A little boy of 5 is wheeled into a room at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Although accompanied by his mother and father, he feels scared.

And for good reason. The child, a cancer patient, has been through this before. He’s about to have an IV before a 90-minute MRI. A child life specialist joins the family and asks the boy how he’s doing, his name, age and where he goes to school. She smiles kindly but barely allays the boy’s fears.

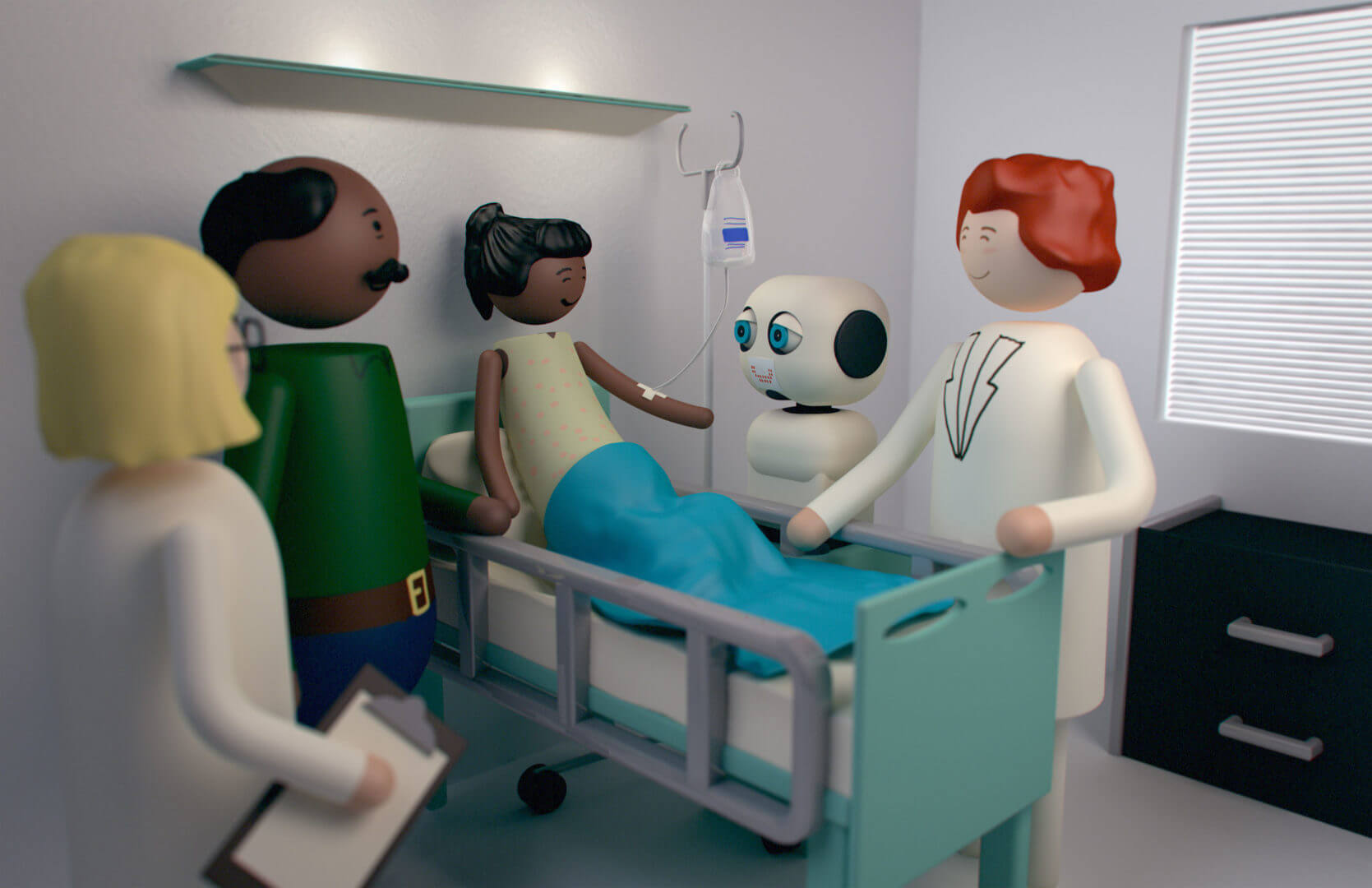

Then she introduces a special guest she has brought along. Suddenly the boy smiles. At the foot of his bed, a friendly visitor — short and adorable beneath a surgeon’s cap — materializes. “Hi, my name is Ivey, and I’m here today to talk to you about your IV,” Ivey says in a childlike voice. “We’ll get through this together.”

The guest isn’t a physician’s assistant, nurse or even a healthcare worker. Ivey is a robot, one that researchers at USC Viterbi and CHLA believe could one day alleviate fear and anxiety in children about to undergo a painful medical procedure such as an IV.

“The robot is meant to be a peer, an experienced buddy that complements doctors, parents and specialists,” said USC Viterbi Professor Maja Matarić, project leader and founding director of the USC Center for Robotics and Embedded Systems. “Wouldn’t it be great if we could use this technology, which is very relatable to children, to improve the quality of care?”

Overstressed children sometimes wiggle around and dislodge their IVs, said Margaret Trost, a CHLA pediatric hospitalist and project co-leader. In addition to wasting time and resources and heightening parental anxiety, this causes young patients more discomfort with the administration of a new IV.

“Until now, there hasn’t been enough emphasis about making medicine hurt children less and cause them less distress,” Trost said.

The interdisciplinary USC Viterbi-CHLA research team wants to change that by employing specially programmed Maki robots to interact with children ages 5 to 10. Although the research is still in the preliminary stages, early results have proved promising.

As envisioned, the one-foot tall robots, built with a 3-D printer, would “converse” and empathize with kids, as well as engage them with tablet-based games. All robotic interactions would be customized to ensure the best possible care. Here’s how it works.

As a child waits to receive a needle stick for an IV line or another painful medical procedure, a child life specialist would roll a cart that holds the robot, a Kinect 2 device and a hidden computer into the room.

The child would be asked to choose one of five faces on a tablet that best expresses her anxiety level, ranging from smiling to crying. Throughout the entire process, the Kinect would capture the child’s facial expressions to detect changes in stress levels, allowing computer algorithms to modify the interaction at any time.

Say the youngster selects a smiling face and tells the child life specialist that she feels brave. The robot would praise the child’s courage. However, if during the interaction her pulse suddenly speeds up and the Kinect detects signs of increased stress, the robot might tell the child that it understands how she feels and suggest some breathing exercises or choose a tablet-based game to play, said Jillian Greczek, a USC Viterbi Ph.D. student in Matarić’s lab who oversees the project and whose research deals with helping people cope with chronic health conditions.

“We have evidence from previous studies that socially assistive robots can help children by augmenting existing infrastructure,” Greczek said. “And in this study, the robot is a helpful, intelligent agent working with the child life specialist to reduce child anxiety.”

The robot-child communication can be as long or short as necessary. If a nurse appears to administer an IV, for instance, the child life specialist or doctor could quickly shut off the robot — but not before the robot says goodbye.

For more than a decade, Matarić — the Chan Soon-Shiong Professor of Computer Science, Neuroscience and Pediatrics — and her research team have studied ways in which robots might provide one-to-one personalized care to assist various populations, including people with Alzheimer’s disease, stroke patients and children with autism.

The field of socially assistive robotics, defined about a decade ago by Matarić and her former graduate student, David Feil-Seifer, has won widespread recognition. In 2009, Matarić received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics & Engineering Mentoring.

She believes the program using robots to reduce children’s anxieties in medical settings holds great promise.

“As we gain insights into the way socially assistive robots interact with children in real-world settings and help them to be less stressed, I think we can generalize the lessons learned to help other populations as well,” Matarić said.