Forging Iron [Wo]Man

“I don’t know anything about your world, but I do know machines.”

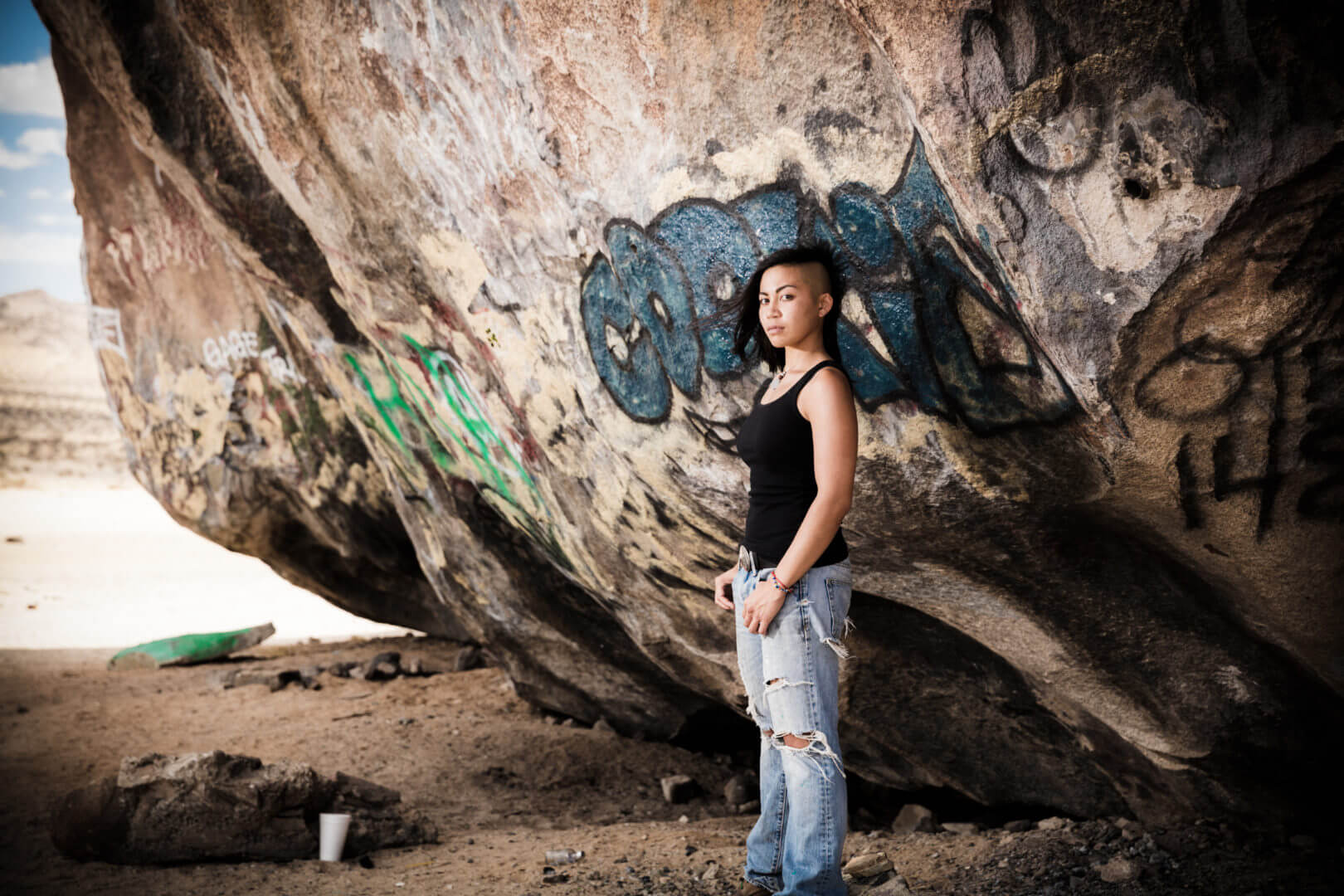

Samantha “Sam” Huynh sat across from Terence Sanger, USC Viterbi provost associate professor of biomedical engineering, neurology and biokinesiology. Her half-hawk, hair hanging over one side of her face, gave her a punkish edge.

In fact, just about everything about Huynh — hair, eyes, personality — gives her an edgy appeal. She’d just graduated from USC Viterbi with an M.S. in materials engineering. Now she was hoping to join Sanger’s Ph.D. students.

What was a mechanical engineer doing considering biomed? Gates Millennium Scholar, stints at Tesla Motors and SpaceX. Glancing over her C.V. one last time, it occurred to Huynh that she’d been working on engines all her life. Now she wanted to work on bodies?

“I can teach you what you don’t know,” replied Sanger. “You can learn control systems. I need someone who can work with their hands.”

To understand Terence Sanger, just take one part electrical engineer, two parts child neurologist, add a little Tony Stark, and stir. Sanger’s lab is known around the world for helping children with cerebral palsy, dystonia and other movement disorders regain control of their bodies by building artificial spinal cords, controllable prosthetics and exoskeletons.

Sanger looked up from her CV, impressed. But there was one inevitable question: “Why do you want to do this?”

Huynh paused, drawing her breath.

“Because I want to help my friend walk again.”

She had Sanger’s undivided attention.

“Welcome aboard.”

With that, Huynh’s story had reached a new summit — a story of iron will and surmounting iron gates, of breaking limits and defying stereotypes and the quest to build the ultimate Iron Man.

Her parents escaped to America from Vietnam and Cambodia as bombs rained over their villages. A New Mexico couple, Herb and Dorothy Beard, took them in on their farm. The Huynhs were the only Asian family in Belen, a railway town of about 7,000 whose name is Spanish for Bethlehem.

Herb Beard taught young Sam Huynh about engines and horses and how to spit proper. Before she could even walk he’d take her out at the crack of dawn and put her up on a horse. When she fell, he’d say, “She’ll walk it off. That girl’s a force of nature.”

Herb confided in her, often without words, and when he didn’t turn up one evening, she knew at once that something was wrong.

“They found him dead on his horse,” remembered Huynh. “He broke his neck and just died in the saddle, died doing what he loved.”

In her Ford Ranger, Herb smiles from her sun visor in the quiet way that only a photograph can.

To keep her out of trouble, Huynh’s father got her a job at the mechanic’s shop where he worked. “It was my dad’s way of separating his feral wolf of a daughter from the confines of civil society,” she said.

Ironically, the shop guys all brawled to pass the time, she said, and they taught her how to brawl too. She excelled at mechanics and at busting teeth. When work was slow in the shop, she raced cars in the desert. She fed her soul with painting and poetry.

But she wanted something more. “And I wanted to show every teacher who didn’t think I’d make it out of Belen just how wrong they were,” she said.

She chose to study mechanical engineering at the farthest university from everything she knew, Rochester Institute of Technology.

The upstate New York lifestyle was crisp and precise. People left their cars in gleaming service centers. Huynh never saw anyone spit.

One night, in a bad side of town, a guy trapped her inside a dingy bathroom. “Little did he know he was messing with a real-life American cowboy. I never leave home without my tools,” she chuckled.

The encounter, coupled with high-velocity engineering school and a yearlong battle with illness, made her feel invincible, like she could get through anything unscathed. “That girl’s a force of nature,” Herb’s voice rang in her head.

Then one night, in late 2010, Sam collapsed. In the literal sense.

“My body is betraying me,” she wrote in her journal. “I can fix machines. It means nothing in regards to the mechanism of the human body.”

She struggled to keep up in her coursework and kept her private battles hidden from loved ones. She didn’t want to return home and “crush their dreams,” she said.

Feeling a sense of suffocation in Rochester, Sam dreamt of going somewhere where “you couldn’t see the stars at night… where stars walk by you every day,” she imagined.

“They say you can’t see the stars in L.A. because they’re all around. People pouring into this basin, chasing moonshots. I want to be a part of that,” she said.

She landed a mechanical engineer’s dream job as a prototype machinist’s assistant and later design engineer at Tesla Motors. Huynh worked on the Tesla Model S, then interned as a propulsion engineer at SpaceX, helping to design the Draco capsule. She was part of a team of architects behind the fuel systems that give the International Space Station its payload.

Then one day, the phone rang. A friend from RIT, Taylor Hattori, had crashed his dirt bike and was in the hospital. The news was bad. He was paralyzed from the chest down.

Huynh jumped on the first flight to Albany.

“When I saw his shoulders slump at the futility of everything — he couldn’t even lift his arm — it just tore me up,” she recalled. She told him, “I’m going back to L.A. and I’m going to figure out a way to fix you.”

“I don’t want to be your thesis.” Hattori snapped.

“Too bad. It ain’t just about you.”

Huynh set her sights on a master’s at USC Viterbi, where she envisioned building a new body for Hattori and so many people like him.

“I knew the materials profs at Viterbi were by far the best in the country, and I wanted to vertically integrate all that theory with my mechanical abilities,” she said. Soon, she was getting her hands on some pretty cool technology, from quantum electronics to nanotechnology to biomaterials and tissue engineering.

One thing that really hooked her was the exoskeleton system — a frame with joints corresponding to those on the human body, allowing humans to perform feats of strength previously confined to comic book characters. The real Iron Man.

In the Sanger lab, Huynh wants to take advances in exoskeletons, such as ReWalk, to the next level.

“Ideally, I’d like to lend mobility to those unable to walk at an equal scale to those who can,” she said. “My research is also focused on dexterity and augmenting upper-body strength, an area that still bears a lot of uncertainty.”

“Ideally, I’d like to lend mobility to those unable to walk at an equal scale to those who can,” she said. “My research is also focused on dexterity and augmenting upper-body strength, an area that still bears a lot of uncertainty.”

The prospect of one day being called Dr. Huynh doesn’t faze her: “Me, this kid who was never great at math, who didn’t even know what an engineer was until freshman year of college, some nobody kid from Cowtown, New Mexico — come on!”

She visits Belen every so often, driving past the ghosts of her childhood, the old barn hardly standing, the old shop begging for work.

“The bones of my dogs are still in that ground, the bones of my horses. This is where I learned to work on cars and learned to spit proper,” Huynh said.

Belen is where it all began, her search for iron will and iron purpose.

Not surprisingly, it was never too far.