The Al Dorman Way

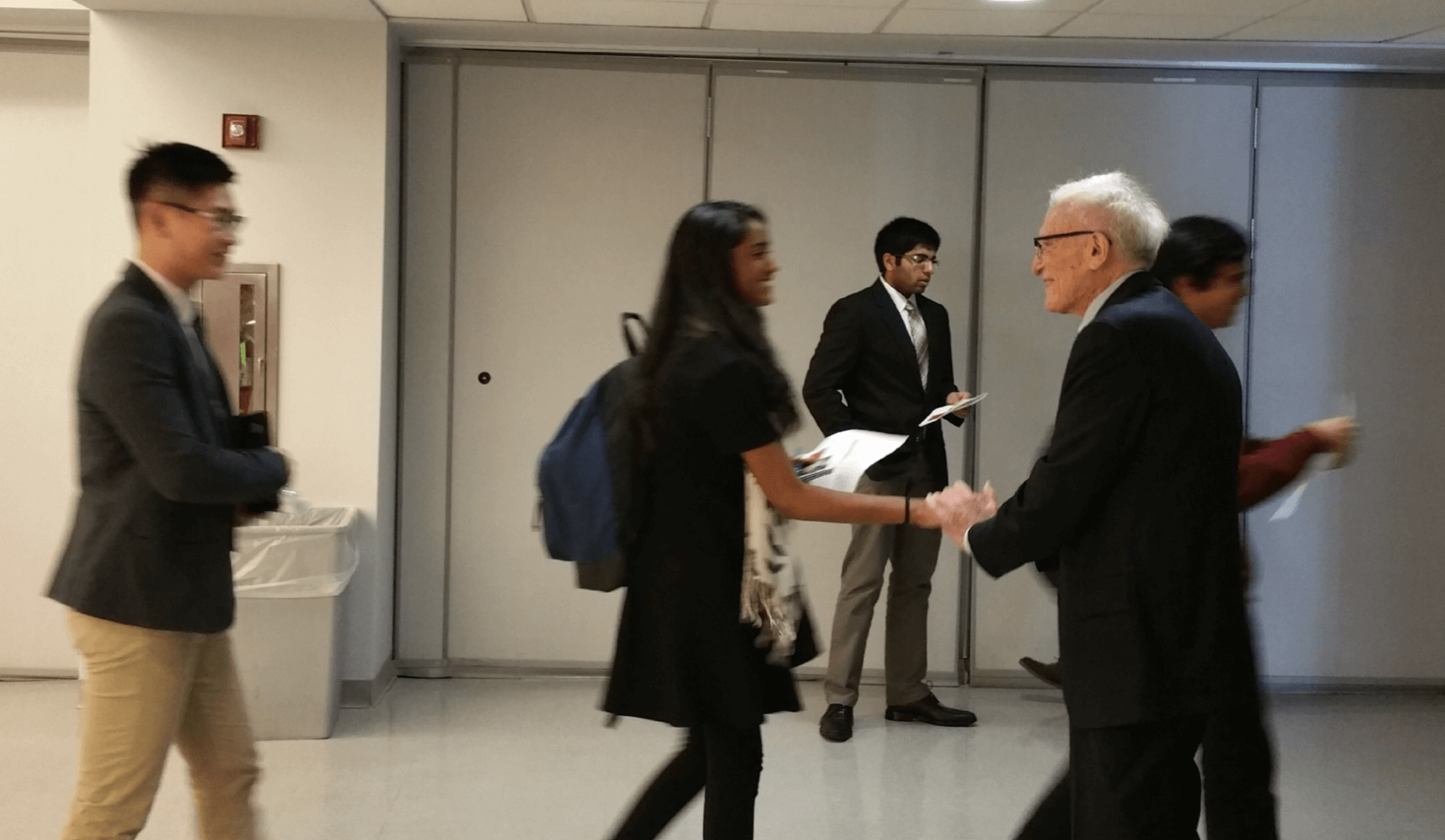

Albert Dorman, M.S. CE ’62, has shaped cities. His signature and civil engineer’s stamp are on the original plans for Disneyland. He was the founding chairman and first CEO of AECOM, a fully integrated global infrastructure firm that employs 90,000 people and serves clients in more than 150 countries, generating $18.2 billion in revenue in 2017 alone. Fortune magazine has listed it among its “World’s Most Admired Companies” for four consecutive years now. In 1995, Dorman, who is also a member of the National Academy of Engineering, endowed the Albert Dorman Honors College at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, from which he earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1945. The Honors College was ranked by the New York Times in 2017 as the best college in the country for raising students from the bottom fifth of the income distribution who end up in the top three-fifths. But search for Al Dorman’s name written in stone, and you’ll search in vain. The man doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. “I’ve said everything I had to say,” he said. “Is there anything left to add?” At 92, Al Dorman has a lot more to add. For one, he desires people to live the best versions of themselves. When we do, he believes, we will inspire others to live the best versions of themselves.

You grew up in a small town in rural New York. How has that shaped who you are?

If you’re practicing in a city of millions, you can cheat somebody every week and get away with it. But if you grow up in a town of 3,000, the way I did, say one word that’s wrong and everybody in town knows it. You’re careful what you say and what you do. The guy who pumps your gas is as important to you as the banker in town, as the doctor in town. You hope you can get along with very different people and understand their views.

Were you handicapped in any way by your small-town upbringing?

A handicap I had was always being too young. I was a college senior at 18. To try to compete athletically and intellectually with people two and three years my senior and to try to gain their respect was quite an issue. Fortunately, I was tall and strong for my age. My upbringing helped me when I opened my then one-man civil engineering practice in 1954 in a predominantly farming community in Hanford [California] in the San Joaquin Valley. Hanford, which now numbers over 55,000, was then a city of roughly 10,000. I was subsequently the city engineer for the two other cities in Kings County, Corcoran and Lemoore, then some 5,000 and 2,500 people, respectively. They were too small to require a full-time city engineer, so I came on as a consultant. But my family and I integrated into those communities. I eventually assumed leadership roles in Kiwanis [a service organization], the Kings County Community Concert Association, and school design and public library activities, among others.

Since then, I’ve devoted my life to a broad variety of things where I thought I could make a difference. For example, at the Gladstone Institutes [a research organization dedicated to using visionary science and technology to cure unsolved diseases], I was one of three trustees for some 25 years. I retired from that just a year ago, and in those 25 years, only three of us were ultimately responsible for all financial, academic and managerial matters. We started with 20 people and ended up with 500 in a world-renowned research center, in which one of our scientists [Shinya Yamanaka] won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Another source of great pride to me and my family is the Albert Dorman Honors College. Unfortunately, it has my name attached to it. And that was only because the president of the university thought having my name would help it grow.

Why did you agree to establish the Honors College?

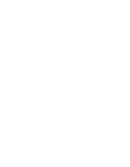

The concept of the Honors College was to find very smart young people, the top 2 percent, who were overlooked. Over half of them came from homes where English was not the first language. There’s a moment that brought tears to me and my wife that typifies what I’m talking about. My wife and I were visiting the college, as we do twice a year, and this young African-American man came up to us and said, “I live in Harlem in a two-room apartment. I have four brothers and sisters, none of whom have graduated high school. I don’t know who my father is. My mother works two shifts to support the five kids. This year I’m graduating from the Honors College, and I’ve been accepted to graduate school at Carnegie Mellon.” Now, to me, that is a greater reward than almost anything. That’s why the “Albert Dorman” isn’t the important thing. It’s the “Honors.”

Why are you so reluctant to put your name on things?

Well, there’s a story I sometimes tell that may help you understand. AECOM now has a new building in downtown Los Angeles with its name on top of it. My wife and I went to visit it, and we stopped on the first floor and I said to the security guard, “I’d like to go up and visit the new quarters of AECOM.” And he said, “Who are you?” And I said, “I’m Albert Dorman.” And he said, “You’re not on our list.” And I said, “Well, would you call upstairs?” So he called upstairs and they said, “We don’t have you on the list.” Finally, I said, “Can you find some old-timer?” And they found somebody who all of a sudden rushed down to greet the founder of the company. You see (smiles), now that’s a tribute.

How do you spend most of your time now?

I spend most of my time mentoring people. Currently, I’m mentoring probably six to eight leaders of prominent organizations, and what I mean by mentoring … let’s say you were the president of, pick a school or a company. Who can you talk to that doesn’t have an agenda? The board of directors? You may have friends on the board, you may have appointed some of them, but they have an agenda. Early in my life I discovered that I needed to find somebody who I respected, who had some experience and brainpower but had no agenda. We all have our parents, our wives, husbands, or our favorite friends, but all of them have agendas — some good ones, like taking care of your health or spending more time with your family. Find someone you respect without an agenda and talk to them.

Can you tell me something that’s true that almost no one agrees with you about?

I don’t know if it’s true or not, but on rare occasions, I get invited to talk to M.B.A. students, and I propose a different kind of thinking. I tell them, “Identify your strengths and weaknesses.” As an example, I use General Electric, which had Jack Welch as its CEO for many years. When he retired, they tried to find another CEO like him. I think that’s a terrible mistake. What you have to say is, “What were Jack Welch’s weaknesses?” Find someone who will patch them.

That’s what I did at AECOM. My weakness is that I’m not particularly interested in money for its own sake — although the company and its predecessors never had a loss year while I was CEO. I’m interested in projects and in making the world a better place. So, I picked a successor whose desire was to make the company bigger and better and more profitable, in addition to the goals I had established. When I was a small, one-man office in the San Joaquin Valley, I said to myself, What do I hate and what do I like about what I’m doing? You usually like what you’re good at, and you’re usually good at what you like. And you’re usually bad at what you don’t like to do. I disliked going to a client that I had done a lot of work for to say, “When are you going to pay your bill?” My answer was not to change myself but to get somebody who was tall and weighed 200 pounds to pay them a visit and say, “Al’s wondering when you’re going to pay your bill.” (laughs) It’s a crude example, but you have to know yourself.

In 1954, Walt Disney chose you to be the civil engineer who would help him build Disneyland. You were 28. How did you deal with that kind of pressure?

I don’t want to say much about that because it was so long ago, and I don’t want my recollections to cloud the reality of those events. I do remember that the Mark Twain steamboat was a frightening thing for me to work on because paddlewheel steamboats hadn’t been built in the U.S. for many years, and nobody had ever designed a paddlewheel boat that rode on a rail.

You could have simply said no, thank you.

I can’t say “no, thank you” to any major challenge. I can say I’ll do my best. But I can’t say no, thank you, unless it’s going to kill me or it’s ethically questionable. If I had done that, I wouldn’t have ever gotten anywhere in life. But the project almost killed me. I couldn’t go back to the park for 10 years after it opened. I made the final inspection one week before it opened on July 17, 1955, then I didn’t set foot in the park for 10 years. I worked night and day, seven days a week continuously. But how can you turn down an opportunity like Disneyland? Though I should have, because if anything had gone wrong, here I am, a 28 year-old kid, my whole professional life ahead of me could have been ruined. But fortunately, my partner, Sam Hamel, a brilliant mechanical and electrical engineer who had worked on the 1939 New York World’s Fair, was the real leader of the team and wouldn’t let me do something too dumb.

When have you been most satisfied?

My wife, Joan, would say I’ve never felt fully satisfied. One story I remember, when I left AECOM [then a private employee-owned company], I gave all my stock to the employees: that is, I sold it at the then book value. I saw I wasn’t going to be actively contributing anymore, so why should I continue to benefit from its future growth. But my great satisfaction came from my company driver, who’d been working for me for some time. Much later, he came to my office and said, “Mr. Dorman, I want you to know that my son is in college now and we own a home and every bit of it is a result of you giving me this stock.” Now, that’s like the Honors College, it really brought tears to my eyes. When I’ve made a difference, when I’ve helped shape ways of thinking, that’s satisfying.