Helping Hands

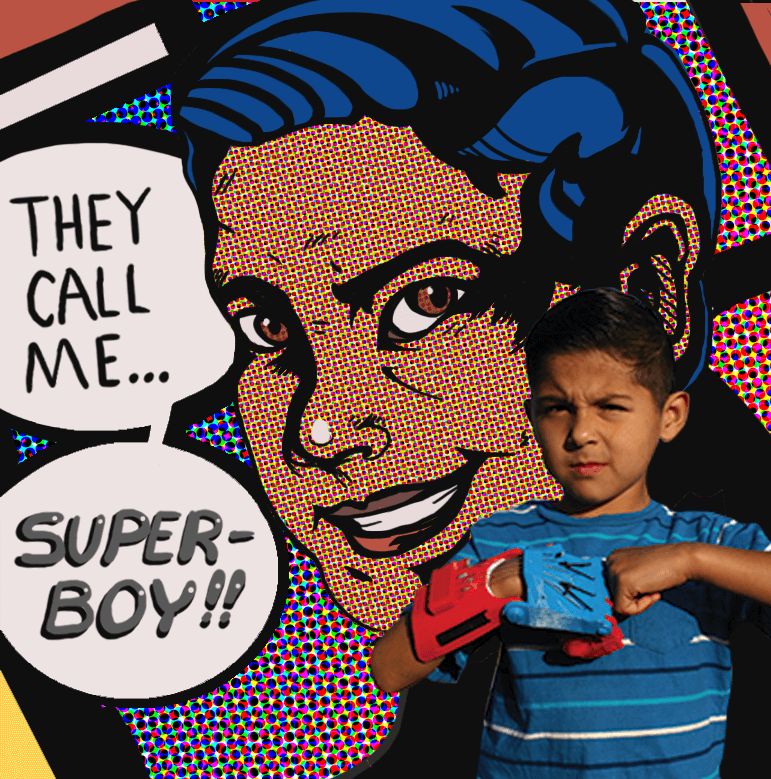

Six-year-old Jonny Maldonado was once bothered when people gawked at his unconventional right hand, but now he feels like a superhero when they stare at his little palm.

Jonny has symbrachydactyly, a congenital abnormality that gave him a tiny right hand with only a thumb and pinky finger. His brother, 8, and sister, 14, were both born without the condition.

“At first we were kind of worried,” Jonny’s father, Daniel Maldonado, said. “But we’re a family of faith, and we believe that he was born like that for a reason — that he would be an inspiration to kids, and he would function like any other kid on the playground and in school.”

Jonny used his tiny two fingers as “pinchers” to do everything he needed to do. Nevertheless, his right hand attracted “bad attention” that bruised his self-esteem. Not long ago, Jonny came home from preschool perturbed.

“Kids were just curious,” Maldonado said. “They just followed him and asked him, ‘Why is your hand like that?’ He did come home a couple of times and expressed to us that he didn’t want that hand.”

But Jonny recently stopped feeling so vulnerable thanks in part to students at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering. USC 3D4E, an on-campus 3-D printing club, has collaborated with Children’s Hospital Los Angeles to give him two free 3-D printed prosthetics every year.

The first USC hand, tailored to meet Jonny’s needs, arrived in May. Each prosthetic costs about $25, said Alison Glazer, a USC Viterbi mechanical engineering undergraduate student and 3D4E president.

Daniel Maldonado believes the opportunities 3-D printed prosthetics will offer Jonny are limitless. A pre-USC “robo-hand” prototype the kindergartener received in December works well enough, but Maldonado imagines the plastic appendages will become more functional as breakthroughs are made.

“It’s going to impact his life,” Maldonado said. “It’s amazing what they’re doing with these 3-D printers. It’s a true blessing for us, and I know it will be for many other kids.”

Early in Jonny’s life, he underwent reconstructive surgery to reposition his two right fingers from a surfer’s “hang loose” hand gesture to a “rock on” sign. And that’s what Jonny did, his father said.

“He’s actually proven far beyond our thoughts of everything he can do,” Maldonado said, beaming. “He plays T-ball, he’s played soccer, he can hang on the monkey bars. He’s shocked and impressed us! It was a learning process for us to say, ‘Hey, he’s different, but he can do everything.’”

Still, people rubbernecked when they saw Jonny’s pincers. Then late last year, the young boy’s life began to change. He received a free 3-D printed hand from a teacher in North Carolina. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles taught Jonny that flexing his forearm toward his body closes his prosthetic so he could grasp things. Jonny quickly became enamored with his “robo-hand.”

His classmates still gazed, but he doesn’t mind now, he said, especially when they ask him, “Where did you get that hand?”

The 3-D printed prosthetic has given Jonny a confidence boost.

“The first day he took it to school, all the kids just swarmed around him,” Maldonado said. “They even wanted to play with it. They wanted to put it on.”

As his father spoke, Jonny beamed, tilted his head and flexed his forearm. His red-and-blue hand opened and closed.

“Some people say, ‘I want one of those!’” Jonny said grinning. “I’m glad I have it. I wear it when I need it. I pick up big objects. I can pick up a bottle and a ball. I think it’s really cool. I like the colors — because it’s a special hand.”

When he has it on, Jonny said he feels like his favorite superheroes: Iron Man and Captain America. Then he twisted his body and — with a bashful twinkle — said the colorful prosthetic makes him feel like Superboy.

With his pre-USC prosthetic, Jonny could pick up cups, ride a bike, and throw a ball. Yet he doesn’t wear that one often because it’s uncomfortable. It wasn’t printed to meet Jonny’s specific measurements.

The ones that USC Viterbi has given Jonny, however, are designed especially for him. The unique collaboration started when Kara Tanaka, a post-graduate premedical student at USC and creator of the USC Freehand Project, told a doctor at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles that 3D4E would like to donate plastic prosthetics to patients there.

In addition to the local hospital, 3D4E’s USC Freehand Project has sent a dozen prosthetic hands to Haiti and another dozen to Syria since November. Half of them were made using AIO Robotics’ Zeus, the world’s first all-in-one 3-D printer. AIO Robotics has donated two Zeus printers and rolls of plastic filaments to 3D4E.

Zeus was the brainchild of Jens Windau and Kai Chang, two USC computer science doctoral candidates. The pair began their profitable startup with funding from a Kickstarter campaign and the Viterbi Startup Garage, the first Los Angeles accelerator for engineers backed by an influential university.

Funds for the prosthetics came from 3D4E membership dues and donations from alumni, public schools and private companies.

Jonny’s next hand — he playfully refers to it as “the Batman hand” — is the Cyborg Beast and will be made of ABS plastic with stainless steel screws. This “robo-hand” was printed just for Jonny and will give him better grip because gel-like tips have been added to the fingers.

Daniel Maldonado said he appreciates USC’s lifetime supply of helping hands.

“I think it’s great what USC is doing,” he said. “Keep doing it because there are so many kids that don’t even know this technology. There are so many kids that could benefit from it. We just need to find them.”