Rethinking Refugee Camps

USC Viterbi undergraduates Stefani Mikov and Emir Ucer want to fundamentally transform the structure of and improve conditions in Syrian refugee camps in their home country of Turkey.

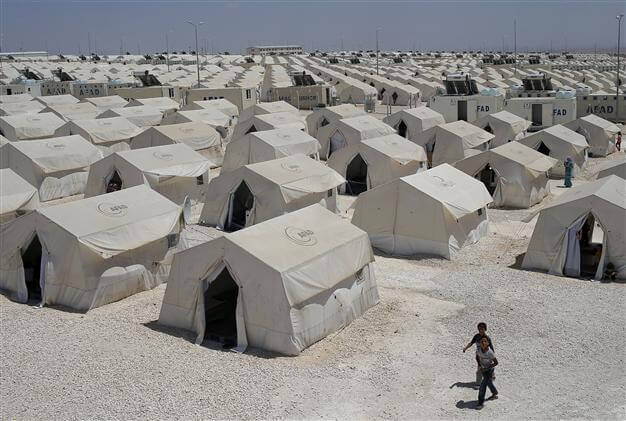

“Refugee camps should typically house 20,000,” said Mikov, a senior who is double majoring in industrial and systems engineering and piano in the USC Thornton School of Music. “Right now, camps in Turkey are holding about 6,000 more than that. Without proper sanitation, plumbing and medical resources, that means that diseases spread rapidly.”

With nearly 3 million Syrian refugees in Turkey and little sign of the Syrian conflict abating, the international community has thus far been unable to coordinate to set standards and plans for refugees to survive, let alone thrive. However, Mikov and Ucer’s plan may rectify that.

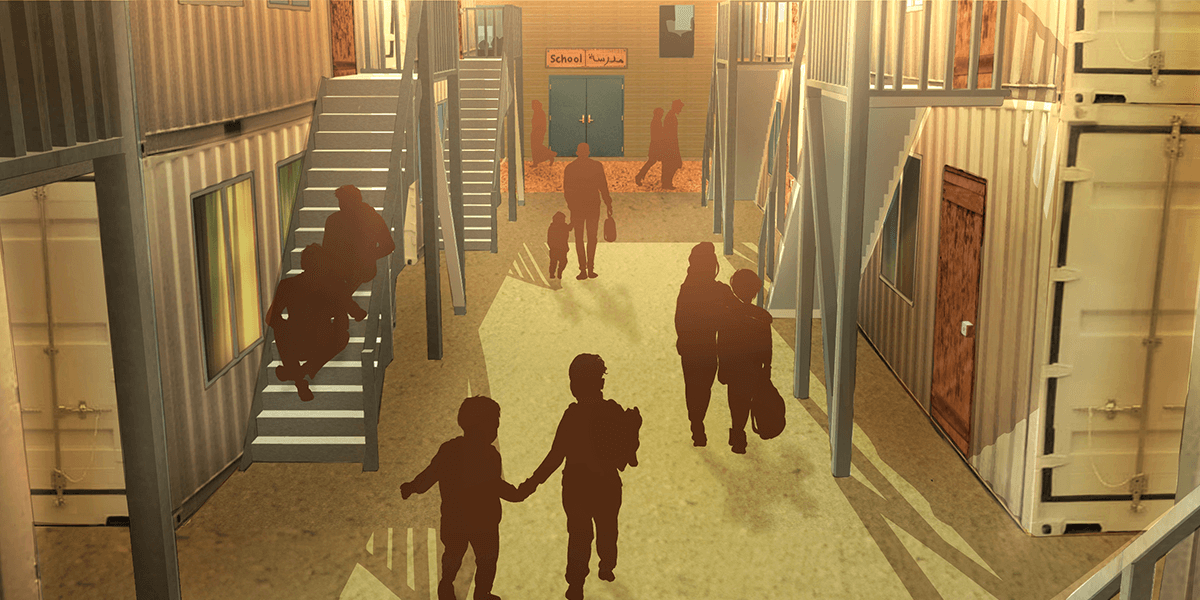

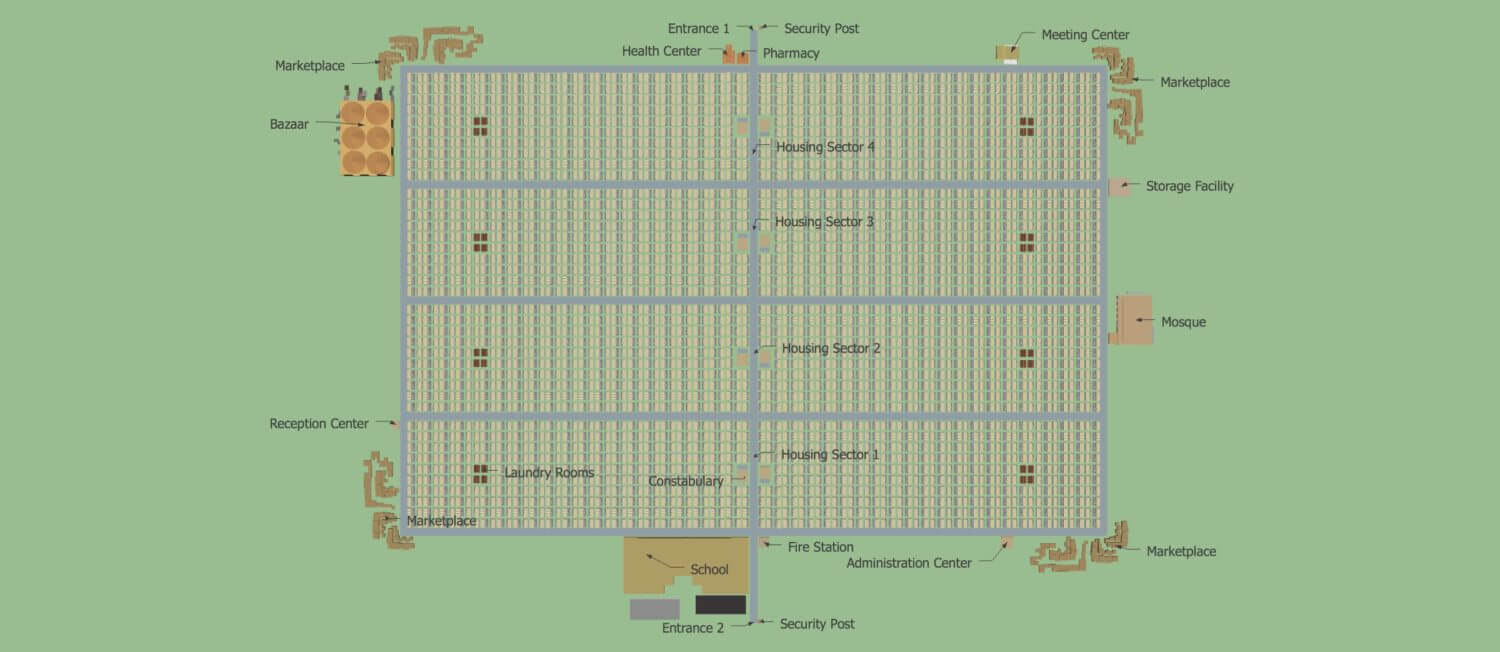

Complete with a fire station, a pharmacy, a clinic, a religious center, internal security and even a school to teach academics and Turkish to Arabic-speaking Syrians, Mikov and Ucer’s meticulously sized redesign is built around the idea of a refugee camp as a transition place.

“Many of the refugees suffer from trauma once they make it to safety,” said Ucer, whose research with Mikov revealed that over half of refugees suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and nearly one-third suffer from depression. “Although our plan includes therapists in the health center, we also included a mosque for men who won’t seek psychological health [counseling] for cultural and religious reasons.”

The pair’s redesign also maintains internal regulation, with security stationed in each of the four, 5,000-person housing sectors requiring fingerprinting. In addition, Ucer and Mikov explicitly designed multiple markets throughout the camp to keep prices low and supply high through competition.

“It’s so refreshing to see undergrad students like Stefani and Emir so socially and globally conscious, willing to apply their education to solving wicked problems that are truly among the world’s grand challenges,” said Najmedin Meshkati, professor in the Daniel J. Epstein Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering and a former U.S. State Department Jefferson Fellow. “Their fresh, outside-the-box perspective is not always readily available to those in power charged with managing the refugee crisis. I really think they’re the embodiment of a badly needed and sought after global engineer.”

Scouting for a suitable location remains one of the most complex challenges for the establishment a refugee camp.

“We can’t have a camp too close to a war zone, and absolute safety is very hard to achieve as long as the U.N. refuses to create no-fly zones that could protect the people,” said Ucer, a senior majoring in industrial and systems engineering.

Mikov and Ucer are trying to get their research published in “Ergonomics in Design,” a peer-reviewed quarterly, with an end goal of having their work featured in a Turkish newspaper. They hope their plan eventually reaches the Turkish ministries, which have been in charge of building refugee camps.

“I’ll call my parents in Istanbul and I ask them what’s really going on with both the diplomatic and humanitarian crises, and they say that they don’t even know,” Mikov said. “No one knows what’s actually happening, so we’re hoping for the best at this point.”