The Time Machine

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…

Humanity has long dreamed of peering into the past to gain a better understanding of how we got here, where we’ve been, and where we’re headed. Until now, no machine existed that allowed us to time travel to the beginnings of time.

That is all about to change.

When launched in October 2018, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will allow us to understand the universe as never before. The most powerful space telescope ever built will give scientists a view of the first galaxies and stars forming in the darkness over 13.5 billion years ago, 200 million years after the Big Bang. In essence, it will allow astronomers to glimpse the end of space’s dark ages and the birth of the universe, as we perceive it today.

The Webb telescope, successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, might also answer the question as to whether we’re alone in the universe. That’s because it will observe smaller exoplanets – planets that orbit a star other than our own sun – and ascertain whether they have Earth-like atmospheres with life-supporting oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water vapor.

“We’re enabling a new dawn of discovery,” said Scott Willoughby, M.S. ’91, the vice president and program manager for the James Webb Space Telescope at Northrop Grumman. “We’re creating an instrument that will allow us to see things never seen before. We have a chance to say whether there’s Earth 2.0 out there.”

To gain an appreciation of the Webb telescope’s potential, it is worth noting just how far Hubble has advanced our understanding of space since becoming operational in 1990. That telescope played a major role in the discovery of dark energy, a little known force that contributes to the expansion of the universe by working against gravity. Hubble also helped determine the age of the universe and has captured images of ancient galaxies in all evolutionary stages.

The $8.8 billion Webb telescope, overseen by NASA and 20 years in development, represents an international collaboration of 24 countries, with significant contributions by the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency. It is named after James E. Webb, NASA’s second administrator from 1961 to 1968 who played an integral role in the Apollo program.

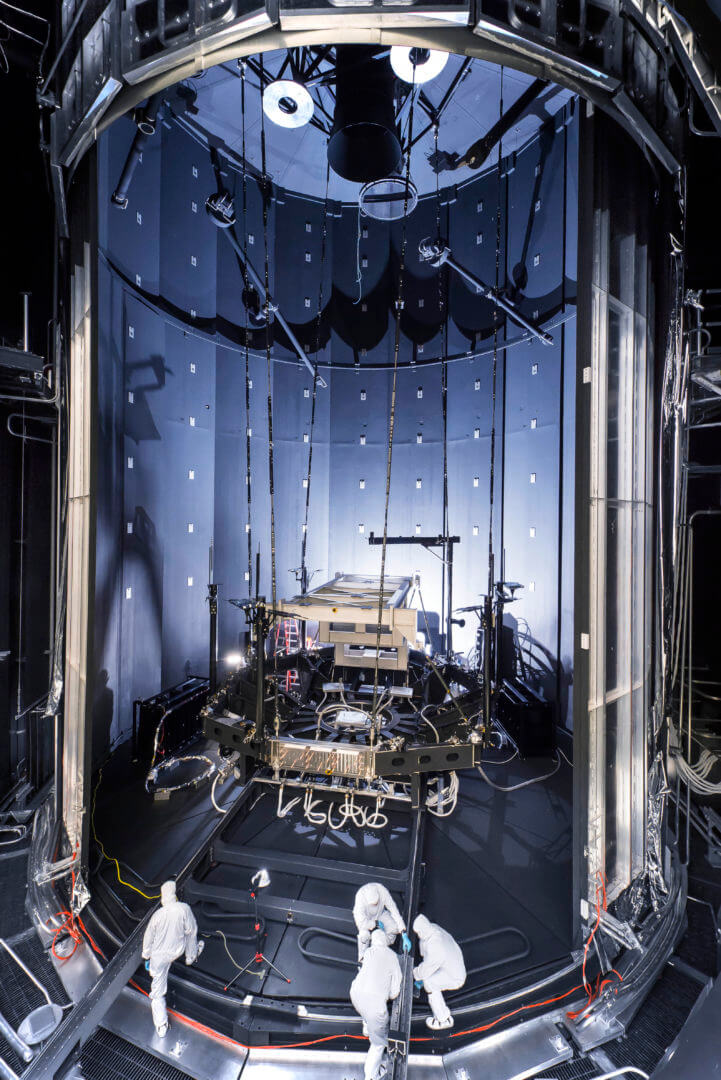

In 2002, NASA selected Northrop as the prime contractor to develop the telescope – a major victory for the Falls Church, Virginia-based aerospace firm. The company is designing and building the Webb telescope’s deployable sunshield; providing the spacecraft that will carry the telescope into space; and integrating the entire system. Northrop-led teams, in collaboration with subcontractors, developed the Webb telescope’s mirrors, composite materials and other systems.

USC Viterbi and James Webb

At every phase, USC Viterbi alumni have played an integral role.

The entire project falls under the portfolio of Tom Vice, B.S. AE ’93, Northrop Grumman corporate vice president and president of the company’s Aerospace Systems sector. “The most exciting thing is trying to imagine what we will learn that we haven’t even dreamed about yet,” he said.

Willoughby, as project manager, directs nearly every aspect of the endeavor, ranging from technical issues to budgeting to briefing Congress – “I get up every morning and ensure that we have a plan that’s comprehensive and that each day we mark and measure ourselves and get those steps done,” he said. Supporting him is fellow Trojan and Deputy Program Manager Gus Makrygiannis, MBA ‘92. Among the engineering teams designing, testing and integrating the telescope are scores of USC Viterbi alumni.

The engineering school is so well represented because of the quality of its graduates, Willoughby said. “At USC, I learned how to solve, think about and approach problems and not be intimidated by them,” he said.

Scientists believe the Webb telescope has the potential to revolutionize astronomy. By capturing images never before seen, it will deepen our understanding and knowledge of the evolution of galaxies and the formation of planetary systems and stars. The Webb telescope will have the capacity to detect objects that are 10 to 100 times fainter than Hubble can currently see, experts said.

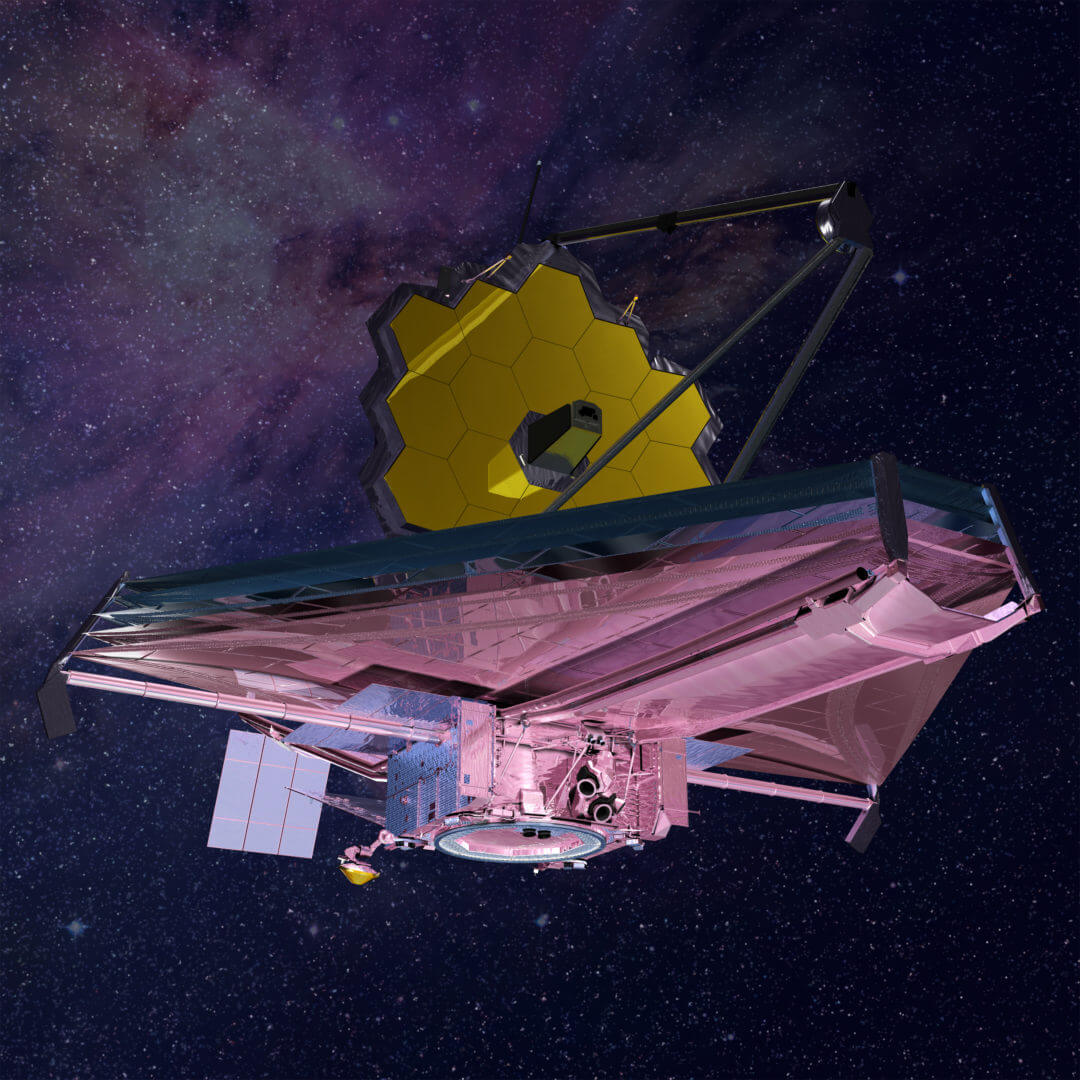

The telescope will reside in a point in space nearly 1 million miles away called L2, where gravitational forces will enable it to rotate around the sun in the same orbital period as Earth. By contrast, Hubble lives only 250 miles from earth. It will take the Webb telescope 30 days to reach its final destination.

The Webb telescope, by being so far away, will escape the sun’s and earth’s thermal heat, making it possible to capture images in the infrared – “where all this historical knowledge about the universe is,” Willoughby said. Because the universe expands the farther one goes back in time, the early light scientists want to capture falls outside the visible light spectrum, necessitating an instrument that can measure light in the infrared range.

Additionally, the telescope’s location will keep its mirror a cool -388 degrees F, a prerequisite for working in the infrared spectrum.

A Marvel

The Webb telescope is a technological marvel.

When it comes to space telescope mirrors, bigger is better. That’s because larger ones gather more light, allowing them to see fainter objects. Their higher magnification also permits them to identify finer details.

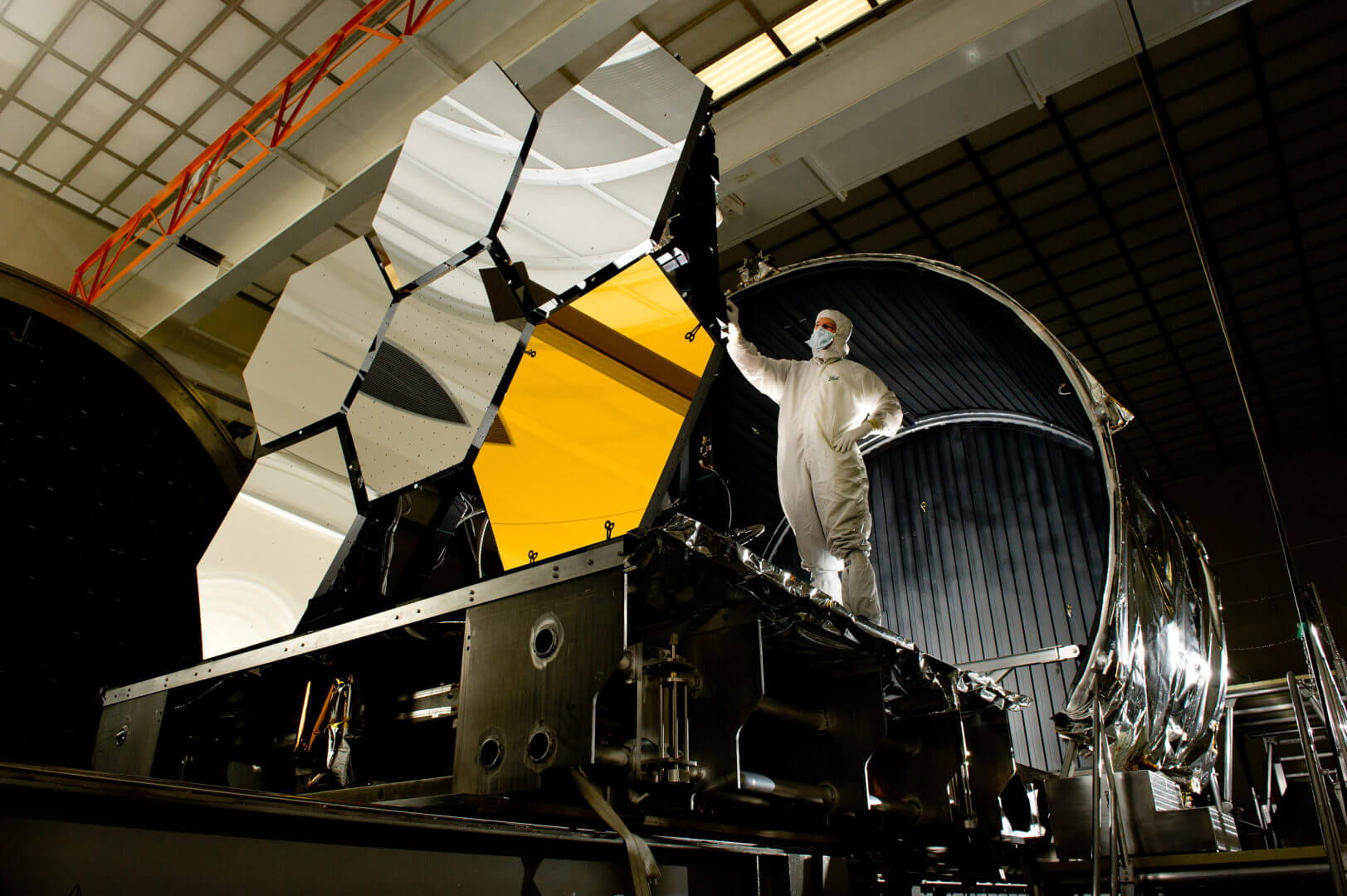

At 21-feet-4-inches, the Webb telescope will become the biggest ever launched into space, featuring a collecting area about seven times larger than Hubble’s. With its deeper infrared sensors, the Webb telescope can better penetrate gas and dust to see more and older stars and galaxies.

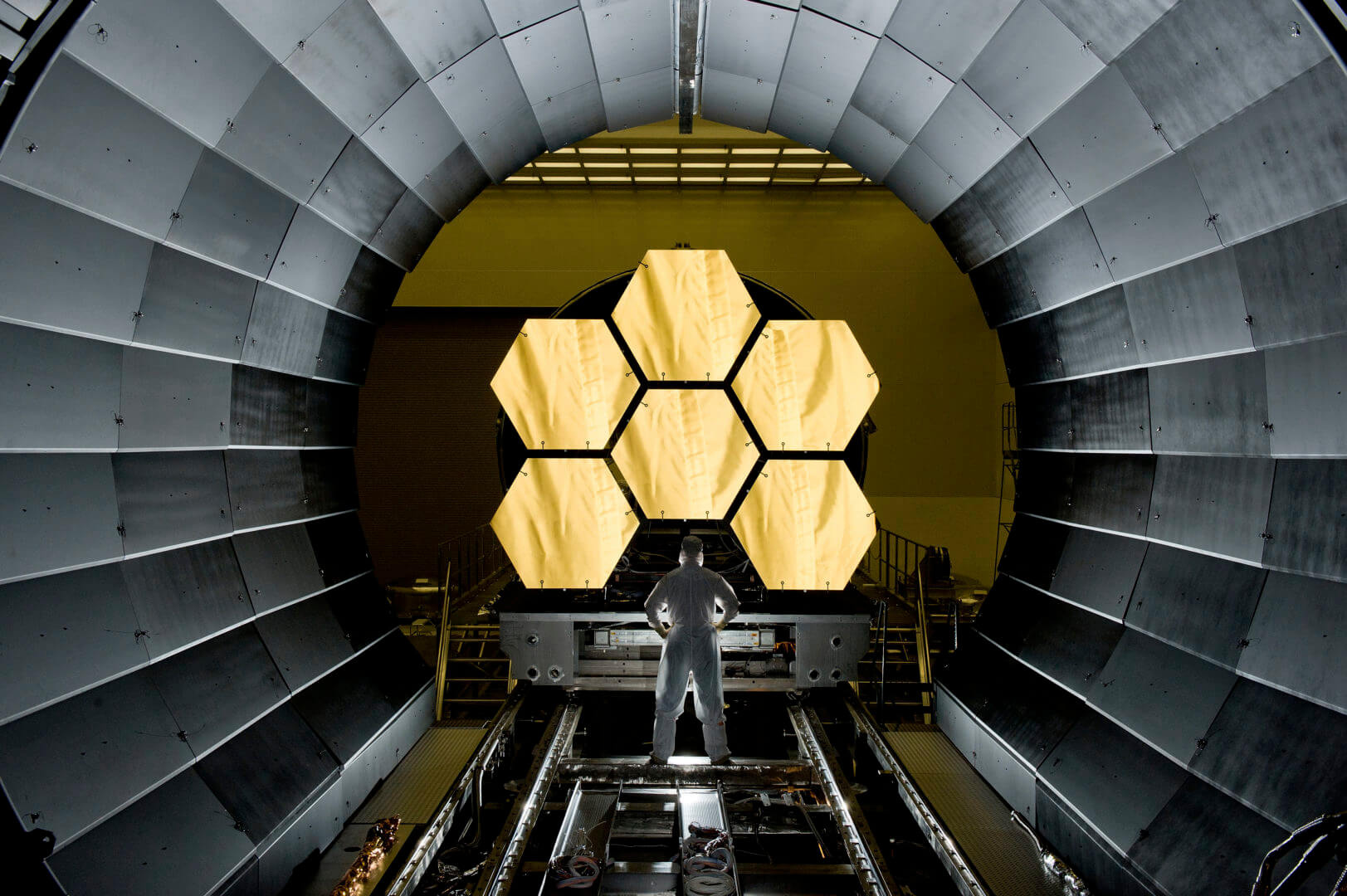

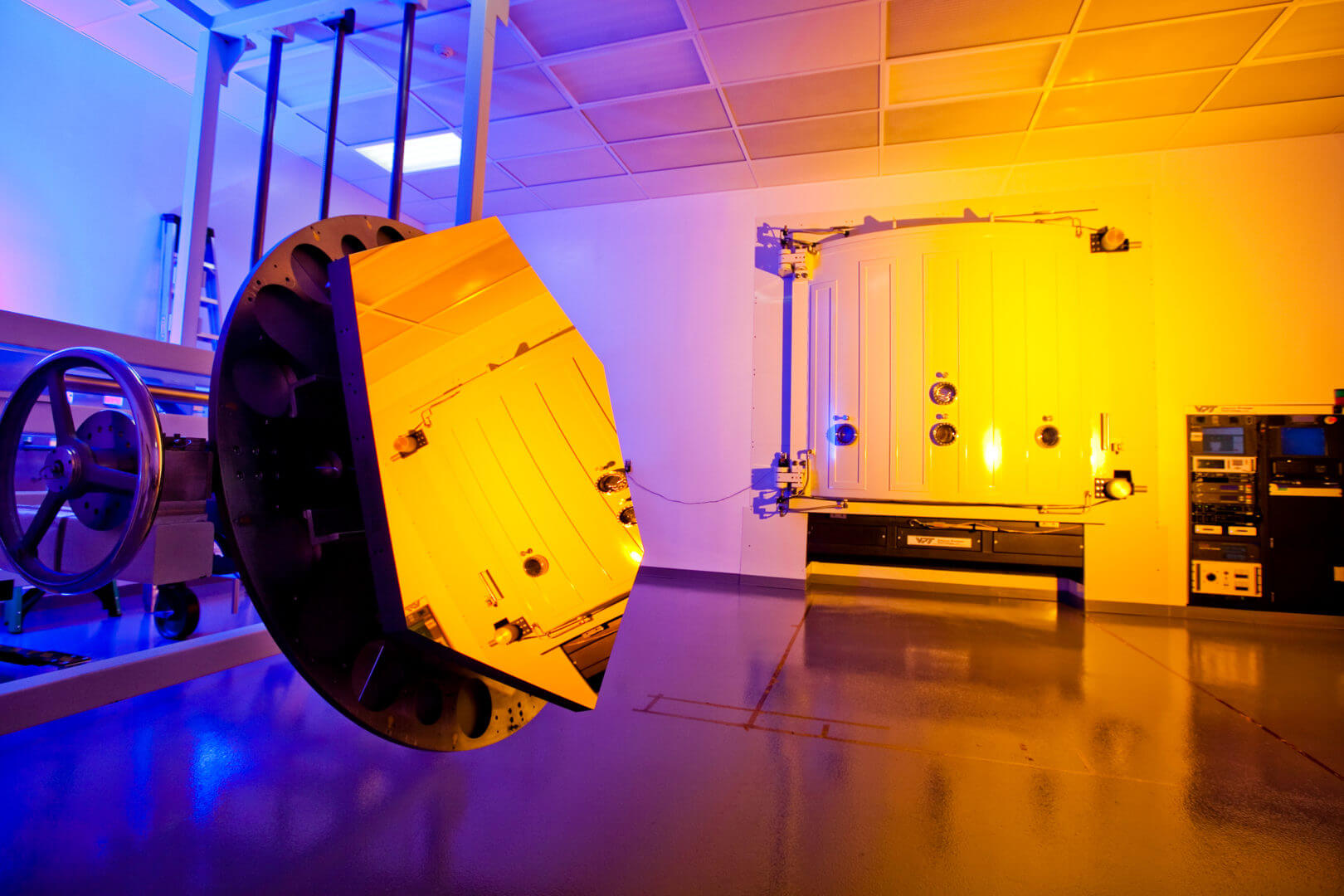

Project engineers working on the Webb telescope’s primary mirror needed to build it light enough for a rocket to carry into space but compact enough to fit into a small area. They have addressed the weight issue by making the mirror from beryllium, a rare metal stronger than steel but lighter than aluminum. A thin layer of gold coats its surface to reflect the infrared light.

Making the huge mirror small enough to fit into a rocket required an equal amount of ingenuity. Engineers have done so by building it from 18 hexagonal-shaped mirror segments that fold for transit but will unfold like origami at the final destination. Computer-controlled motors behind the mirror segments will slightly bend them as needed to ensure that they remain in focus.

“It took eight years to make such a segmented mirror with such incredibly precise shapes,” Willoughby said.

Protecting the mirror from the sun’s scorching heat and space’s frigid cold will be a giant sunscreen measuring 80-feet-long, by 40-feet-wide, about the size of a tennis court. The five-layer sunscreen is so thin – each layer is between 1/1,000th to 2/1000th inch thick – that it can “stow like a parachute and deploy into orbit,” Willoughby said.

After Northrop engineers assemble the entire observatory – telescope, instruments and spacecraft – it will be transported to French Guiana. An Ariane 5 rocket will launch the system into space.

Willoughby cannot wait.

“We had to build a telescope bigger than ever before, operating in a colder environment than ever before and at a distance farther away than ever before,” he said. “This has never been done before.”