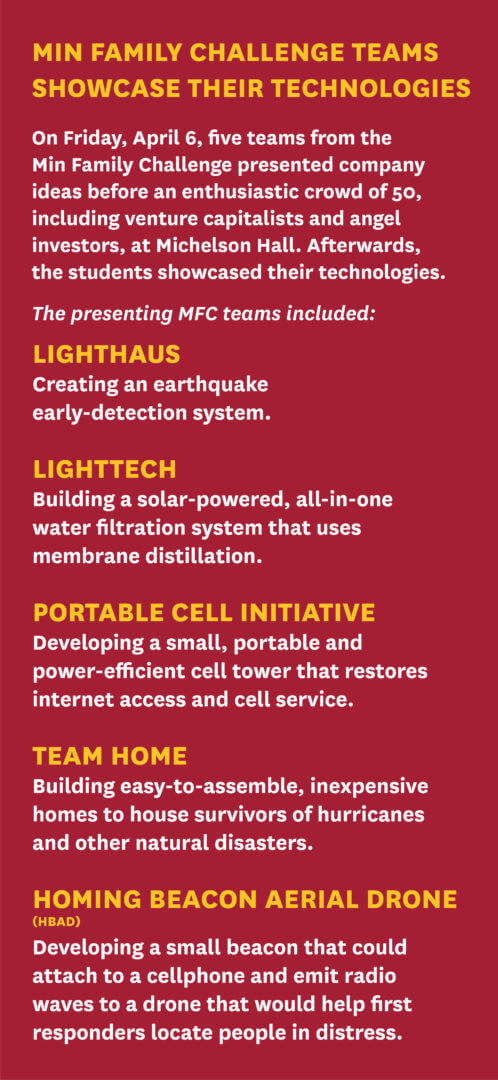

The Min Family Challenge (MFC) encourages would-be entrepreneurs like Huertas to build companies that benefit society. This year, the program focused on developing sustainable ventures to enhance relief and recovery efforts for the victims of natural disasters, and mitigate their impact in the future. USC Viterbi partnered with the USC Marshall Brittingham Social Enterprise Lab to prepare the students for effective problem discovery in a disaster zone.

“We could not ignore the great needs left in the wake of our deadliest and most catastrophic natural disaster season ever, with the likes of hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria, earthquakes in Mexico, fires in Santa Rosa [California], and other tragedies,” said Alice Liu, assistant director for USC Viterbi’s Office of Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship. “We needed to do something.”

Huertas’s perspective and priorities shifted dramatically after visiting with Hurricane Harvey survivors and others in Texas over Martin Luther King Jr. weekend in January. He and 16 other students and alumni witnessed the devastation wrought by the Category 4 storm, which killed 88 people and caused $125 billion in damage. In dozens of interviews with local residents and experts, they acquired on-the-ground knowledge about what actually transpires in a natural disaster and its aftermath.

“Before I came to Texas, I thought about building a product, making it great, making money and helping people,” said Huertas, a USC Viterbi graduate student in computer science. “For me now, it’s a little more personal after meeting survivors and first responders. I’m not as concerned about the monetary gains at the end. I’m more concerned that our device is deployable, affordable, and will save as many lives as possible.”

That device is Lighthaus — an early-warning system for earthquakes. The idea? Seconds could save your life. Huertas and his three-member MFC team developed a tiny, sensor-laden computer that plugs directly into a wall outlet that would alert users of an impending temblor, giving them valuable time to move away from a window, get off a ladder or safely exit a house or building.

Hurricane Horror

Before landing at Houston’s Hobby Airport on Jan. 12, many of the MFC participants assumed that the nation’s fourth-most populous city bore the brunt of Hurricane Harvey.

Indeed, about one-third of the city was underwater just 24 hours after the storm made landfall, forcing thousands out of their homes and into shelters. The “Houston Chronicle” reported that Harvey damaged more than 30 percent of the city’s housing, or 311,000 housing units.

The national media’s focus on Houston led government agencies and volunteers to react relatively quickly. That was not the case with many of Texas’s harder-hit rural small cities and towns. Hamshire, in the state’s Golden Triangle, experienced some of the worst destruction from Hurricane Harvey. Unfortunately, this region saw little media coverage of the storm’s effects.

Justin Chesson, chief of the Hamshire Volunteer Fire Department, told the visiting MFC participants that the torrential rains had isolated Hamshire from the world for several days. “We couldn’t get anybody in and we couldn’t get anybody out,” he said. “We couldn’t get no help. They kind of forgot about us.”

Giving Back

Geri Brown wasn’t so lucky. The 71-year-old great-grandmother lost her 2,500-square-foot house in Vidor when officials released water from two nearby swollen dams. Brown held on as long as she could, even trying to bail water out of her house. Cajun Navy volunteers evacuated her by boat.

Better Companies

Min Family Challenge participants experienced more than just personal transformations during their four days in Texas. They revised their company ideas after meeting with first responders, government officials and volunteers. The feedback they received led many of the aspiring entrepreneurs to improve their business models.

The Trip of a Lifetime

Susan Angus, executive director of the Commission on Voluntary Service & Action, was one of the early believers of the MFC mission. She helped bridge connections with local government officials, relief groups and other community members. Min Family Challenge participants met with members of the United Saints, the Cajun Navy, the Cajun Army and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, among others.

Helping Startups Get Started

The Min Family Challenge launched in October 2015 with a generous gift from alumnus Bryan Min, a member of the USC Viterbi Board of Councilors, and his family. MFC provides USC Viterbi students, alumni, and other aspiring entrepreneurs with the tools to use innovations in engineering and technology to develop sustainable and effective solutions to global problems.

“A heavy emphasis in our curriculum is on understanding the customer, or user, intimately,” said Alice Liu, assistant director for USC Viterbi’s Office of Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship. “That’s why this year the Min Family Challenge sent students to ground zero in Hamshire, Texas, to gain a firsthand perspective.”

Organizers hope that participants will eventually transform their business models into technology-centric startups for the greater good. Indeed, the showcase has given birth to several nascent companies with real potential. HonestFi, a 2017 MFC participant, for instance, designs a mobile application to provide financial services, including check cashing, fund advances, and prepaid cards, to low-income Americans.

In recent years, USC Viterbi has become a burgeoning center of innovation and entrepreneurship. With the Maseeh Entrepreneurship Prize Competition, the National Science Foundation Innovation Node (“I-Corps”) headquartered on campus, the USC Coulter Translational Research Partnership Program, and the USC Viterbi Startup Garage, students have many opportunities to develop innovative business models and explore the commercialization of technologies.

The Min Family Challenge plays an integral role in the school’s nascent innovation ecosystem, USC Viterbi Dean Yannis C. Yortsos said.

“MFC is likely among very few, if not the only one in the world, that challenges engineering students to solve important societal issues using engineering ingenuity,” he said. “It appeals to the better angels of our nature and helps instill a wonderful mindset of societal consciousness to our students, one that will help them change the world.”